|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Local leader uncovers new evidence of massacre

By: Menachem Posner

In 1921, the entire Jewish community in Mongolia was brutally massacred. For a century, no one knew where they were buried. Until now.

This is the story of an antisemitic warlord, a brutal purge, and a tiny pocket of Jewish life in one of the least expected places on earth.

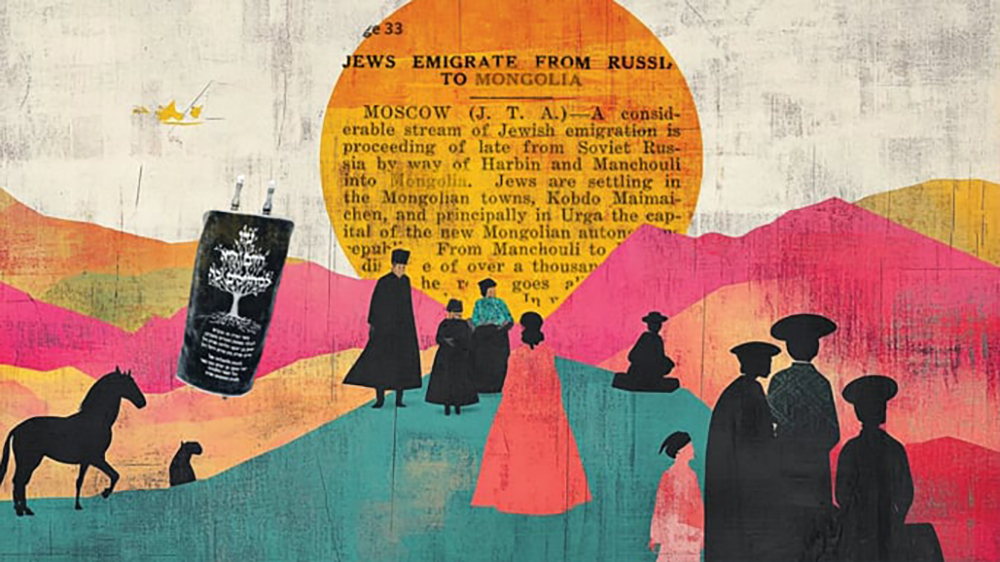

Jewish Life in Mongolia

If one were to choose a word to describe Jewish life in Mongolia today, it would be “scant.”

There is no synagogue, no Jewish community center, and no formal infrastructure to support the handful of Jews scattered across the landlocked nation. Yet Israeli-born businessman Yair Jacob Porat, who lives in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar, has taken responsibility for Jewish life in the region. Since moving to Mongolia in 1996, Porat has hosted Shabbat dinners, imported kosher staples, and organized holiday celebrations, often with the help of Rabbi Aharon Wagner, Chabad emissary to Irkutsk, Russia.

Porat counts the local Jewish community in the single digits: three Israelis married to locals, a few expats from the United States and England, and an occasional Jewish tourist passing through. Despite the small numbers, he ensures that everyone, no matter where they’re from, can celebrate Judaism. This includes holding a local Megillah reading (with a scroll he purchased) and giving out matzah and wine before leaving to Israel to spend Passover with family.

His apartment doubles as a makeshift synagogue, complete with prayer books and other supplies, and, as of this spring, a Torah scroll—the first to arrive in Mongolia in living memory. But there is rarely a minyan, the required quorum of 10 Jewish males needed to hold a Torah reading.

A Community Erased

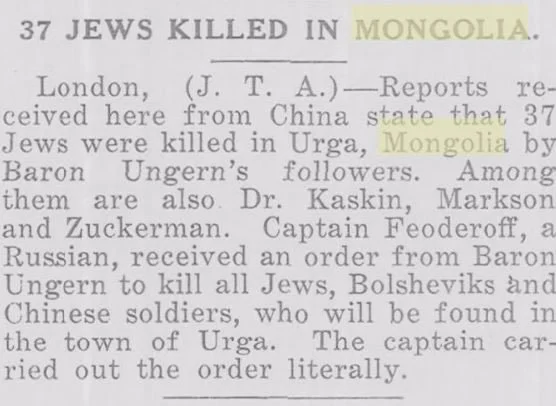

As the de-facto person responsible for Jewish life in the landlocked nation, Porat also feels a sense of responsibility toward the Jewish people who lived in Mongolia 100 years ago and were massacred in June 1921. According to the J.T.A., the mass murder was carried out by a certain Captain Feodoroff at the orders of the notorious Baron Ungern, who instructed his followers to kill “all Jews, Bolsheviks and Chinese soldiers.”

Ungern was an anti-communist general in the Russian Civil War and then an independent warlord who aspired to restore the Russian monarchy after the 1917 Russian Revolution. Suspecting the Jews of harboring pro-communist leanings, he ordered them all killed, regardless of age, political activity or station.

One of the very few to survive the massacre was a Jewish man, Baron Alexander Zanzer, who had succeeded in integrating into local society to the point that he was conferred a noble title and a Mongolian name honoring Öndör Gegeen Zanabazar by Bogd Khan.

