|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

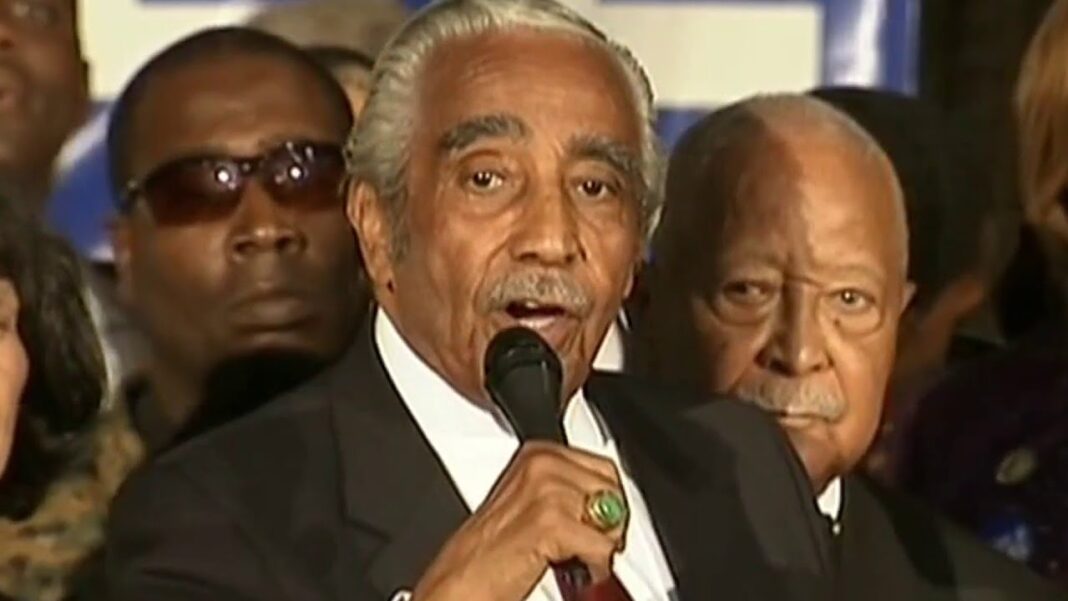

Charles B. Rangel, Towering Harlem Lawmaker and House Ways and Means Chairman, Dies at 94

By: Jerome Brookshire

Charles B. Rangel, the indomitable congressman who reshaped Harlem’s political landscape and broke racial barriers on Capitol Hill before a late-career ethics scandal dimmed his legacy, died on Monday in Manhattan at the age of 94. His family confirmed the news, and Lloyd Williams, president of the Greater Harlem Chamber of Commerce and a longtime confidant, told The New York Times that Rangel passed away at Harlem Hospital on 135th Street and Malcolm X Boulevard — mere blocks from where he was born and spent nearly his entire life.

“Charlie was born on 132nd Street between Lenox and Fifth, and when he became successful, he moved to 135th Street between Lenox and Fifth,” Williams said. “He used to joke about moving up — three blocks.”

A lion of Harlem’s storied Democratic establishment, Rangel represented New York’s 13th Congressional District — a seat rooted in Black political power — for 46 years, making him the second-longest-serving member of Congress from New York after Emanuel Celler. According to The New York Times report, Rangel’s tenure spanned generations of social transformation and racial reckoning in America, and he stood at the center of it all — a fixture in Washington politics and Harlem’s local pride.

Rangel first burst onto the national stage in 1970, when he defeated the legendary Adam Clayton Powell Jr., a charismatic but scandal-marred civil rights pioneer who had become politically vulnerable. The upset victory marked a changing of the guard and signaled the rise of a new generation of disciplined, pragmatic Black leadership, one less flamboyant than Powell’s but arguably more enduring.

