|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Russ Spencer

Maurice Tempelsman, the enigmatic diamond magnate whose life intertwined the spheres of politics, wealth, African resource markets, and high society, died on Saturday in Manhattan at the age of 95. His death, at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, followed complications from a fall, according to his son Leon.

To the broader public, Tempelsman is perhaps most widely remembered as the final companion of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, standing steadfast at her side during her final illness and at her funeral in 1994. But his life story stretched far beyond that romantic chapter. As The New York Times has long documented, Tempelsman embodied the contradictions of 20th-century global capitalism: an Orthodox Jewish refugee from Antwerp who became one of the most powerful diamond traders in the world; a figure of discretion who nonetheless cultivated relationships with presidents, African autocrats, liberation leaders, and business titans; and a man whose fortune and influence grew from operating in the murky crossroads of decolonization, Cold War geopolitics, and America’s insatiable appetite for resources.

Maurice Tempelsman was born on August 26, 1929, in Antwerp, Belgium, to Leon and Helen (Ertag) Tempelsman. His father worked in the commodities trade, and the family observed Orthodox Judaism. When Nazi Germany invaded Belgium in 1940, the Tempelsmans fled to New York City, joining a community of fellow refugees on the Upper West Side. Among them was the family of Lilly Burkos, whom Tempelsman would marry in 1949. They had three children—Rena, Leon, and Marcy—and while the couple remained legally married until Lilly’s death in 2022, they were long separated.

As The New York Times noted in a retrospective, Tempelsman’s early life in America bore all the hallmarks of an immigrant family reinventing itself. He studied briefly at New York University before dropping out to join his father in business. In 1950, while barely in his 20s, he struck gold—figuratively speaking—by persuading the U.S. government to purchase African industrial diamonds for its Cold War strategic stockpile. Acting as a middleman, Tempelsman bought diamonds from African suppliers, resold them to Washington, and amassed millions. The Times emphasized that these early deals foreshadowed his lifelong genius for positioning himself at the intersection of natural resource flows, global politics, and American strategic interests.

Tempelsman’s career as a diamond merchant was built not only on shrewd business acumen but on a profound understanding of geopolitical transition. As African nations shook off colonial rule in the 1950s and 1960s, he was among the first Western businessmen to see opportunity in the new order. In 1956, at the age of 27, he traveled with Adlai Stevenson II, the Democratic statesman and his lawyer, to the Gold Coast (soon to be Ghana). There, he secured one of the first diamond-buying licenses from local diggers.

As The New York Times has reported, Tempelsman recognized that decolonization would upend the traditional dominance of European cartels like De Beers. He positioned himself as a nimble outsider capable of navigating relationships with African leaders. His network expanded rapidly: he courted Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire, and later maintained ties across the political spectrum, from Marxist governments to right-wing autocracies.

But these ventures also brought controversy. Insight magazine, citing declassified Kennedy administration documents, later reported that Tempelsman’s associates in Ghana had pushed for Nkrumah’s ouster amid fears that his socialist policies endangered diamond markets. Nkrumah was deposed in a 1966 coup. In Zaire, Tempelsman became one of Mobutu’s key business partners, securing the lucrative Tenke Fungurume mine concession after persuading Washington and Western allies to support the colonel’s rise.

“Somebody had to win, and I guess we won that one,” Tempelsman reflected decades later, acknowledging to Insight the moral ambiguities of aligning with Mobutu, whose rule became synonymous with kleptocracy. “I wish now we hadn’t.”

The New York Times, in its extensive coverage of his career, emphasized that Tempelsman’s dealings in Africa exemplified the way resource extraction, political influence, and Cold War strategy were braided together in ways that blurred the line between commerce and covert intervention.

In the United States, Tempelsman cultivated ties that spanned the Democratic Party establishment. A confidant of Stevenson, he later forged close relationships with John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and particularly Bill Clinton. His fundraising prowess made him a valued Democratic ally, with contributions exceeding half a million dollars in the 1990s alone, according to The Nation and cited in The New York Times report.

