|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Yehudis Litvak

The Old City of Jerusalem is home to several historic synagogues where prayer services are still conducted today. The oldest and most famous is, of course, the Western Wall, a remnant of the retaining wall of the Temple Mount from the Second Temple era. In this article, we will focus on the other historic synagogues within a few minutes’ walk from the Western Wall.

- The Ramban Synagogue

Said to have been founded by the Ramban, 13th-century Torah scholar Rabbi Moses ben Nachman (Nachmanides), the Ramban Synagogue is among the oldest active synagogues in Jerusalem.

Nachmanides was born in Spain in 1195, where he lived for the majority of his life. For many years, he taught Torah, wrote books, and practiced medicine in his native city of Gerona. At age 70, he was summoned to Barcelona to participate in a disputation with Christian scholars.

Although Nachmanides’ brilliant defense of Judaism impressed the king, it angered his enemies. Realizing that his life was in danger, he left his native Spain and set out for the Land of Israel at age 72.

Arriving in Jerusalem in 1267, three weeks before Rosh Hashanah, Nachmanides found only two Jews living there, brothers who worked as textile dyers. Most of Jerusalem’s Jewish community had been wiped out two years earlier by the Tatar invaders, and the other survivors had fled to Shechem.1

Nachmanides set out to revive the Jewish community. In the aftermath of the invasions and battles, Jerusalem was left with many ownerless ruins, and he and the two dyers looked for a suitable place for a synagogue.

In a letter to his son, he wrote:

We afterwards found a very handsome ruinous building, with marble columns and an elegant cupola; we instituted a collection to restore it to answer as a Synagogue; we then commenced the rebuilding, and sent for the Torah scrolls to Shechem, whither they had been conveyed for safety; and now we have a handsome regular Synagogue, where public divine service is held; for there are constantly arriving here brothers and sisters in the faith from Damascus, Aleppo, and the whole surrounding country, in order to see the ruined temple, and to weep and mourn over it.2

Within a couple of weeks, the new synagogue was cleaned up and ready for use. On Rosh Hashanah, Nachmanides gave a sermon encouraging the new arrivals to stay in Jerusalem.3

Although he himself eventually left and settled in Acre (where he died in 1270), Jerusalem’s Jewish community and the synagogue that he began continued to grow.

The exact location of the synagogue’s original building is unknown, but it is presumed to have been on Mount Zion.4 In the 15th century, the synagogue moved to its current location on Hayehudim Street in the Jewish Quarter.5

The current building was constructed a few meters below street level, likely to comply with the Islamic law requiring non-Muslim houses of worship to be lower than mosques.

For centuries, the Ramban Synagogue remained the only synagogue in Jerusalem, and both Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews gathered there to pray.

Ottoman authorities ordered the synagogue’s closure in 1586, following complaints from the local Muslims that “the noisy ceremonies of the Jews in accordance with their false rites hinder our pious devotion and divine worship.”6

The synagogue building was confiscated and subsequently used as a raisin mill and cheese factory.

During Israel’s 1948 War of Independence, Jordanian troops conquered the Old City of Jerusalem, captured or exiled its Jewish residents, and destroyed its synagogues.

Two decades later, during the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel liberated the Old City and began the process of restoring its synagogues and Jewish institutions. The Ramban Synagogue was located, restored, and returned to daily use.

- The Churvah Synagogue

Called “ruin” (churvah in Hebrew), the Churvah Synagogue lay in ruins for many years until it was rebuilt into a magnificent domed structure in 2010, housing one of the tallest Torah arks in the world.

The synagogue was founded in 1700 by Ashkenazi Jews newly arrived from Europe, led by Rabbi Yehudah Hachassid, a Torah scholar and charismatic speaker from Poland, whose sincere and heartfelt yearning for the Land of Israel inspired 1,500 people to join him in settling in Jerusalem.

