Musician and scholar transcribed and recorded historic ‘nigunim’

Song has always been at the heart of Chassidic life and practice. Nigunim, usually wordless melodies, have long held a central place in prayer, study and gatherings. Many are considered acts of Divine musical inspiration, with some of the most uplifting works composed by founders of the movement, including the Baal Shem Tov, Rabbi Yechiel Michel Zlotchever and Rabbi Levi Yitzchok Berditchever, as well as by their successors.

Famously, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of the Chabad movement, himself a preeminent composer of nigunim, declared that “the song is the pen of the soul” and at times answered practical questions posed to him with wordless melodies. Songs served not only in the avodah, the Divine service of a Chassid, but also formed a sort of cultural currency as they were taught at communal gatherings and traded between Chassidic groups across Europe.

By the mid-20th century, more than 200 years of musical tradition was in danger of being lost. Judaism in Eastern Europe had gone up in flames during the Holocaust or was suppressed during decades of Soviet repression, and most survivors were either trapped behind the Iron Curtain, or faced the assimilation and indifference of life in America and the West.

Velvel Pasternak, who passed away on June 11 at the age of 85, played a critical role in recording and transcribing these tunes, preserving them for future generations.

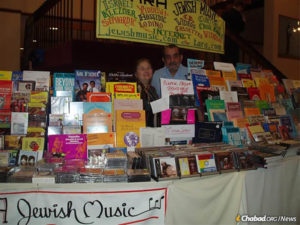

During his lifetime, he recorded hundreds of Chassidic melodies from Lubavitch, Modzitz, Bobov, Ger and other Chassidic courts, as well as Sephardic melodies and more modern Israeli ones. Recorder and notebook in hand, he traversed the United States and Israel to document these songs.

Through Tara Publications, the imprint he established (named for his daughter, Atara), he published dozens of compilations of Jewish songs. Key to his work was the deep respect in which he held communities whose music he recorded. Pasternak was born in Toronto in 1933 to immigrant parents from Poland. As a child, he relished the nigunim he heard at the Modzitzer shtiebel where his family prayed. His mother, seeing her son’s gift for music, decided to buy him a piano. An autodidact, Pasternak taught himself to play piano, later learning music theory from a lonely scholar. The fee for these lessons? Keeping his teacher company at a local bar once a week.

Though he initially planned on becoming a pulpit rabbi after graduating from Yeshiva University, Pasternak was drawn to pursue a master’s degree in music education from Columbia University.

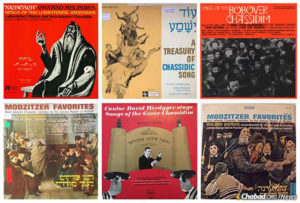

In 1960, Pasternak was approached by Benedict Stambler, a collector of Jewish music and the head of Collectors Record Guild label, to arrange and conduct a chorus of Lubavitcher Chassidim in what was to be the first recording of Chassidic songs actually sung by Chassidim. This record was the first of what ultimately would be a 16-part series comprising the main corpus of Niggunei Chassidei Chabad, known as Nichoach.

First, the ‘Farbrengen’

The preservation of Chassidic music was a longstanding tradition in Chabad. In Russia, the fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Sholom Dovber of Lubavitch, expressed an interest in teaching nigunim in a more organized fashion. Starting from Simchat Torah in 1899, the singing and teaching of nigunim became part of the regular curriculum at the Tomchei Temimim network of Chabad yeshivahs.

Following his expulsion from the Soviet Union, the Sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—made a concerted effort to preserve Chabad nigunim that were at risk of being lost and forgotten in the Soviet Union, where singing Jewish songs could lead to imprisonment, even death. In 1935, he contacted Chassidim still in the USSR, asking them to undertake the dangerous task of traveling to pockets of the Chassidic underground and transcribing the songs they heard. This act was also groundbreaking since traditionally many Chassidim were concerned that the act of transcribing and recording the songs could rob them of the intangible spiritual nuances that could only be conveyed by hearing them directly.

In 1944, Niggunei Chassidei Chabad (Nichoach) was formed at the previous Rebbe’s behest under the auspices of Rabbi Shmuel Zalmanov, with the express intent of transcribing and cataloging all known Chabad nigunim, so that they later could be recorded with a choir and registered with the proper copyright.

Zalmanov ultimately documented 347 songs, published by Kehot in the Sefer Hanigunim set. In 1957, following the success of the initial volume of Sefer Hanigunim, the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of righteous memory—suggested Nichoach begin recording the songs.

