|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Dovid Zaklikowski

During World War II, the center of world Jewry in Europe was in the midst of being destroyed. Mass murder by the Germans was the norm, targeted against Jews of all backgrounds and nationalities, who were executed on the streets and gassed in concentration camps.

Jewish life and tradition were on the brink of annihilation. But as they tried to escape, the Holocaust’s victims faced the doors of the world slammed shut. Immigration quotas filled up quickly, and the global community of nations expressed little interest in helping the masses of European Jews find refuge.

Miraculously, the Sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory, made it to the United States in March 1940, along with a few family members and several aides. From his new home in New York, the Sixth Rebbe tried in vain to procure documents and information to save those he knew were trapped back in Europe, but as they were Polish citizens and Poland would not grant them exit visas, the State Department refused to intervene on their behalf. In the conflagration of World War II, the Sixth Rebbe was unsuccessful even with his own daughter and son-in-law, Rabbi Menachem and Shaina Horenstein, who lived in Otwock on the outskirts of Warsaw and perished in Treblinka.

But his middle daughter and her husband – the future Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, and Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka Schneerson, of righteous memory –were born in Russia and thus had a small chance of escape from France.

With the assistance of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, known as HIAS, the Sixth Rebbe learned that because the Russians were forbidding their Jews from leaving, there was no one to fill the Russian immigrant quotas in the United States. At first the sixth Rebbe wanted the application for the visas to state that his son-in-law would be a part of the hierarchy of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, but HIAS advised that it would be best for his son-in-law to as an engineer, as he had studied engineering at several universities in Paris.

The future Rebbe and Rebbetzin arrived at Pier 8 in Staten Island, N.Y., on the 28th day of the Hebrew month Sivan, a date celebrated by Jewish communities around the world as heralding the educational revolution that the future Rebbe would lead.

Chabad Roots in the United States

The Sixth Rebbe and his son-in-law were met with an American melting pot that had consumed hordes of European Jews with the lure of secularism, the challenges of earning a livelihood, and the lack of Jewish infrastructure.

The environment hadn’t changed since the Sixth Rebbe journeyed throughout the United States in 1929, travelling to major cities with sizable Jewish communities, including Baltimore, Md., Detroit, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, St. Louis, Mo., and Chicago.

Wherever he went, thousands gathered to hear his heartfelt talks. The Sixth Rebbe beseeched his audiences to strengthen their observance of Judaism, and coordinated the establishment of women’s groups to build ritual baths, and committees to organize classes on the Talmud, Jewish law and Chabad philosophy.

Upon the Sixth Rebbe’s departure for Eastern Europe at the end of his visit, groups established their own committees to convince their leader to establish his headquarters in the United States. In heartfelt letters, the Rebbe responded that at the present time, his most important mission was to help Jews in the Soviet Union and in Europe. The Rebbe did not end there, and implored his correspondents to fulfill their own duty in bolstering Judaism in their own country.

Still, when he returned to Europe, he told Chabad luminary and scholar Rabbi Yochanan Gordon during a private audience to move overseas.

“Your brothers in the United States tell me that they want you to come there and that you don’t want to,” the Sixth Rebbe told Gordon.

But Gordon, whose brother immigrated and lost his children to secularism, wanted to shield his own children from such a fate.

“I do not want my children to follow in this way,” Gordon responded. He wanted his children to learn in Lubavitch schools.

“Don’t worry about their future,” the Sixth Rebbe told him, ensuring that even in the United States, they would learn in Lubavitch schools.

When the last of the Gordon family arrived in the United States in the early 1930s, no one believed that there would ever be a Lubavitch school in the United States. And then the Sixth Rebbe permanently moved to New York in order to assist the Jews in Europe and build educational institutions in the United States.

Escaping With Pen in Hand

While his father-in-law did all he could to secure the future Rebbe and Rebbetzin’s secure passage to America, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, who at the time was known by his acronym, the Ramash, faced a Paris in upheaval. The few months of quiet gave way to Germany’s June 5, 1940 invasion of the 400-mile stretch of land between Abbeville and the Upper Rhine. By June 14, a swastika could be seen atop Eiffel Tower.