From the start, Rangel was a consensus builder, blending street-smart politics with a genteel air that belied his tough upbringing and combat experience in Korea. “I’m a successful politician who more than happens to be Black,” Rangel famously said — a testament to the scope of his ambition and his refusal to be defined solely by identity politics.

In 1974, just four years into his congressional career, Rangel made history as the first African American appointed to the influential House Ways and Means Committee, the body that oversees taxation, trade, Social Security, and Medicare. His ascendancy was slow but steady, and in 2006 — after decades of Democratic minority status — he claimed the panel’s chairmanship when the party retook the House.

As The New York Times reported, his tenure was marked by significant clout over national fiscal policy, yet it ended in humiliation after an ethics investigation found he had accepted corporate-sponsored trips to the Caribbean in violation of congressional gift rules.

On December 2, 2010, Rangel — then 80 years old — stood alone in the well of the House as Speaker Nancy Pelosi administered the formal censure, a historic rebuke passed by a vote of 333 to 79. He was only the 23rd member of the House to be censured and the first in nearly three decades. Despite the gravity of the moment, Rangel’s deep reservoir of constituent goodwill remained intact. Just a month earlier, as The New York Times report noted, voters had overwhelmingly re-elected him — a reflection of Harlem’s fierce loyalty to its elder statesman.

He formally relinquished the Ways and Means gavel in early 2010 but refused to retire, securing re-election one last time in 2014 before stepping down in 2016 after a bruising battle with rising Dominican-American political star Adriano Espaillat.

Rangel’s departure marked the end of an era. He was the last living member of the “Gang of Four” — a tight-knit group of Harlem powerbrokers that included David Dinkins, New York’s first Black mayor; Percy Sutton, former Manhattan Borough President; and Basil Paterson, father of future Governor David Paterson. Together, they formed the backbone of Black political advancement in the city throughout the late 20th century.

But Harlem — and its demographics — had changed. By the time Espaillat succeeded Rangel, the 13th District had shifted northward, encompassing Washington Heights and a burgeoning Dominican population. Rangel’s 2012 and 2014 primary battles revealed the limitations of old-guard loyalty in the face of demographic realignment.

Still, The New York Times report observed that while political rivals accused Rangel of being out of touch or clinging to power, few ever doubted his charm, intellect, or commitment to his constituents. Known for his elegant mustache, gravelly voice, and impish grin, Rangel was a gregarious figure on the Hill — “Mr. Conviviality,” colleagues might have called him had there been a congressional yearbook.

Though he once made a brief, unsuccessful bid for citywide office in 1969, Rangel’s heart never left Harlem. His constituents affectionately called him “Charlie,” and he viewed public service not as a stepping stone, but as a calling.

Despite the stain of censure, Rangel’s record of legislative accomplishment — especially in the realms of economic development, anti-drug trafficking measures, and international trade — cemented his reputation as one of the most influential African American lawmakers in U.S. history. He played key roles in drafting the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit and the Empowerment Zone tax incentives, both credited with spurring investment in urban communities like his own.

As The New York Times report noted in its extensive coverage of his career, Rangel also wielded behind-the-scenes influence in Democratic Party politics. In 2000, he was pivotal in persuading Hillary Clinton to run for U.S. Senate from New York, an entry that would define her national political trajectory.

Rangel’s death prompted tributes across the political spectrum. In Harlem, he is remembered not merely as a politician, but as a son of the neighborhood — one who survived the Korean War, fought for civil rights, and built bridges between Washington and 125th Street.

His life’s journey — from poverty to power, from foot soldier in Korea to chairman of the most powerful committee in Congress — was quintessentially American, and distinctly Harlem. As The New York Times editorialized in 2016 upon his retirement, “Few lawmakers have done more to give voice to a community and, in doing so, reshape the conversation about race, power, and politics in America.”

Charles Bernard Rangel is gone, but the echoes of his gravelly voice and indomitable spirit remain — in Harlem, in Washington, and in the arc of American political history he helped bend.

May his memory be for a blessing.