|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Matzot and the Soviet Jewry Movement

The struggle for the procurement of Matzot for Passover for the beleaguered Jews of the Soviet Union was connected to the Soviet Jewish struggle for religious freedom.

As Passover was approaching, an announcement made in the Moscow Central Synagogue on March 16, 1963, that state run bakeries would not provide Matzot caused great disappointment. A year earlier, the Soviet government officially prohibited the distribution of matzot throughout the Soviet Union. In response, Jews around the world began to raise their voices in protest.

On April 12, 1962, a few hundred Jewish students from various New York colleges marched silently for two hours in front of the Soviet UN Mission in Manhattan in protest against the ban.” In their released statement, they called the Soviet prohibition part of a “larger official attempt to destroy the bond between Soviet Jewry and the traditional roots of Judaism which have a national historical significance.” This was one of the first protests ushering in the era of the Soviet Jewry movement. The following year, as Passover holiday approached, a flurry of activity would follow.

On March 20, 1963, US Senator from New York, Jacob Javitz, sent an appeal to the Soviet ambassador to the United States, Anatoly Dobrynin to intercede in allowing shipments of American baked Matzot. Several American Matzo manufacturers offered to send abundant amounts of Matzot to Soviet Jews.

One week later, the preliminary stage of a resolution was passed in Congress to use US facilities to send Matzot to Soviet Jews.

At the same time, following the opening session of their biennial conference, delegates from the World Conference of Jewish Organizations issued a “most earnest appeal” to the Soviet Union to allow the baking of Matzo.

That year, the Soviets did not comply with efforts to persuade them.

By 1964, feeling some pressure, the Soviets appeared to express willingness to make some concessions. A month before Passover, Soviet diplomats abroad responded to Jewish religious leaders’ inquiries on the matter of matzo.

In Washington DC, on February 7, Genardy Gavrikov, a Secretary of the Soviet Embassy in Washington stated that Jews in the USSR would be entitled to bake Matzot after a meeting with Rabbi David Hill, president of the Young Israel organization.

One month later, during a two hour visit to Jerusalem’s Heichal Shlomo Synagogue, the Soviet ambassador to Israel, Mikhail Bodrov, (Israel and the USSR had diplomatic relations until the Six Day War) wearing a kippa on his head, said he would look into the matter of the refusal of Soviet authorities to allow the import of Matzot for Passover.

On March 18, a resolution by Congress called upon President Lyndon Johnson “to use the full facilities of our Government” to make sure adequate supplies to Matzot reach Soviet Jews.

Later that week, week, on March 24, the New York Board of Rabbis representing the Orthodox, Conservative and Reform, appealed to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights requesting that Jews be allowed to bake and import Matzot.

Would home baking of Matzot indeed be permitted? Could it suffice? Private homes were inadequate for baking and supplying sufficient quantities. At the same time, there were additional arrests and incarcerations of individuals who were found baking matzot. The outcry from voices in the West intensified.

Would the Soviets permit Matzot on Passover?

The Chief Rabbi of England, Rabbi Israel Brodie, appealed to Soviet authorities “in the name of Anglo-Jewry” to permit Jews to have matzot for upcoming holiday. He appealed to Soviet authorities “to permit the basic religious requirement to be performed in an adequate and satisfactory manner.”

That Passover, a special prayer was added to the seder by Rabbi Brodie, articulating the increasing identification of World Jewry with the plight of their brethren. “Behold this Matzo, the symbol of our affliction but also of our liberty. On this festival may our hearts be turned to our brothers and sisters in Russia who were not permitted to bake Matzo and to celebrate this Passover.”

The World association Jewish Students appealed to the UN Commission of Human Rights to intervene for the release of Jews arrested the previous week for baking Maztot.” Their message also protested the ban on Matzot.

As Passover approached, twelve major American Jewish organizations expressed readiness to send a planeload of Matzot. They urgently requested the consent of the Soviet government to approve this undertaking. The Soviets did not concede.

As Passover began on April 8, a story appeared in Jewish Telegraphic Agency on April 10, that the Moscow Central Synagogue was crowded with worshippers, but “few were in a position to secure Matzot.”

The efforts did not produce change. The Soviet response seemed once again to be ‘Nyet!’But Jewish activists sought results. With the arrival of 1964, as the outcry grew, the Soviets did show some signs of yielding. Just prior to Passover in 1964, the Moscow Jewish community was permitted to rent a small bakery to bake matzot. By 1965, concessions increased, as some synagogues in major cities were also permitted to be used for baking matzot. Jews were also allowed to receive individual packages of over ten thousand pounds of matzot sent from abroad. By 1966, bans were lifted in some capitals of the Soviet republics, and in the regions within the Soviet Southern republics that possessed Jewish communities.

The pressure intensified as the Soviet Jewry movement grew worldwide.

Over the next few years, the Soviets eased more restrictions and matzot were more readily available.

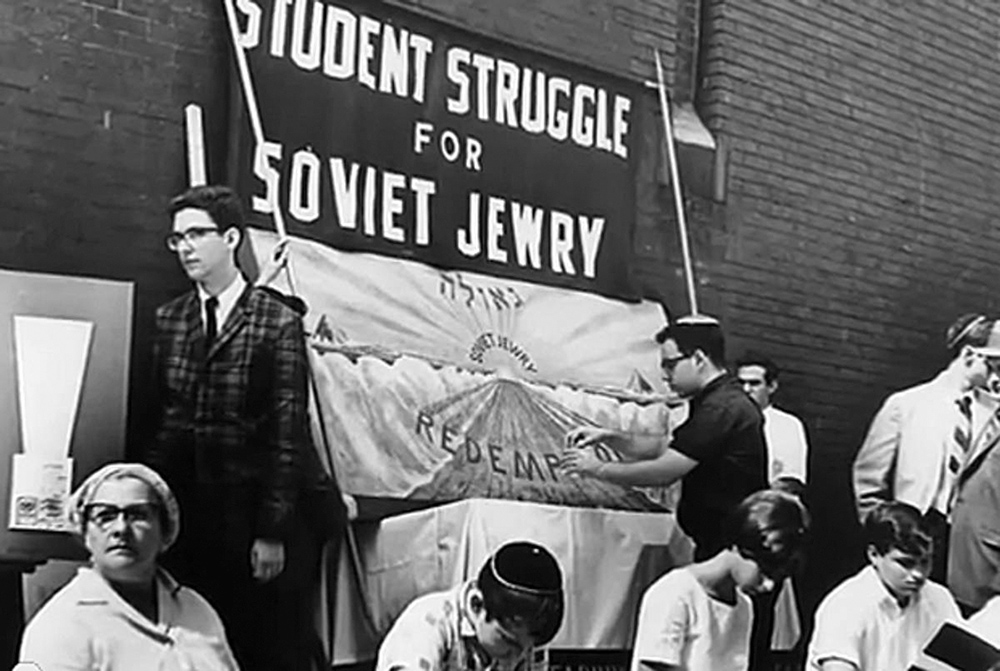

Glenn Richter, one of the founders of the activist Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry in 1964, relates, “We had the definite feeling that there was an effective ban by the Kremlin producing sufficient Matza and what little occurred was largely for show to the West. We well remember the effective ban the previous year, 1963, and that certainly pushed our actions a year later.”

The Soviet Jewish drive and persistence to fulfill the obligation of partaking of Matzah on Passover and the success of endeavors to provide Matzot occupies a special place in the history of Soviet Jewry.