|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Yehudis Litvak

When the Babylonian army destroyed the First Temple, they also burned down the surrounding area, demolished Jerusalem’s walls, and exiled most of its population.1

Thousands of years later, archeologists excavating in Jerusalem uncovered the destruction layer from the Babylonian conquest, as well as numerous relics from the First Temple era. These findings complement the biblical narratives, allowing us to form a fuller picture of those long-ago events. Below, we share just a small sampling of these findings.

The People

Among the most exciting archeological discoveries are bullae – clay stamp impressions bearing names of important officials, used in official correspondence.

Baruch ben Neriah

A scribe and a close disciple of the Prophet Jeremiah, Baruch ben Neria is mentioned numerous times in the Book of Jeremiah, including a prophecy specifically addressed to him.2

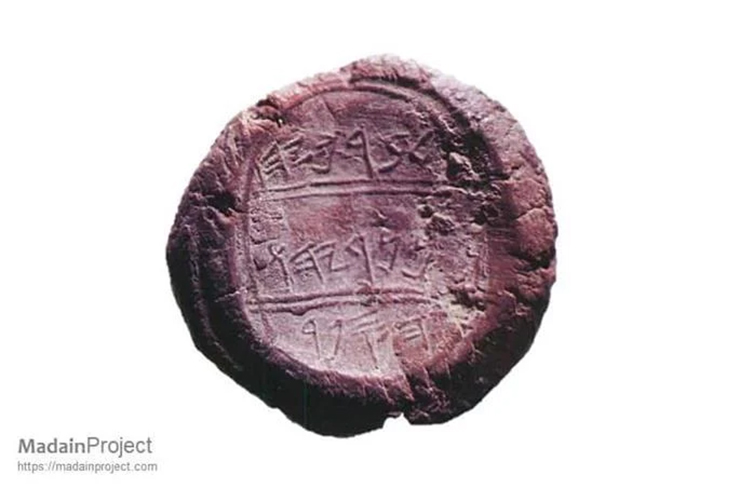

Gemariah ben Shaphan

In the Book of Jeremiah, the prophet instructs Baruch ben Neriah to write down his prophecy in a scroll and to read this scroll in public.4 Baruch ben Neriah read the scroll to the Jews assembled “in the chamber of Gemariah the son of Shaphan the scribe, in the upper court” of the Temple. 5

In 1982, during archeological excavations in the City of David in Jerusalem, Professor Yigal Shiloh discovered an ancient room containing 51 bullae. Among them was the bulla of Gemariah ben Shaphan.6 Unlike the bullae of Baruch ben Neriah, these bullae, discovered by professional archeologists, are unquestionably authentic.

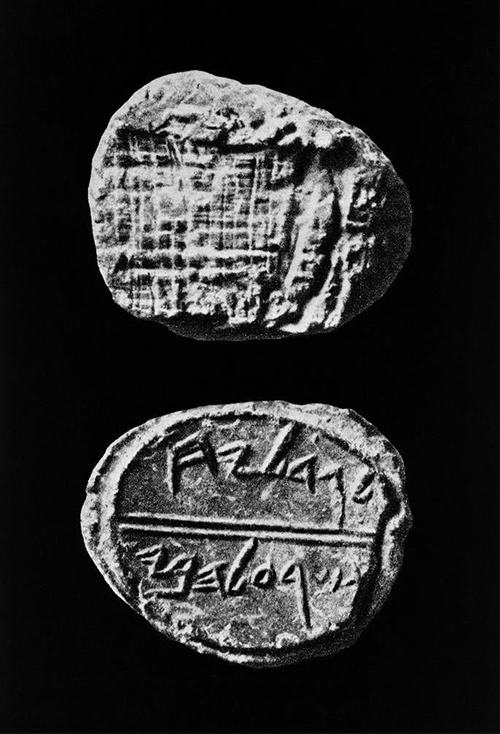

When a bulla with the name “Berachyahu ben Neria” appeared on the antiquities market in 1975, it caused quite a stir. “Berachyahu” is the longer form of “Baruch.” Some immediately proclaimed that the bulla unquestionably belonged to Jeremiah’s scribe, while others insisted that the find was a forgery.