One of the travelers, Rabbi Nasan Nata, described the group:

A huge [congregation] of uplifted Jews. Each G‑d-fearing individual (including elders and scholars of esteem) stood with a luster shining about him. At their head was one full of wisdom, an angel of G‑d, Rabbi Yehudah … (they all were) with one intention: to go and ascend to Jerusalem, the place of our inheritance.7

The journey was arduous and fraught with dangers, and about a third of the group perished on the way. Despite the heavy losses, their arrival was a cause for celebration for the whole Jewish community of Jerusalem.

Within a couple of days, Rabbi Yehudah signed a contract with the local Arabs to purchase property for a synagogue and courtyard surrounded by a 42-room structure.

That Shabbat, Rabbi Yehudah, who was in his sixties, suddenly fell ill. He passed away on Monday, leaving his community leaderless and in a state of shock.

Meanwhile, the Arabs who had sold Rabbi Yehudah the property demanded more and more money. In addition to immediate costs, they charged extra taxes and expected bribes.

Rabbi Gedaliah, a member of the group, wrote:

These taxes were unforeseen and caused us to go into debt. Moreover, as we had to pay bribery money for every little thing the Arabs did for us, our debts mounted further … Within no time, the debts zoomed over our heads. As soon as we got out of the clutches of one Arab lender, we fell into the hands of another.

Before long, we were afraid to walk in the streets during the day, for fear that one of them would apprehend us. At home, the situation was also appalling, as we lacked the most basic necessities.8

As the Arabs grew increasingly frustrated with the unpaid debts, the new arrivals, unfamiliar with the local language and customs, struggled to make a living.

In 1720, the Arab lenders’ patience ran out. On Shabbat, they stormed the synagogue and set it on fire. They burned Torah scrolls and prayer books. Only the stone walls remained. The congregants were banished from Jerusalem and their property confiscated. It was then that the synagogue was named the Churvah.

For the next hundred years, no Ashkenazi Jew was permitted to live in Jerusalem. The few who managed to sneak into the city dressed like Sephardim and joined the Sephardic community.

After much negotiation and some intervention by Sir Moses Montefiore, the Ottoman authorities finally permitted Ashkenazi Jews to return to Jerusalem and rebuild their synagogue, which was completed in 1864. With its dome towering above the surrounding buildings, the synagogue immediately became a Jerusalem landmark.

In 1948, the Churvah Synagogue was destroyed by the Jordanian troops, just like the rest of the Old City’s synagogues. Again, it lay in ruins for decades, with a lone arch a sole reminder of its former glory.

Even after the liberation of the Old City in 1967, the Israeli authorities took time deciding how to restore the synagogue. Finally, after much deliberation and planning, it was rebuilt in 2010.

Today, prayer services are conducted regularly, and in between services, the building is open to tourists, who can view its magnificent interior, learn about Jerusalem’s history, and see the Old City from its rooftop.

