Rabbi Mendel Kalmenson and Rabbi Zalman Abraham discuss their new book

By: Bruria Efune

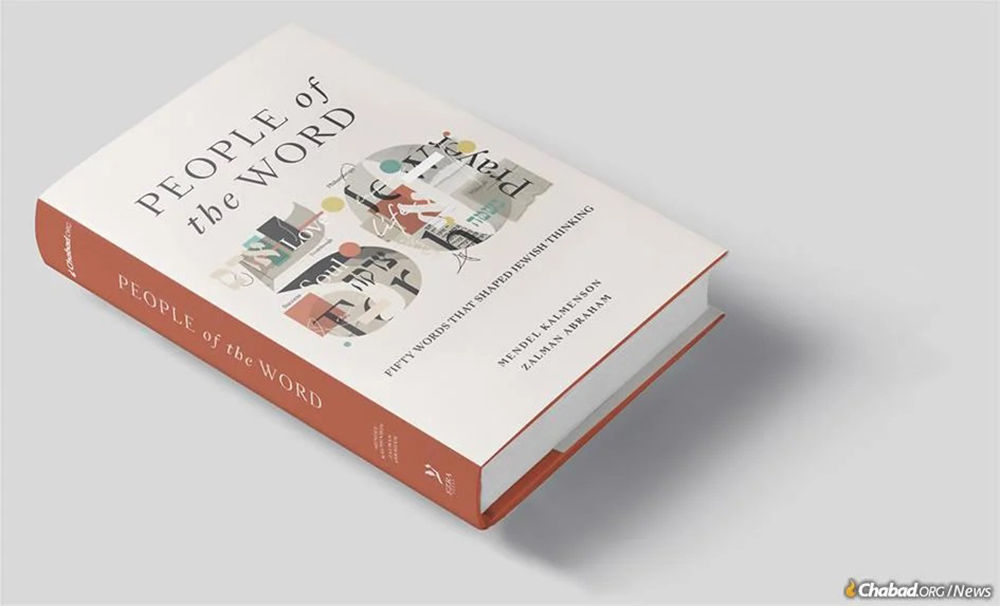

Love, suffering, success, intelligence . . . What do these words tell you about the Jewish people? These words may mean something entirely different in Biblical Hebrew—in a way that has shaped a nation for millennia. In People of the Word: Fifty Words that Shaped Jewish Thinking (Ezra Press and Chabad.org), Rabbis Zalman Abraham and Mendel Kalmenson dissect 50 Hebrew words, and dive into their definitions and the hidden messages found inside each of them.

It’s a rare journey through the history, culture and dreams of a nation—much of which may have been lost in the languages of host countries through which the Jewish people wandered for the past 2,000 years. As the authors explore each word, they also uncover gems that put each idea into a uniquely Jewish perspective, often challenging the reader’s prior understanding.

In a conversation with Chabad.org, the co-authors shared their passions behind the book, each displaying their individual—and often very different—outlook and style. Rabbi Zalman Abraham brings his 13 years of experience planning and writing popular courses for the Jewish Learning Institute (JLI). Rabbi Mendel Kalmenson’s resume includes serving as rabbi and executive director of Chabad of Belgravia in London, and author of several widely successful books, including the highly acclaimed Positivity Bias and Seeds of Wisdom.

Their synergy leads to a book that is surprisingly difficult to put down and meets every type of reader from the academic to the casual, and from the advanced Judaic learner to the beginner.

Here the authors answer several questions, revealing their fascinating intentions behind People of the Word.

Q: In the introduction to People of the Word, you write about how the words a nation uses shape its unique culture and ethos, and you give several fascinating examples. How did each of you become interested in this phenomenon, and what led you to explore the impact of the Hebrew language on the Jewish people?

Zalman Abraham: For full disclosure, the idea for creating such a book was completely Mendel’s, as was the angle of words shaping culture. What drew me to this genre was more of an interest in capturing the insight that words provide into a nation’s culture and ethos, and not so much how they shape it.

I think most people analyze words as a way to gain a better understanding of things. My maternal grandfather, of blessed memory, trained me to reach for a dictionary at every turn to gain a more precise definition for words that seem somewhat ambiguous. I do this several times a day using Google’s “define:WORD” feature.

Turning to etymology is also a common technique that I’m familiar with from my yeshivah education. Particularly from Rashi, the classical biblical commentator, who places a tremendous emphasis on etymology, building on the work of his predecessors in comparing different usages of a word to decipher cryptic biblical terms. Chassidic texts often use etymology to drive home a more accurate and nuanced meaning of a term and to point out the foundational basis for a particular insight.