Jehuchal ben Shelemiah

In 2005, while excavating in the City of David, in the area believed to be the ruins of King David’s palace, Israeli archeologist Eilat Mazar discovered a bulla with the name Jehuchal ben Shelemiah ben Shovi. The bulla is unusual in that it mentions both the father’s and the grandfather’s names.

Though the name Shovi is not mentioned in biblical sources, Jehuchal ben Shelemiah is mentioned twice in the Book of Jeremiah. During a lull in the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem, Zedekiah, the last king of Judah, sent two officials to Jeremiah, asking him to pray for the Kingdom of Judah. One of those officials was Jehuchal ben Shelemiah.7

Later, Jeremiah was imprisoned for advocating surrender to the Babylonians, but from within the prison he continued his attempts to convince the people to surrender and save their lives. Several high-ranking officials heard his words, approached King Zedekiah, and demanded that Jeremiah be put to death for weakening the defenders’ morale. One of those officials is named as Jechal ben Shelemiah, a shorter version of Jehuchal.8

Later, an identical bulla was also purchased on the antiquities market, but this one contained a fingerprint. Many wondered if it could be the fingerprint of Baruch ben Neriah himself.

Archeologists still continue to debate the matter. It is impossible to decisively determine the bullae’s authenticity because they were not discovered in archeological excavations. However, in 2016, archeologists Pieter Gert van der Veen and Robert Deutsch published a thorough rebuttal to the arguments and evidence used to claim that the bullae are forgeries.3

Gedaliah ben Pashchur

In 2007, while continuing the excavation in the City of David, Professor Mazar found the bulla of Gedaliah ben Pashchur, another official who demanded the death penalty for Jeremiah, along with Jehuchal ben Shelemiah.9

Though discovered two years apart, the two bullae were located only a few feet away from each other, in the vicinity of the royal palace. There is no question as to their authenticity.

Gedaliah ben Achikam

After destroying the Temple and exiling most of Judah’s residents to Babylonia, King Nebuchadnezzar’s chief executioner, Nebuzaradan, left “some of the poorest of the land as vine-dressers and farmers.”10 Nebuchadnezzar appointed Gedaliah ben Achikam to govern those remaining.

A bulla dating from the time of the destruction was discovered at Lachish, a fortified city back in the days of the Kingdom of Judah. The inscription on the bulla reads, “Gedaliahu [appointed] over the house.” “Gedaliahu” is the longer form of “Gedaliah.”

Scholar and author Rabbi Yehuda Landy explains that “appointed over the house” means “responsible for the royal court.”11 The word “house” is also used by Jeremiah in connection with Gedaliah ben Achikam, so it is very possible that the bulla belonged to him.

Rabbi Landy says that Gedaliah ben Achikam likely served in a senior position at the royal court before the Babylonian conquest, and the Babylonians trusted him because he had surrendered to them during the siege of Jerusalem.12

Jaazaniah, Servant of the King

Another bulla from the same time period has two lines of text and a picture of a rooster at the bottom. The text reads “Jaazaniah, Servant of the King.”

Perhaps the bulla belonged to Jaazaniah, the son of the Maachathite, who joined Gedaliah ben Achikam after the destruction of Jerusalem.13 Interestingly, the bulla was found in Mitzpeh, precisely where, according to II Kings, Jaazaniah and several other high-ranking army officers from Judah approached Gedaliah.14

The Battle for Jerusalem

During the First Temple era, Jerusalem–surrounded by a thick wall–primarily comprised the Temple Mount, the City of David, and the Ophel area that connected the two. Though most of the surrounding wall was destroyed by the Babylonians, archeologists discovered small segments that survived and were later incorporated into the rebuilt wall when the Jews returned from exile.15

Slingstones and arrowheads, both Babylonian and Judean, were discovered in several locations along the ancient city wall, attesting to the battles that took place between the Babylonians and Jerusalem’s defenders.