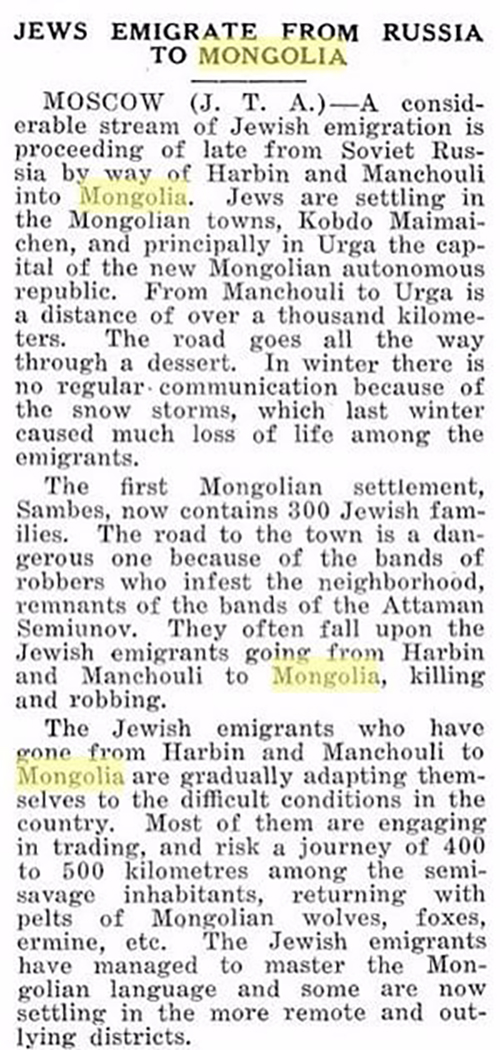

Despite the bloody end of the local Jewish community, it took just a few short years for hundreds of Russian Jews to stream back into Mongolia, attracted by the opportunity to trade in oil, cigarettes, pelts, and other commodities.

Their numbers were bolstered during the Holocaust when Soviet authorities relocated several thousand Lithuanian Jews to farms in Soviet Mongolia and Eastern Siberia before the German invasion, according to a J.T.A. report from September 17, 1941.

But decades of Communist rule left their mark and the fledgling Jewish community faded into oblivion.

The Search for Forgotten Graves

As the only practicing Jew in Mongolia, Porat says he has long wondered “why there is no Jewish center in Mongolia or Jewish presence at all.” In contrast, he points out, there are Jews in China, Russia, and other neighboring countries.

As he learned more about the bloody past, he felt compelled to locate the graves of the victims of the massacre and pay honor to their souls.

His search led him to libraries and government archives, where he was met with dead end after dead end. But speaking to elderly government officials and monks led him to the Russian church, which was apparently keeping some confidential information.

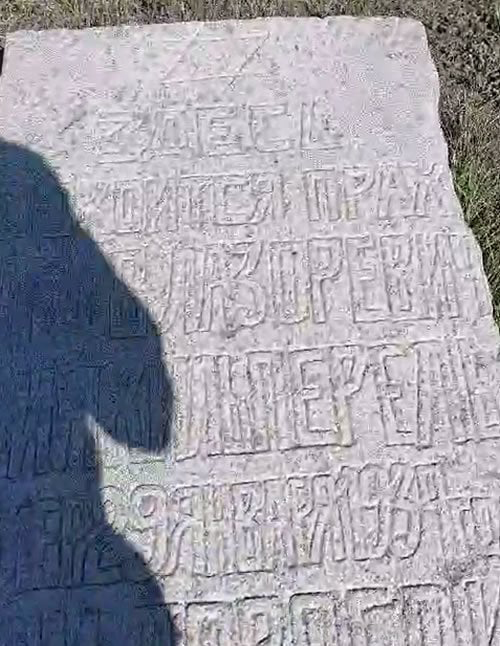

Through the efforts of a Russian journalist, he was introduced to the head of the Russian church, who revealed that in the Russian-Orthodox cemetery in Ulaanbaatar, some graves are marked with Stars of David as well as some Jewish names.

Together with a local guide, Porat spent two hours rooting around in the overgrown cemetery. Finally, he found what he believes to be the mass grave of the victims of the purge—an area behind the Communist-era monument to the heroes of the “Great Patriotic War.”

The plot has long been neglected and it is clear that many of the early-20th-century markers are no longer extant. One can, however, see a grave with a Jewish name from 1965 and another with a Star of David from 1937, bearing silent testimony to a community that has virtually vanished into anonymity.

And then there are the mass graves.

One low-lying monument is simply engraved with a large Star of David, the number 15, and the letter M, signifying that 15 men were buried there together. Not far away, a large star lies sunken into the ground, with few clues as to what it may signify or who may lie underneath.

In November 2024, Porat visited the cemetery once more. He lit a candle and recited Psalms for the souls of those buried there.

What Lies Ahead

After speaking to the cemetery guards, he has determined that fencing off the Jewish part of the cemetery is feasible. The ground is now frozen, however, so that will need to wait until spring.

Porat says he was inspired to undertake the project by Rabbi Osher Litzman of Chabad of Korea, whom he visited not long ago. When Rabbi Litzman heard about his discovery, he shared a story about a similar cemetery in Munich, where many victims of the Holocaust had been laid to rest. The cemetery’s wall had crumbled to the point where it was no longer distinguished from the non-Jewish burial ground surrounding it. The Rebbe sent an urgent message to Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Glick of London, urging him to rectify the situation and fence off the Jewish cemetery, which he did post haste.

While Porat has visited the cemetery several times, the living Jews are his primary focus. Through social media and close coordination with the Chabad emissaries in the Far East, he extends an open invitation to tourists to join him for Shabbat and hopes that the country will one day have a Chabad center of its own.