Additionally, as a visual learner, I find that concepts are depicted in pictorial form differently in different cultures because of the attributes referenced in words used to describe them. For example, the English word “sifting” depicts the use of a sieve for sorting larger granules from smaller granules. It’s just a technical act of sorting, no different from sorting cards. In Talmudic texts, the word for sifting is meraked, which means to dance, depicting the granules jumping up and down in the sieve. Another (more modern) Hebrew term for this is lenapot, which describes the act of waving (hanafa) and shaking the sieve to and fro. Depending on which word you use, the visual mind can depict sorting flour as sorting cards, as granules dancing on a trampoline, or as shaking an instrument (think tambourine). The activity might be the same, but it paints a different picture in your mind.

I must admit, I didn’t fully appreciate the practical, spiritual and religious significance of etymology (I viewed it as more of a trivial novelty, kind of like Bible codes) until I chanced upon a talk by the Rebbe [Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory] that explains that the purpose for which everything was created—the way that thing exists in its most perfect and complete state—is coded into the etymology of its Hebrew name. And that, before the Torah was given, the primary purpose of humans on earth was to assist in bringing everything to that perfect state as described in its name. After seeing this, I knew there was something fundamental in Hebrew etymology, something that was beckoning to be explored further, a new genre that existing Jewish literature has barely tapped into.

Mendel Kalmenson: A number of years ago, I was one of many guests at the Sukkot table of a member of the Chabad community of Atlanta, Ga. During the meal, he invited everyone present to ask any questions on their mind. One woman stood up and said, “I’m actually deeply offended by something in your sukkah.”

She pointed to an electronic board that had messages floating across the display. It read: “Do Not Pray, Do Not Repent, and Do Not Give Charity.” She explained that she found it jarring, coming right after the High Holiday season, when one of the essential prayers is that teshuvah tefillah utzedaka maavirim roeh hagezerah—repentance, prayer and acts of charity can avoid or revert a negative decree—highlighting that these three spiritual practices are fundamental pillars in Jewish tradition.

The host was smiling, as clearly he had planted the gimmick for just this moment. He then launched into a well-known teaching of the Rebbe that these three words have been mistranslated and misunderstood for millennia.

Jewish people, especially those who lived in Christian host countries, have been influenced to see the world through a Christian lens, so these three ideas in Judaism have unfortunately become tainted by a different way of thinking, other than the original Jewish worldview.

If you open a Webster’s Dictionary, “prayer” is synonymous with “petition,” or “lobby.” These suggest that prayer is done when one has a lack or need to be fulfilled and petitions a higher deity.

Whereas in the Jewish tradition, the word tefillah appears early in the Torah in the context of Leah naming her son Naftali, which means to “bond.” She’s thanking and asking G‑d that through this child she will grow closer to her husband, Jacob.

So prayer is not merely transactional, there to facilitate a need; it’s a spiritual exercise aimed at fostering intimacy with the divine. It’s a conversation, a bid for connection, a touchpoint to express and deepen the closeness between ourselves and our creator.

The idea of repentance in many traditions in the wider sense, is to become someone/something new. There’s a notion in Christianity about being “born again.” In the Jewish tradition, the literal meaning and essential theme of the word teshuvah is tashuv, “to return” to who you really are. In other words, we each have a point of goodness and G‑dliness that cannot be corrupted and always maintains its spiritual innocence and integrity. It’s irrevocably and unconditionally connected to the Almighty. The process of teshuvah, then, is simply shedding the distortions and distractions that come with the wear and tear of physical existence, and realigning with our truest core and essence. Hence, teshuvah is not about becoming the new you but becoming the real you.

The Hebrew word tzedakah doesn’t translate to English, because it means both “charity” and “justice.” In English, that simply doesn’t work because paying a debt is justice, whereas gifting money is charity—the two don’t mix. But in Hebrew there’s no word for charity without justice, because giving is something that we have to do.

After this fateful exchange in the Sukkah, I began to notice how so many of the deepest spiritual principles, and fundamentals of Judaic and Chassidic thought, are often embedded in one word. I began to collect these words because they’re truly remarkable. Each one conveys an entire worldview and frame of reference, and helps provide a paradigm shift into the teachings of Judaism and the unique worldview of Chassidus.

This idea inspired me to delve deeper, and that’s how the book came about.