|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The Jerusalem-based, Australian-born writer tells JNS that Oct. 7 reinforced the urgency of reclaiming Mizrahi memory, resilience and hope.

By: Steve Linde

Sarah Sassoon grew up surrounded by the food, music and warmth of an Iraqi Jewish home in Australia—but without the stories that explained where her family came from or why they had left.

That silence, she says, is what ultimately drove her to become a writer.

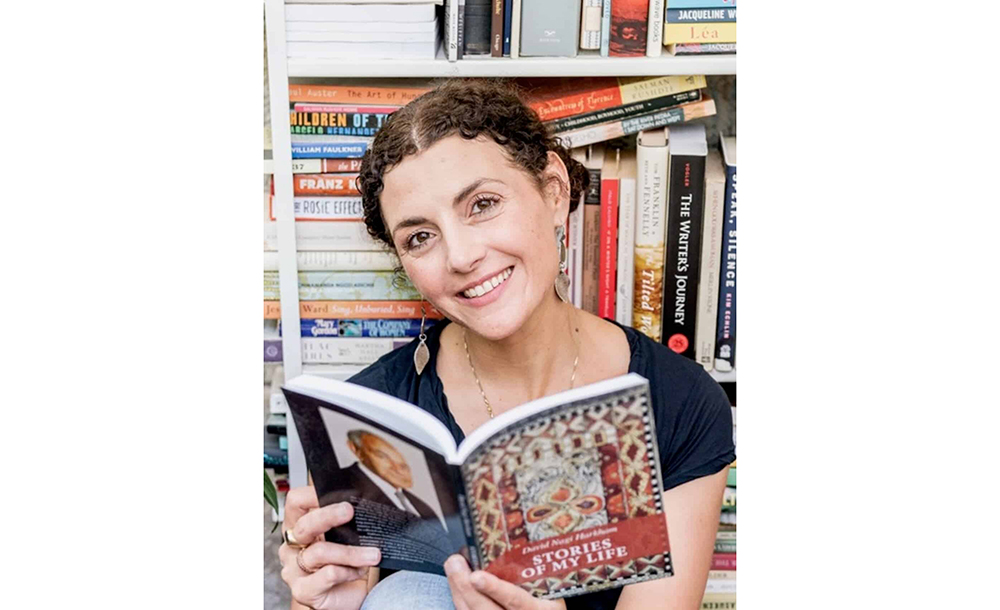

Sassoon, an author, poet and educator who now lives in Jerusalem with her family, has emerged as a leading voice exploring the 2,600-year history of Babylonian Jewry, the experience of refugees and resilience, and the largely untold stories of Middle Eastern Jewish women.

“I grew up with immigrant parents who didn’t speak about their lives in Iraq, or why they had to leave,” Sassoon said in an interview at the JNS Jerusalem studio at the end of January. “There was a silence—and writing became a way of traveling where my family didn’t speak.”

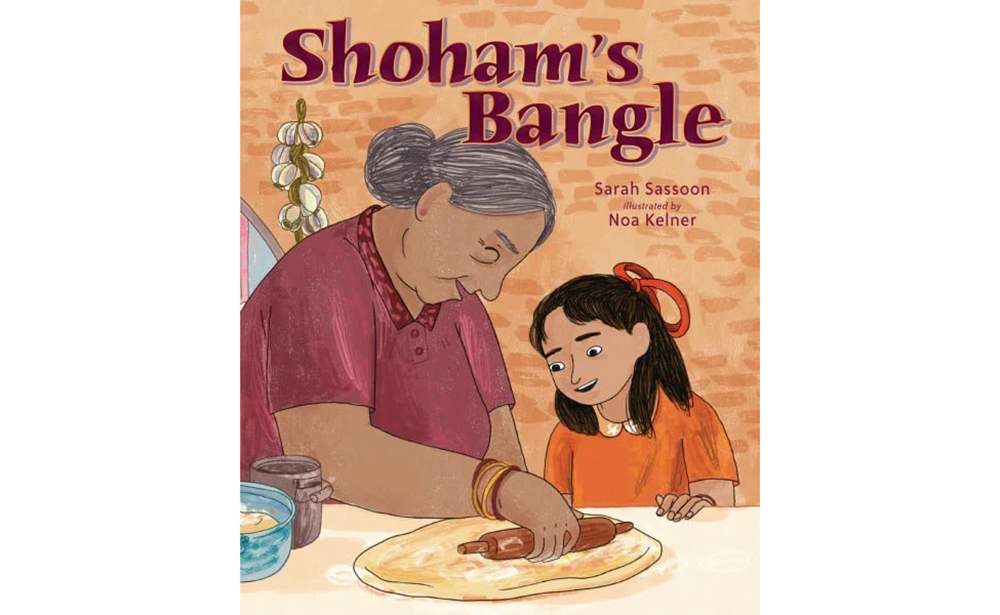

That journey has produced a growing body of work, including two award-winning children’s books, Shoham’s Bangle and This Is Not a Cholent, as well as the poetry micro-chapbook, This Is Why We Don’t Look Back, which won the Harbor Review Jewish Women’s Poetry Prize.