The Times reported in 2008 that one of his employees in Africa was Lawrence Devlin, a former CIA station chief in Congo. Devlin, while working for Tempelsman, continued to provide information to the agency—a striking example of the porous boundary between intelligence work and corporate activity in Cold War Africa.

As chairman of organizations such as the Africa America Institute and the Corporate Council on Africa, Tempelsman burnished his reputation as a patron of African development. But even in these roles, questions lingered about where philanthropy ended and strategic self-interest began.

For the American public, Tempelsman’s name entered the household lexicon not through diamonds or Africa, but through his relationship with Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. They had first met in the late 1950s, when Senator Kennedy sought an introduction to the South African diamond industry. Tempelsman, already influential in African resource markets, arranged the meeting. Their paths crossed intermittently for years, including a 1960 session at the Carlyle Hotel with President-elect Kennedy and De Beers chairman Harry Oppenheimer.

But it was only after Jacqueline was widowed for the second time, following the death of Aristotle Onassis in 1975, that her relationship with Tempelsman deepened. By the 1980s, he had become not only her confidant but her financial adviser, reportedly quadrupling the $26 million inheritance she received from Onassis.

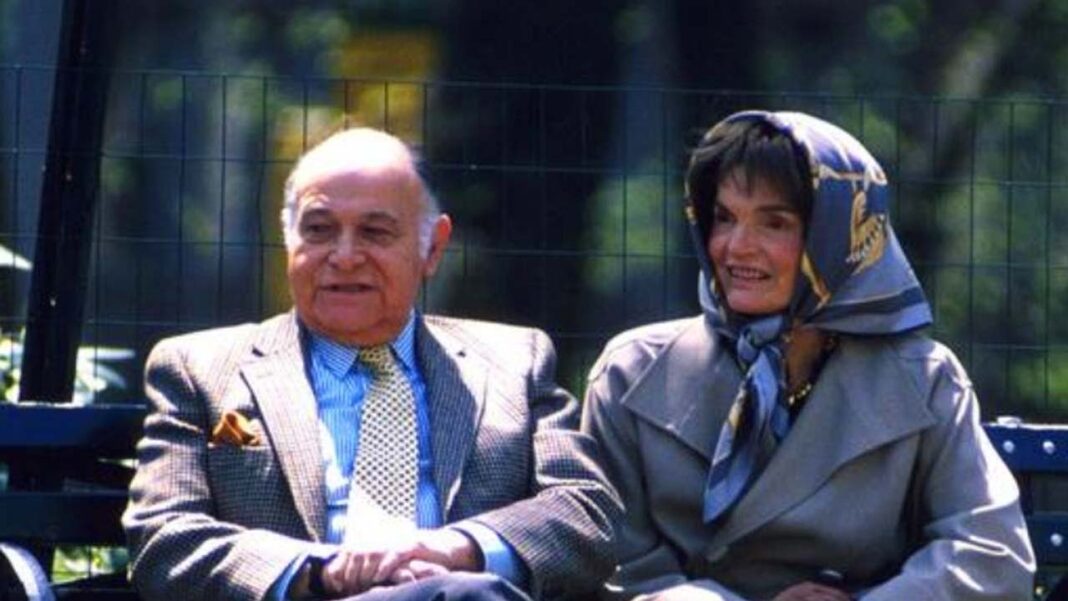

As The New York Times recalled in its obituary, the couple lived together in her Fifth Avenue apartment and were often seen at the opera, the ballet, or walking discreetly through Central Park. They entertained world leaders, including President Bill Clinton and First Lady Hillary Clinton aboard Tempelsman’s yacht, the Relemar. Friends noted their shared love of French, art, and intellectual pursuits.

