|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Fern Sidman

In the febrile climate of contemporary discourse on the Middle East, where the vocabulary of resistance and the lexicon of terror are often contested with ferocious intensity, a dispute has erupted on the campus of the City University of New York that has reverberated far beyond the seminar rooms in which it was conceived. On Wednesday, Ambassador Ofir Akunis, the Consul General of Israel in New York, dispatched a sharply worded letter to the president of CUNY and to the chancellor of the university system, demanding the cancellation of an event entitled “The Underground in Gaza,” scheduled to take place in early March. The intervention, framed in the language of moral urgency and institutional responsibility, has cast a searching light upon the uneasy boundary between freedom of expression and what Akunis describes as the normalization of terror within a respected academic institution.

View this post on Instagram

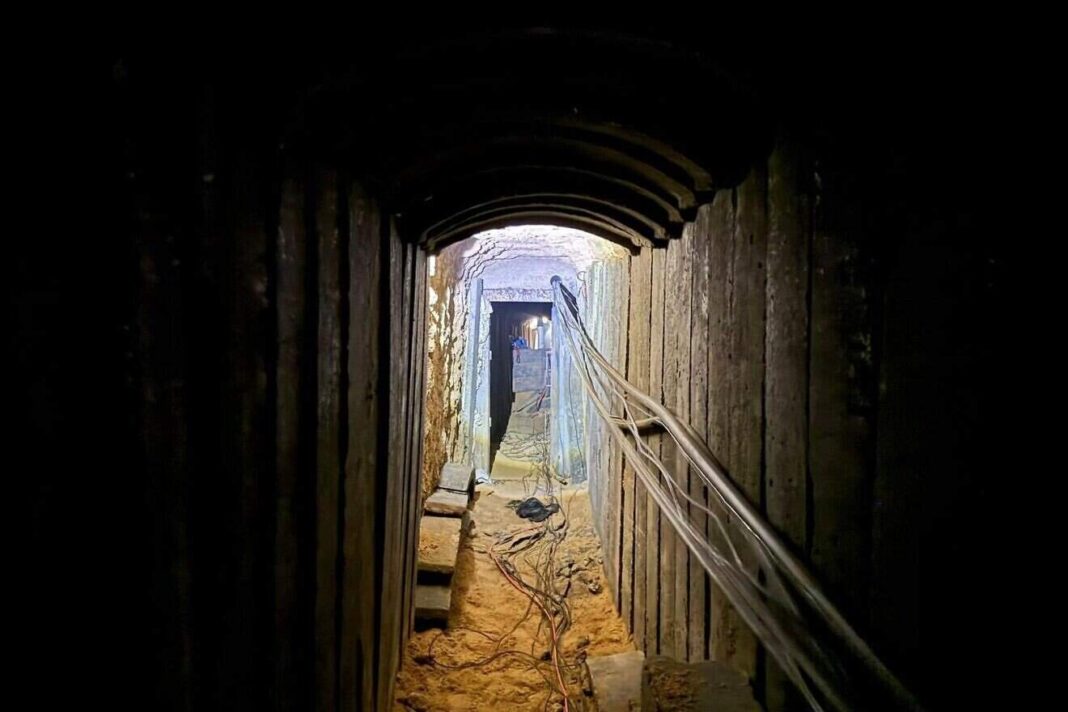

At the heart of the controversy lies the symbolic and political freight of Gaza’s subterranean tunnel network, a phenomenon that, in Akunis’s telling, cannot be disentangled from the violent history of Hamas. In his letter, the Israeli diplomat articulated a profound unease with the framing of the planned event, which he said presented the terror tunnels in Gaza “in a positive light and as a legitimate struggle.” Such a portrayal, he argued, risks sanitizing an infrastructure that has been employed not as a neutral feat of engineering or an abstract emblem of resistance, but as a practical apparatus of violence. These tunnels, Akunis wrote, are integral to the underground architecture of Hamas and have been used to carry out murders, kidnappings, and brutal attacks against innocent civilians.

The ambassador’s letter situates his objections within the legal and moral frameworks that govern public life in the United States. Hamas, he reminded the university leadership, is a designated terrorist organization under U.S. law. An event that valorizes or legitimizes elements of Hamas’s operational infrastructure thus crosses from the realm of critical inquiry into the territory of promotion and support for reprehensible actions. The charge is not merely rhetorical. It invokes the weight of legal classification and the ethical stigma attached to organizations whose tactics are defined by the deliberate targeting of civilians. By anchoring his argument in this designation, Akunis seeks to elevate the dispute from a question of taste or political disagreement to one of institutional complicity in the normalization of violence.