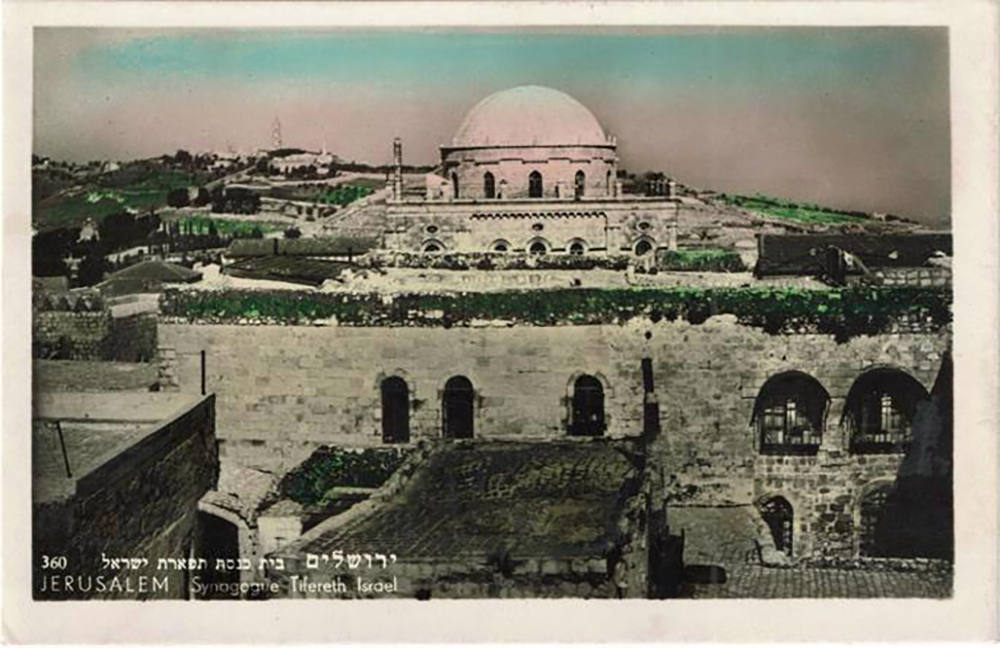

- The Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue

Before 1948, the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue was another Jerusalem landmark, similar in appearance to the Churvah Synagogue, its domed roof towering above the Jewish Quarter.

The Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue was built by the Chassidic community in the mid-19th century. Inspired by the revival and growth of Jewish life in Jerusalem, and with the encouragement of their Rebbes, many Chassidic Jews were immigrating from Europe and settling in Jerusalem. At first, they joined the existing synagogues or held services in private homes, but as their population grew, they wanted to establish their own.

One of the leaders of the Chassidic community in Jerusalem was Rabbi Yisrael Beck, who owned a printing press. His son, Rabbi Nissan Beck, traveled to Europe in 1843 and met with Rabbi Yisrael Friedman, the Ruzhiner Rebbe.

At the meeting, they discussed Tsar Nicholas I’s plan to purchase a plot of land in the center of Jerusalem’s Old City to build a church and a monastery. The Jewish community was very concerned that the Russian construction would divide the Jewish Quarter and block access to the Western Wall.

The Ruzhiner Rebbe urged Rabbi Nissan Beck to offer the Arab landowner a larger amount and purchase the land for the Jewish community. The Ruzhiner Rebbe himself contributed a large sum towards this purpose.

Upon his return to Jerusalem, Rabbi Beck successfully negotiated with the landowner and signed a purchase contract. The disappointed tsar had to settle for a different plot of land, outside the Old City, which is still referred to as the Russian Compound.

The Chassidic community began building a synagogue on the newly acquired land, but it took many years to complete, due to opposition from the Ottoman authorities as well as a lack of funds.

By 1866, all the necessary permits had been obtained and the construction finally began. In 1869, the building stood, but the community lacked funds to complete the domed roof.

That year, Emperor Franz-Joseph of Austria-Hungary visited Jerusalem on the occasion of the completion of the Suez Canal and received an appropriately royal reception. On his itinerary was a tour of the Old City, where Rabbi Nissan Beck served as his translator.

When the emperor saw the unfinished building of the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue, he asked what had happened to its roof.

“The synagogue took off its hat in your honor,” replied Rabbi Beck.

The emperor laughed, but he understood that the Jewish community did not have the funds to complete the roof. Shortly after his visit, he sent a large donation to cover the expenses.

In 1872, the building was finally completed and inaugurated. It continued to serve as the spiritual home of the Chassidic community until it was destroyed by the Jordanian troops in 1948.

Today, the restoration of the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue is still ongoing. It is scheduled to be completed in 2026.

- The Beit El Synagogue

Right across the plaza from the Churvah Synagogue is a two-story building with a decorative metal door. It is the home of the Beit El Synagogue and Kabbalist yeshivah, founded in 1737 by Rabbi Gedaliah Chayun, who came to Jerusalem from Constantinople.

Rabbi Chayun was a scholar of Kabbalah, which he taught to a small circle of disciples. In Jerusalem, he became known as “leader of the pious.” He led prayer services in Beit El, meditating on each word in a mystical manner.9

After Rabbi Chayun’s death in 1751, Rabbi Shalom Sharabi from Yemen took over the synagogue and yeshivah and moved into the apartment above the synagogue with his family. Under Rabbi Sharabi’s leadership, the yeshivah attracted many students of Kabbalah, who later became known as scholars in their own right.