Archeologists found a defensive tower (in today’s Jewish Quarter) dating back to the late First Temple era. At the time, it would have been located next to the northern wall of Jerusalem. Arrowheads and ash were found at the foot of the tower.

Rabbi Landy explains:

Apparently, a fierce battle between the Babylonian soldiers attacking the city and the Jewish defenders occurred here. The tower was probably part of the array of fortifications of the northern wall of the city. From a topographic perspective, this is the most logical point from which to launch an assault against the city, since the area beyond it to the north is higher than the level of the city. In other directions, the city is surrounded by valleys, and there would be no sense in attempting to break into the city from there.16

The northern wall was likely the one that was breached when the Babylonians conquered Jerusalem.17

The Fire

After conquering Jerusalem, Nebuzaradan, King Nebuchadnezzar’s chief executioner, “burnt the house of the L-rd and the king’s palace, and all the houses of Jerusalem and all the houses of the dignitaries … 18”

Signs of destruction by fire, such as ashes, charred wood, and blackened stone, were found throughout the area of First-Temple-era Jerusalem.

In recent years, archeologists excavating in the City of David have analyzed the microscopic remains of fire using the latest technological advances, such as measuring infrared light absorption and the Earth’s magnetic field. These techniques enable archeologists to form a fuller picture of what occurred at those locations during the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem.

One of the sites studied is what the archeologists call Building 100, located at the Givati Parking Lot archeological site in the City of David. The two-story building, dating to the First Temple era, is one of the largest known from that time period, measuring 10 x 17 meters. Based on its architectural style and unique finds, archeologists hypothesize that it was used by Jerusalem’s elite.19 Perhaps it was one of the houses of dignitaries burned down by Nebuzaradan.

In 2023, a team of Israeli archeologists applied the modern techniques to the charred remains found throughout the excavated part of Building 100. They were able to trace the origins and the path of the fire, concluding:20

The widespread presence of charred remains suggests a deliberate destruction by fire, which was ignited at several locations in the top and bottom floors, with heat rising to burn the ceiling of the bottom floor. The rapid collapse of the structure probably hastened the suffocation of the fire … [T]he spread of the fire and the rapid collapse of the building indicate that the destroyers invested great efforts to completely demolish the building and take it out of use.

This research shows that the Babylonian efforts to destroy Jerusalem were far from haphazard. They made sure to devastate the city, leaving it desolate until Jews were able to return from Babylonia and rebuild it.

Footnotes

- II Kings 25.

- Jeremiah 45.

- Van der Veen, P. G., & Deutsch, R. Reconsidering the Authenticity of the Berekhyahu Bullae: A Rejoinder.

- Jeremiah 36.

- Jeremiah 36:10.

- The Seal Impression of Gemaryahu Son of Shaphan. Cityof David.org.il.

- Jeremiah 37:3.

- Jeremiah 38:1.

- Jeremiah 38:1.

- II Kings 25:12.

- Rabbi Yehuda Landy. Uncovering Sefer Yirmiyahu: An Archeological, Geographical, Historical Perspective.

- Rabbi Yehuda Landy. Uncovering Sefer Yirmiyahu: An Archeological, Geographical, Historical Perspective.

- II Kings 25:23.

- Seal of Yaazanyahu (Jaazaniah), Servant of the King, with Rooster. Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization.

- Rabbi Yehuda Landy. Uncovering Sefer Yirmiyahu: An Archeological, Geographical, Historical Perspective, pp. 11-13.

- Rabbi Yehuda Landy. Uncovering Sefer Yirmiyahu: An Archeological, Geographical, Historical Perspective, p. 147.

- IRabbi Yehuda Landy. Uncovering Sefer Yirmiyahu: An Archeological, Geographical, Historical Perspective, p. 278.

- II Kings 25:9.

- N. Shalom, et al. Destruction by fire: Reconstructing the evidence of the 586 BCE Babylonian destruction in a monumental building in Jerusalem, Journal of Archaeological Science, Vol. 157.

- N. Shalom, et al. Destruction by fire: Reconstructing the evidence of the 586 BCE Babylonian destruction in a monumental building in Jerusalem, Journal of Archaeological Science, Vol. 157.