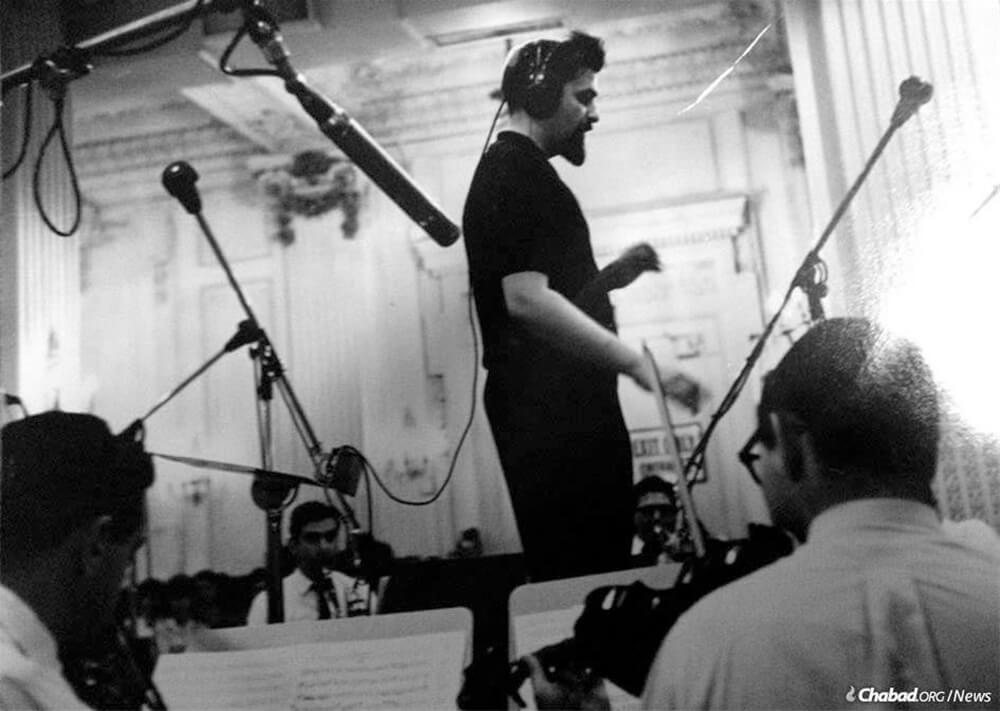

Zalmanov pulled together a group of cantors and venerable Chassidic singers, and contacted Stambler, who in turn roped in Pasternak. Meeting in a basement in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., Pasternak was introduced to his “hand-picked chorus” of Chassidim. Almost immediately, the young conductor realized that he had considerable work cut out for him shaping them into a recording-ready choir. Even the question of how to start and end each song was in doubt. The Chassidim, accustomed to singing as a convivial but chaotic crew at farbrengens, felt assured they could all keep time with each other. Pasternak, on the other hand, knew that without careful precision and practice, the recordings would be unusable.

After six months of practice, Pasternak felt they were ready to record. With the studio booked and the appointed hour approaching, the Chassidim had yet to arrive. Finally, five minutes before recording was to begin, a gaggle of some 60 Chassidim entered the room.

In addition to the singers, elderly men, women and children—all well beyond the 24-member chorus and band—packed into the recording studio to show their support. With them were cases of soda, sponge cake and four bottles of l’chaim (of the variety known colloquially as zeks un ninetziger). At the rate of $45 per hour, any delays in the recording studio would be costly, but the Chassidic choir was firm in their plans.

They informed Pasternak that they would be holding a farbrengen in order to prepare themselves for the spiritual task ahead of singing.

“How long will this farbrengen last?” Pasternak asked.

“This farbrengen will last as long as it lasts,” was the answer, “and not one minute longer.”

When it had concluded, Zalmanov approached Pasternak with one final request.

“It’s a small favor,” he said “ but please don’t conduct.”

“Please what?” Pastnernak recalled responding. “What do you mean, ‘Don’t conduct?’ ”

Pasternak would have none of it. After six months of preparation, he had one job, and he was surely going to do it.

“I will tell you the truth,” said Zalmanov. “You can make with the hands, but nobody will watch you. Because if they watch you, it will get in the way of their kavanah, their concentration.”

Indeed, as Pasternak began to conduct, the 16-member Chassidic chorus shut their eyes in concentration and began to sing.

“I could have been in another state as far as my singers were concerned,” Pasternak later quipped. “But to the credit of the Lubavitch Chassidim, they were right, and I was wrong. They were handpicked Chassidim, instructed to present to the world the first recorded music of Lubavitch at the bidding of the Rebbe. As such, they treated the project with much more religious conviction and feeling than I had.“

The resulting record, the first in ultimately 16 albums of Chabad Chassidic nigunim, was met by surprising success. The London Jewish Chronicle proclaimed it to be “the finest recordings of authentic Jewish music ever made.” Famed conductor Leonard Bernstein even used one of the selections from the record for a program of religious folk music.

Pasternak continued to produce Jewish albums and songbooks, including the acclaimed Songs of the Chassidim series. His collections of Sephardic melodies included Ladino tunes and music that spanned communities from Bosnia to Calcutta. Many of his books became standard in the repertoire of any aspiring Jewish music student, opening a world of Jewish music beyond “Dayenu” and “Hava Nagila.”

Velvel Pasternak is survived by his wife, Goldie; five children; and 22 grandchildren.