|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Sara Menucha Peltz

Ovadia the Convert is a fascinating personality. A former member of the Christian clergy, he traveled to the Islamic lands, where he was able to convert to Judaism and study Torah. A witness to the murderous crusades, he became an accomplished scholar, who composed several liturgical poems. His life story and literary contributions have been preserved, in part, in the Cairo Genizah.

A Puzzling Piece of Papyrus

Elkan Nathan Adler was puzzled. As the first European to enter the Cairo Genizah, he was in possession of a huge and extremely rare collection: 25,000 ancient manuscript fragments. One of those fragments appeared to be a strange “marriage” between the Jewish and Christian worlds. It was a beautifully composed elegy for Moses, titled “Mi Al Har Chorev,” composed of six rhyming couplets, written in perfect, elegant Hebrew letters. Adler supposed that it had been written for the holiday of Shavuot or perhaps Simchat Torah. But above each delicately inscribed line, hovered musical notation that obviously originated from the Italian Church.

Adler dispatched the fragment to the Benedictine fathers of Quarr Abbey, situated on the Isle of Wight off the coast of Britain. Perhaps they would be able to identify the notation and shed some light on the rare find. The priests’ decisive response arrived during April 1918: The music notes were Lombardic style neumes (predecessors of today’s notes and staves) used by European Christians in the late 12th and early 13th centuries.

Compounding the mystery was the fact that the style of the Hebrew lettering could not be attributed to any location in Europe. Moreover, the paper itself was thick, slightly tan, and clearly Egyptian—a type used in many Genizah manuscripts of the 12th century.

The manuscript fragment was considered a rare treasure, puzzling scholars and students for decades. In 1947, famed musicologist Eric Werner examined it, and made a highly accurate transcription of the neumes:

Its style is closely akin to that of the Gregorian plainsong Church, if we disregard one or two embellishments which seem alien to Gregorian style … Of course, the fact that our manuscript is so similar to Gregorian tunes is not surprising since it is today proved beyond any … doubt that the root of Gregorianism lies in the music of Palestine and Syria …

He then quoted a catholic musicologist, Father Dechevrens:

Gregorian chant is the music of the Hebrews, and there is for the totality of the Roman Catholic melodies but one modal system – not that of the Greeks, but of the sacred nation of the Hebrews.

In short, both Werner and Dechevrens admit that it is not so strange to see church notations associated with a clearly Jewish piyyut (poem), as their original source was the “sacred nation of the Hebrews” to begin with. He almost seems to imply that the fragment proved that Gregorian chant, although used in the church still today, was applied to Jewish piyyutim and sung in synagogues during the middle-ages, independent of any Christian influence.

But there is a more powerful, likely explanation for the odd manuscript, which lies with its author.

In November 1964, Professor Norman Golb made a tremendous discovery. He took it into his head to compare the handwriting of the mysterious piyyut with that of another piece of parchment from the Genizah. It matched. The author of both fragments was a Jewish convert named Ovadia HaGer (Ovadia the convert), formerly Johannes of Opiddo.1