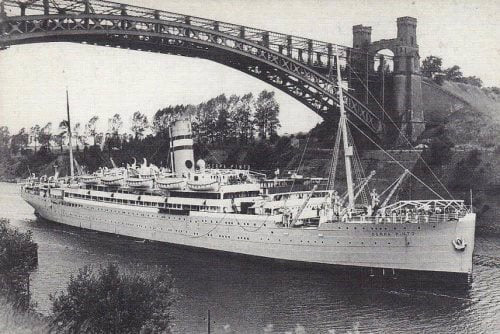

Two days before the occupation of Paris, the future Rebbe and Rebbetzin fled for Vichy. From there, they went to Nice and on to Marseille. From there they fled from France and on to Lisbon, Portugal, where they boarded the S.S. Serpa Pinto for the New World.

While fleeing, most passengers carried a suitcase or two, but the Ramash through all his travels and the turmoil took many cases of scholarly books and manuscripts written by Chabad-Lubavitch leaders, many of them passed down from each Rebbe to the next.

Amongst the items he brought were notes of the Ramash’s many public talks on the weekly Torah portion and classes on the Talmud. Many of the teachings, which the future Rebbe would continue to commit to writing for the remainder of his life, comprised deep analytic interpretations of a specific source text that would then flow into the Kabbalistic and Chasidic lessons which he distilled so that everyone could apply those teachings to their daily lives.

“Little is known about the Rebbe’s stay in Portugal,” states the website of the local Jewish community, Comunidade Israelita de Lisboa, that to this day celebrates the fact that the Ramash stopped there on his way to the United States. “What is known is that in the collection of the writings of the Rebbe, there are notes from a lecture in a local synagogue, written during his stay in Portugal on a very obscure text from the Talmud.”

The Rebbe once analyzed a puzzling Talmudic expression about finding a fish for a sick person, basing his analysis on other Talmudic sources and many commentaries before framing the discussion according to the teachings of Kabbalah. He described a fish’s life as a metaphor for Jewish existence.

Fish survive because they know their environment and they remain immersed in it, the Rebbe wrote. If you see a fish flailing on the dock, its prognosis is instantaneous and universal.

The same can be said for the Jewish people, he concluded. A Jew has his own environment and source of spiritual nourishment: the Torah. Like the sick person in the Talmud, a Jew sometimes tries to live “out of the water,” and unlike the fish, his source of vitality isn’t always apparent to all. The key for the Jew is to recognize his source of life.

From Manuscripts to Books

A year after they fled Paris, a more than 10-day journey took the future Rebbe and Rebbetzin to the United States. The Sixth Rebbe, pointing to his son-in-law’s scholarly knowledge, instructed the students and faculty of the new Lubavitch yeshiva in Brooklyn to go to the pier to greet him, sending them a message, “My son-in-law is fluent in the entire Talmud, many commentaries and all published volumes of Chasidic teachings.”

Upon his arrival, the small Chabad community requested that the Ramash lead a Chasidic gathering. Characteristic of his shying away from public recognition, he reluctantly accepted. The gathering would be in order to thank G‑d for being saved from the European inferno.

“He was very slim, he wore a gray jacket and grey hat,” remembered Rabbi Yisroel Gordon, who was a little child at the time. “And a short while later he began to work from 11 in the morning to 4:30 at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.”

At first, locals could only sneak a glimpse of the Ramash’s greatness during the Sabbath.

“I saw the way he prayed, and his kind, personable and refined personality made a great impression on me,” recalled Gordon.

“The Rebbe refused to lead Chasidic gatherings at the synagogue,” said Rabbi Yehudah Leib Posner, a young student at the time. “He said that the synagogue was where the school was and he was not in charge of the activities in the school, that they should rather invite the one in charge of the school to lead the gatherings.”

But locals, including the synagogue’s beadle, Meir Roth, complained that they had trouble understanding the school’s director. Roth appealed to the Sixth Rebbe.

“The Rebbe gave him three dollars and instructed him to relay to his son-in-law that by his contribution, he himself was taking part in the gathering,” said Posner. “Only then, would he join.”