The horrific events of Oct. 7, 2023, she said, gave new urgency to her research into Iraqi Jewish history, particularly the 1941 Farhud pogrom in Baghdad.

“All the red flags I saw in my research suddenly became very present,” she said, drawing parallels between the incitement that led to the Farhud and contemporary antisemitism. “The red hands marking Jewish homes in Baghdad—suddenly I’m seeing red hands again,” she said.

From Sydney to Jerusalem

Born in Sydney to Iraqi Jewish parents whose family fled Baghdad in 1951, Sassoon said she was raised in a Middle Eastern cultural world without being given its historical context.

She learned to cook with her maternal grandmother, Nana Aziza. “I wasn’t told about life in Iraq, or why they had to leave, or even about their early years in Israel,” she said. “I grew up with the food and music, but not the language or the stories.”

That changed when she made aliyah after spending several years with her South African-born husband in Johannesburg, where she taught at the Ezra Nehemia Academy. They moved to Jerusalem and she began writing seriously in community workshops.

“For years, I wrote Ashkenazi stories because those were familiar,” she said. “Then one day I wrote a poem about my Iraqi grandparents, and my writing group told me, ‘That’s what you need to write.’ They were right.”

Sassoon said her love of storytelling is rooted in her family, particularly her grandfather, who was known in the family as a gifted raconteur. Though much of his life story was left unspoken while she was growing up, he later committed his memories to writing, producing a memoir late in life that documented the world of Baghdad Jewry he had lost.

Sassoon sees a direct line between his storytelling and her own work today. “My grandfather was a storyteller,” she said. “Stories were how our family made sense of the world. I’m only now learning how much he carried, and how much he passed on without words.”

Recovering what was lost

Sassoon said her work is driven by a desire to recover what was lost—not only property or status, but memory.

“How do you put 2,600 years of Babylonian Jewish history into a tent camp?” she asked, referring to the harsh conditions faced by Iraqi Jews after arriving in Israel. “So much was erased. My generation is finally able to say: there is so much to be proud of.”

Yet Sassoon strives to convey complexity.

“For every Jew killed in the Farhud, there were Muslims and Christians who saved Jews,” she said. “That’s the difficult truth—to hold both the violence and the humanity.”

That perspective informs her belief that Jews from Arab lands can help bridge cultural divides in the Middle East.

“We need to stop looking at the region with Western eyes,” she said. “The Middle East speaks the language of family. Protection of the family. Dignity. That’s where real connection happens.”

Sassoon co-hosts a new podcast, Ayuni: Voices of Our Jewish Grandmothers, with Dr. Drora Arussy and Dalya Arussy, focused on uncovering the stories of Middle Eastern and North African Jewish women long left out of mainstream narratives.

‘Almond blossoms on the trees’

As a mother of four sons—two of whom have served in the Israel Defense Forces—Sassoon said the past two years have been deeply personal.

“My sons are there to defend everyone here—Jews, Muslims, Druze, Christians,” she said. “It’s not about religion. It’s about basic humanity.”

That ethos also shapes her children’s books. Shoham’s Bangle draws on her own family history, telling the tale of a young Iraqi Jewish girl forced to leave Baghdad for Israel and introducing a new generation of readers to the stories of Middle Eastern Jewish refugees.

This Is Not a Cholent is the story of a girl who enters a cholent competition using her Iraqi grandmother’s Shabbat dish, challenging narrow definitions of Jewish tradition.

“It’s about being proud of where we come from,” she said. “Tradition gives us roots, but it also lets us build new communities.”

Her next picture book, The Oud in the Orchestra, soon to be published in Hebrew by Keter, draws on the story of the Al-Kuwaiti brothers—Jewish musicians whose names were erased from Iraqi culture even as their music endured.

“For years, Middle Eastern Jewish culture was treated as something to be hidden,” Sassoon said. “Now we’re saying: this belongs. Our stories belong.”

Despite the pain of recent years, Sassoon remains hopeful.

“The reality is grim,” she said. “But there are almond blossoms on the trees. There are people across the Middle East who look to Israel as a model of freedom and dignity. That is exactly why our enemies hate us—and exactly why we should be proud.”

(JNS.org)