An Unlikely Inspiration

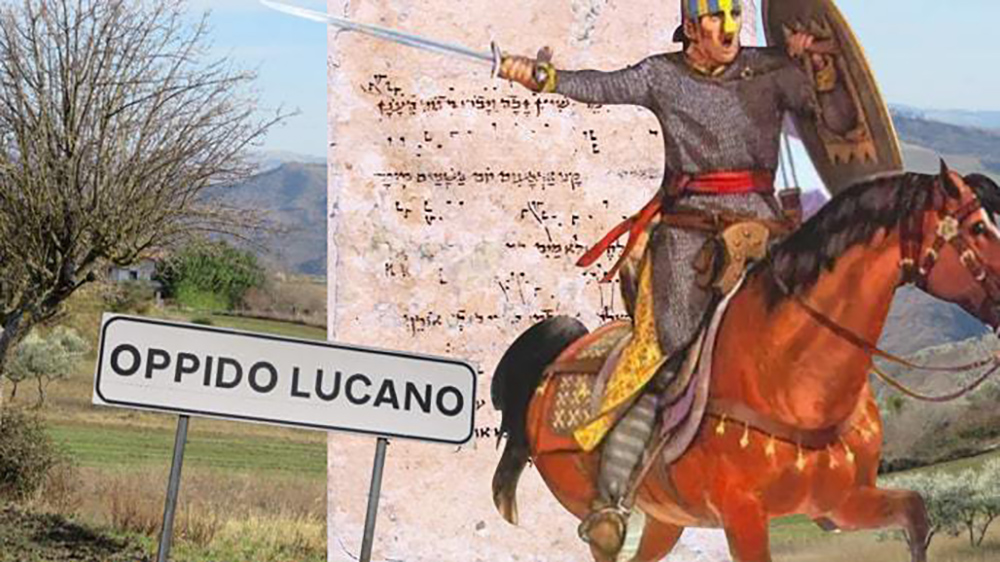

In approximately 1070, twin boys were born to Dreux and Maria, residents of Oppido Lucano, Italy. They named the elder Rogerius and the younger Johannes. Dreux was a Norman nobleman, and Rogerius, as the scion of the household, was sent to learn the arts of war and chivalry. His younger brother was designated as the family scholar and sent to study priesthood.

While still a young child, Johannes heard of a mind-boggling occurrence: The Archbishop of Bari (a Roman Catholic archdiocese in southern Italy), Andreas, had converted to Judaism. The high-profile proselyte didn’t only send shockwaves through the mind of the youngster; a range of Church officials of varying strands of Christianity were also astonished. Johannes writes in his memoirs (the primary source of this information) that, “The Greek sages and the sages of Rome were ashamed when they heard the report about him.”

Andreas had left Bari, forsaking his homeland, his priesthood, his following, and his glory, and headed to Islamic Constantinople (Istanbul) where he underwent a brit milah (circumcision). His life from that day onward was dogged with hardship—particularly non-Jews who pursued him with violent intent—but G‑d consistently saved him from their designs. He was pursued not only because he had brought dishonor upon the Church, but also likely because of the large number of non-Jews who converted following his example.

Andreas eventually left Constantinople and journeyed to Egypt where he lived out the rest of his days.2

Shortly after hearing of the extraordinary events concerning the Archbishop, young Johannes had a strange dream. He envisioned himself serving as a priest in Oppido when he saw a man standing to his right, opposite the altar. The man in his dream called his name, “Johannes!” What the vision subsequently said has been lost to history, as the fragment found in the Cairo Genizah was torn. It is safe to conclude, however, that it had something to do with the previous account of Andreas that Johannes recorded. Possibly, the man commanded him to become a Jew as well.

Nevertheless, it was 20 years before Johannes himself converted to Judaism. How he spent that time remains a mystery. It is assumed that he furthered his studies in the Church.

A Crusade Against Judaism

The next fragment of Johannes’ memoirs discusses the first crusade. He was approximately 30 years old at the time.

He describes an eclipse which took place in February of 1095 or 1096 as being an important omen for the evil to come. He quotes the prophet Joel:

The sun shall turn into darkness and the moon into blood before the arrival of the great and awesome day of the L‑rd.3

He describes the Frankish soldiers questioning among themselves why they bothered to travel to Jerusalem to fight their enemies, while their own hometowns harbored heretical foes. This kind of sentiment was what spurred the anti-Jewish actions of crusaders. Golb writes, “It is clear that he knew of the persecutions and possibly was a witness to some of them.”

A few years later, Johannes converted to Judaism, assuming the name Ovadiah. He probably chose the name Ovadiah because Ovadiah the Prophet was said to have been a Jewish convert from Edom.4 His inspiration to embrace Judaism seems to have been a combination of Andreas’s example and his own long-term immersion in the false teachings of the Church.

To be Continued Next Week

Sara Peltz is a course launch strategist and copywriter based in the UK. She’s also a private Jewish history enthusiast and occasionally burrows into her research cave and surprises the world with interesting articles like this one. Adapted from Kankan Journal.