“Those gatherings were a scholarly feast,” said Rabbi Tzvi Hirsh Fogelman, a student at the time and later the director of Chabad-Lubavitch of Worcester, Mass. “While at other times, [the future Rebbe] tried to hide from everyone that he was anything special, since the gatherings were a directive from the Sixth Rebbe, he had no choice but to transmit a taste his vast knowledge in all the various parts of Torah scholarship.”

“Those gatherings made a great impression on us,” said Gordon. “We felt he understood the Americans, he was sincere in what he said, and that whatever he asked of us he asked much more of himself.”

The Sixth Rebbe directed his son-in-law to lead the educational, social service and publishing arms of Chabad-Lubavitch, some established by him upon his son-in-law’s arrival. Among his other appointments, he was also chosen to lead the community’s burial society and serve as vice president of Agudas Chasidei Chabad, the umbrella organization of Chabad-Lubavitch presided over by his father-in-law.

“When the Ramash arrived in New York, there was an upswing in activities, especially in the extra-curricular educational activities for kids,” reported Fogelman.

As director of the Lubavitch publishing house and with most of the Chabad leaders’ manuscripts stuck in Poland – left behind for safekeeping in the American Embassy in Warsaw – the Rebbe managed to supervise the printing of many volumes of Chabad teachings only through copies that he made when living in Berlin and Paris in the late 1920s and 1930s, and carried with him while travelling across the Atlantic Ocean.

“Things were very different once the Rebbe came,” said Gordon, referring to the Ramash. “They published books of Chabad teachings, books for children, and everything in between. At that time, there was nothing for children or even for adults.

“There were no printed books on Chabad philosophy for us to learn from,” continued Gordon. Once the Ramash sent me to bring edits on galleys on a discourse that he never learned, that today is a staple in Chabad schools, “On the way to the printer by train, I learned an entire discourse. The Ramash’s work filled a great need.”

The Ramash took on many new endeavors, leading the Sixth Rebbe to once tell Rabbi Shlomo Aharon Kazarnovsky that his son-in-law is “never sleeping at 4:00 in the morning. Either he didn’t go to sleep, or he already woke up.”

After the Sixth Rebbe’s passing in 1950, his son-in-law became the leader of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement.

20th Century Communication

“I am scared that Judaism in America will soon be only ceremonial without any Judaism,” a reporter from the Jewish American told the Rebbe during a January 1958 interview.

“I do not see any such danger,” the Rebbe responded. “On the contrary, I see Judaism becoming an organic part of the Jewish community in America. I see in America [that] there will be a great return of the youth to Judaism.

“Today more than ever,” the Rebbe added, “we could do more for Jews and Judaism. Today when we have the means of communication, there is no ‘far away.’ The [opportunity] to do for our fellow Jews is great. In the past, one Jew was cut off from another Jew in another city because the transportation and communication was difficult. However, today when a letter arrives in airmail within a few days, and our communication and transportation is much easier, there is a much greater opportunity to bring Jews closer to Judaism.

“These advances are very important for the perpetuity of Judaism.”

Reflecting on the exchange, the reporter, Pinchus Steinwacks, wrote that “the Rebbe does not give off the aura of a miracle worker. His mission is to keep the flames of Torah alive and if there is a place where it did extinguish, to rekindle it.”

“American Jewry must recognize this sacred, historical mission which Divine Providence has entrusted to it at this critical moment of our struggle for survival,” the Rebbe told Gershon Kranzler, as told in an article published in Orthodox Jewish Life in 1951. “The largest concentration of our best elements are in America. The very shape which Jewry and Judaism of tomorrow will present, depends on the active leadership of each and every Jew in this country.

“America’s great genius has been in the development of the individual, of the pioneering and self-made man type. Although this helped in developing our potentialities by demanding every last ounce of ingenuity and perseverance, it has on the other hand focused too much attention on egoistic aims and interests.”

The Rebbe told him that “we must live the life of social beings, with the responsibility and dedication of our best efforts for the community. Only then can we afford to invest in our own individual aims and goals.”