Yet the letter is careful to acknowledge, at least in principle, the sanctity of free expression. “I am a strong believer in freedom of expression,” Akunis wrote, signaling an awareness of the sensitivities that attend any attempt by a foreign diplomat to influence programming at an American university. The invocation of free speech is not perfunctory. It is an attempt to preempt the familiar rejoinder that universities must serve as arenas for the contestation of ideas, including those that offend or unsettle. But Akunis draws a sharp boundary: support for a murderous terrorist organization, he contends, does not fall within the ambit of protected expression, particularly when it is given a platform by a public institution with a reputation to uphold.

This distinction between expression and endorsement lies at the core of the present controversy. Universities have long defended their role as spaces in which controversial subjects may be examined, dissected, and debated without fear of censorship. Yet Akunis’s intervention challenges the assumption that all forms of representation are morally equivalent within an academic context. To present the tunnels of Gaza as a “legitimate struggle,” he argues, is not to analyze a phenomenon but to imbue it with normative approval. In this reading, the event’s framing collapses the critical distance that distinguishes scholarship from advocacy, and in doing so, it risks transforming the university into a stage upon which terror is aestheticized.

The language of the letter grows more severe as it moves from legal designation to moral condemnation. “Support for such an event constitutes the normalization of terror and crosses a moral red line,” Akunis wrote. The phrase “moral red line” is not chosen lightly. It evokes a threshold beyond which toleration becomes complicity, and beyond which the university’s commitment to pluralism curdles into an abdication of ethical responsibility. The metaphor of normalization is particularly potent. To normalize terror is to render it banal, to strip it of its moral shock, and to permit its logic to seep into the fabric of ordinary discourse. In Akunis’s view, the danger lies not only in the specific content of the event but in the broader cultural signal it sends: that the instruments of terror can be reframed as legitimate expressions of struggle within the halls of academia.

Perhaps the most emotionally charged dimension of the letter concerns the safety and well-being of Jewish students. Akunis writes that for many Jewish students, the glorification of Hamas is not an abstract political gesture but an antisemitic and hostile act, one that resonates with a long history of persecution and violence. In this formulation, the event is not merely controversial; it is potentially traumatizing. The university, he insists, bears a responsibility to ensure that all students can participate in academic life without intimidation or harassment. The invocation of safety shifts the terrain of the debate from the abstract plane of free speech to the concrete realities of campus life, where the boundaries between expression and intimidation are often contested and where the impact of symbolic acts is felt in personal terms.

The ambassador’s concern reflects a broader anxiety about the climate on university campuses, where debates over Israel-Palestine, and the conduct of armed groups frequently generate intense polarization. For Jewish students, the perception that an institution has provided a platform for what they experience as the glorification of a group committed to violence against Israelis can engender a sense of isolation and vulnerability. Akunis’s letter implicitly challenges university administrators to consider not only the formal legality of hosting such an event but also its experiential consequences for members of their community. The responsibility of the academic institution, in his formulation, is not limited to the facilitation of debate; it extends to the cultivation of an environment in which students are not subjected to what they perceive as the legitimization of violence against their own people.

The demands articulated in the letter are unequivocal. Akunis calls for the immediate cancellation of the event, a public condemnation of the initiative, and a clear commitment by the university to ensuring the safety of Jewish students on campus. These demands, taken together, amount to a call for institutional repudiation, not merely quiet withdrawal. The insistence on a public condemnation suggests that the ambassador seeks not only to prevent the occurrence of the event but to establish a normative boundary, a public declaration that certain forms of representation are incompatible with the values of the university.

The implications of this episode extend beyond the particularities of one event and one institution. It raises enduring questions about the role of universities in adjudicating the moral dimensions of controversial political content. Are institutions of higher learning merely neutral platforms upon which ideas may be aired, or do they bear a responsibility to police the ethical contours of the discourse they host? Akunis’s letter argues forcefully for the latter, contending that neutrality in the face of what he characterizes as the normalization of terror is itself a moral failure.

At the same time, the controversy exposes the tension inherent in the modern university’s self-conception. Academic freedom has long been defended as a bulwark against political interference, a principle that safeguards the capacity of scholars and students to explore uncomfortable truths. Yet the invocation of terrorism and the lived fears of targeted communities complicate this narrative. When does critical engagement with violent movements become an act of legitimation? When does the language of resistance shade into the rhetoric of apology for brutality? These are not questions that admit of easy answers, and the dispute at CUNY underscores the fragility of the equilibrium universities seek to maintain between openness and responsibility.

In the coming days, the response of CUNY’s leadership will be scrutinized not only by the Israeli diplomatic mission but by a wider public attuned to the cultural battles that play out on university campuses. The outcome will signal how one of the nation’s largest public university systems understands its obligations to free expression, to the safety of its students, and to the moral boundaries of the discourse it sponsors. In challenging “The Underground in Gaza,” Ambassador Akunis has forced the institution to confront a question that lies beneath the surface of academic life: where, in the labyrinthine tunnels of ideas, does critique end and complicity begin?