Study of Kabbalah continued in Beit El throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1927, an earthquake cracked the building’s roof. Afraid that the roof might collapse, the British Mandate authorities ordered the building’s demolition.

Pained by the loss of their synagogue, the community immediately began planning to rebuild. The new building was completed in eight months.

In 1948, when the soldiers of the Arab Legion entered the synagogue building, its ceiling caved in, killing them on the spot.10

In 1974, Tunisian-born Rabbi Meir Yehuda Getz, who served as the rabbi of the Western Wall, reestablished the Beit El yeshivah in its original location, where it remains active today.

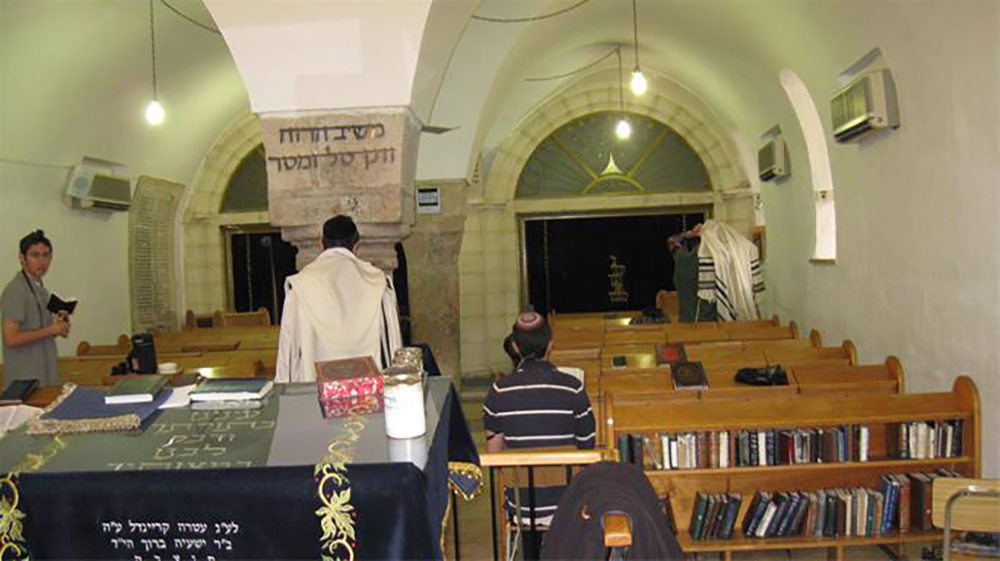

- The Tzemach Tzedek Synagogue

Founded in 1845 by a group of Chabad chassidim, the Tzemach Tzedek Synagogue is located across the street from the Churvah plaza, above the ruins of an ancient Roman street known as the Cardo.

The synagogue’s founders turned to known Jewish philanthropists for help with the building. Sir Moses Montefiore of Britain and Elias David Sassoon of India contributed funds towards the land purchase and construction.11

The synagogue was in continuous use until 1948, when it was captured by the Jordanian legion and used as an ammunition depot (and later as stables and shops).12

The building survived intact, and as soon as Jerusalem’s Old City was liberated in 1967, Rabbi Moshe Segal, a prominent figure in Chabad who had participated in the War of Independence, headed straight to the Tzemach Tzedek Synagogue and began the process of cleaning and restoration. Rabbi Segal slept in the synagogue building, with a gun under his head, guarding it until the Chabad community returned to the Old City and resumed regular synagogue services.13

Today, the Tzemach Tzedek Synagogue continues to host prayer services, as well as lively Shabbat meals open to Jerusalem’s visitors.

The Four Sephardic Synagogues

A short walk south of the Churvah and Beit El synagogues is a complex of four adjoining Sephardic synagogues.

Built during Ottoman rule, these too are located below ground level, likely in compliance with Muslim regulations requiring non-Muslim houses of worship to be lower than mosques.