When Jacqueline Onassis was diagnosed with cancer in 1993, Tempelsman moved his office into her apartment and accompanied her to the hospital. He was by her side when she died in May 1994 at the age of 64. At her funeral, he delivered a reading of C.P. Cavafy’s poem Ithaka, an ode to life’s journey.

Roger Wilkins, the journalist and civil rights figure, later told The Washington Post that it was “terrific” to know Mrs. Onassis “was with somebody who was a good, generous and gentle man.” The New York Times, in its reflections on their relationship, underscored the discretion and dignity with which both Tempelsman and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis managed their companionship.

Tempelsman’s business career was marked by his ascent to the upper echelons of the diamond trade. In 1984, he became chief executive of Lazare Kaplan International, one of the largest importers and cutters of diamonds, supplying luxury brands like Tiffany’s and Cartier. He remained a general partner in Leon Tempelsman & Son, diversifying into mining, agriculture, and other ventures.

As one of only 160 global De Beers “sightholders,” Tempelsman had access to direct diamond purchases from the cartel that maintained a near-monopoly on world supply. This privileged position cemented his wealth and influence in an industry famed for secrecy.

Beyond diamonds, Tempelsman leveraged his networks to champion causes like public health. He chaired the international advisory council of the Harvard AIDS Institute, helping to connect scientists, politicians, and philanthropists in the fight against the epidemic. “The important thing is to mobilize the different parties that can make contributions,” he told The New York Times. “Each of them lives in a different universe.”

While business defined his fortune, philanthropy broadened his profile. Tempelsman was active in Jewish causes, international development efforts, and U.S. political fundraising. He played a visible role in supporting Nelson Mandela’s first U.S. visit after his release from prison in 1990. His involvement reflected the duality of his public image: a man whose fortunes were made in countries like Zaire, but who also invested in fostering African liberation and health initiatives.

As The New York Times report pointed out, Tempelsman’s philanthropy was not devoid of strategic calculation. Just as his business depended on cultivating trust among volatile political actors, his charitable giving often reinforced networks of influence that proved useful in commerce and politics alike.

Courtly, urbane, and intensely private, Tempelsman avoided the limelight whenever possible. His reticence was so pronounced that interviews with him were rare. “I hate to deflate the romance,” he remarked to Insight in 1991. “But the reality is a lot more pedestrian.”

Yet, his presence was inescapable: accompanying Jacqueline Onassis in Central Park, at her side during her illness, and later as a fixture in Democratic Party fundraising circles. Despite gossip columns chronicling every detail of Mrs. Onassis’s life, their relationship largely escaped scandal or intrusion. As The New York Times report emphasized, public opinion seemed to coalesce around the belief that Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, after decades of tragedy and scrutiny, deserved happiness and privacy.

Maurice Tempelsman’s life encapsulated the contradictions of a global elite operating in the shadows of power. He was at once a refugee and an insider, a philanthropist and a beneficiary of autocratic regimes, a man who prized discretion yet shared the world stage with one of history’s most iconic women.

In Africa, he was both a patron of liberation and a beneficiary of kleptocracy. In America, he was both a power broker in Democratic politics and a figure of mystery, elusive to the press but central to elite circles. The New York Times, which covered his life and career for decades, often portrayed him as emblematic of the delicate, sometimes troubling intersections of commerce, politics, and intimacy.

His survivors include his children Rena, Leon, and Marcy; six grandchildren; and seven great-grandchildren.

The story of Maurice Tempelsman is, in many ways, the story of the 20th century itself: a tale of exile, ambition, resource wealth, Cold War maneuvering, and elite companionship. His life bridged Antwerp’s Jewish refugee community, the diamond mines of Africa, the corridors of Washington, and the salons of New York’s Upper East Side.

As The New York Times remarked in one of its many profiles of him, Tempelsman was always “intensely private yet unmistakably public,” a man whose influence was exerted quietly but whose impact was undeniably vast. His death closes the chapter on a remarkable, controversial, and deeply complex life—a life lived at the heart of history’s glittering and shadowy intersections.