Perhaps because of their low construction, these synagogues were spared from destruction when Jordanian troops conquered the Old City in 1948. Instead, the buildings were used as sheep and goat pens.

When Israel liberated the Old City in 1967, the Israelis had to clear mounds of refuse before repairing the synagogue structures.14

- The Eliyahu Hanavi Synagogue

The Eliyahu Nanavi Synagogue, the oldest of the four, was established after the Ottoman authorities closed the Ramban Synagogue at the end of the 16th century. The building also housed the Talmud Torah yeshivah.

A story is told about the early days of the synagogue, when Jerusalem’s Jewish population was still small. One Yom Kippur, only nine men gathered for prayers. They were disappointed that they would not be able to pray with a minyan on the holiest day of the year. Suddenly, an old man, whom no one knew, walked into the synagogue. Overjoyed, the small congregation began to pray. The old man stayed throughout Yom Kippur and disappeared right after the final service, refusing the offers of food to break the fast. The congregants understood that the old man was none other than Eliyahu Hanavi, the prophet Elijah, and named the synagogue in his honor.

- The Yochanan ben Zakkai Synagogue

The Yochanan ben Zakkai Synagogue, the largest of the four, is named after the sage who is said to have taught Torah at this exact location towards the end of the Second Temple era.

In 1893, the inauguration ceremony of the Sephardic Chief Rabbi was held in the Yochanan ben Zakkai Synagogue, with both Ashkenazic and Sephardic communities in attendance. An eyewitness explained that the celebration was held in the largest Sephardic synagogue, “so that all the people of our city, both sages and multitudes, could watch the appointment of the rabbi whose honor would reflect their own.”15

Other Sephardic Chief Rabbis have since been inaugurated at the Yochanan ben Zakkai Synagogue, including the current title-holder, Rabbi David Yosef.

- The Istanbuli Synagogue

The Istanbuli Synagogue was established in the mid-18th century by Jews from Turkey. Later, Sephardic Jews from other locales joined the community, but the name remained. A plaque at the entrance records that the building was renovated in 1836. Today, the building is used by the Spanish-Portuguese community.

- The Emtzai Synagogue

As the Sephardic community grew, the need for another synagogue became apparent. The women’s section of the Yochanan ben Zakkai Synagogue was converted into a separate synagogue, called the Emtzai (Middle) Synagogue. (Chabad.org)

Footnotes

- Nachmanides’ letter to his son, cited in Rabbi Joseph Schwarz’s Descriptive Geography and Brief Historical Sketch of Palestine.

- Nachmanides’ letter to his son, cited in Rabbi Joseph Schwarz’s Descriptive Geography and Brief Historical Sketch of Palestine.

- Larry Domnitch. The Ramban Synagogue: Hope Amidst Despair.

- Larry Domnitch. The Ramban Synagogue: Hope Amidst Despair.

- According to the plaque on the synagogue building.

- Norman Stillman. The Jews of Arab Lands: A History and Source Book, p. 302.

- Quoted in Dovid Rossoff’s Where Heaven Touches Earth: Jewish Life in Jerusalem from Medieval Times to the Present, p. 112.

- Quoted in Dovid Rossoff’s Where Heaven Touches Earth: Jewish Life in Jerusalem from Medieval Times to the Present, p. 115.

- Dovid Rossoff. Where Heaven Touches Earth: Jewish Life in Jerusalem from Medieval Times to the Present, p. 132.

- Dovid Rossoff. Where Heaven Touches Earth: Jewish Life in Jerusalem from Medieval Times to the Present, p. 137.

- Joel Haber. A Jerusalem Landmark: Chabad’s Tzemach Tzedek Shul.

- Tamar Runyan. Lives Intersect at Historic Jerusalem Synagogue.

- Tamar Runyan. Lives Intersect at Historic Jerusalem Synagogue.

- Elchanan Reiner. The Yochanan Ben Zakkai Four Sephardi Synagogues.

- Elchanan Reiner. The Yochanan Ben Zakkai Four Sephardi Synagogues.