|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

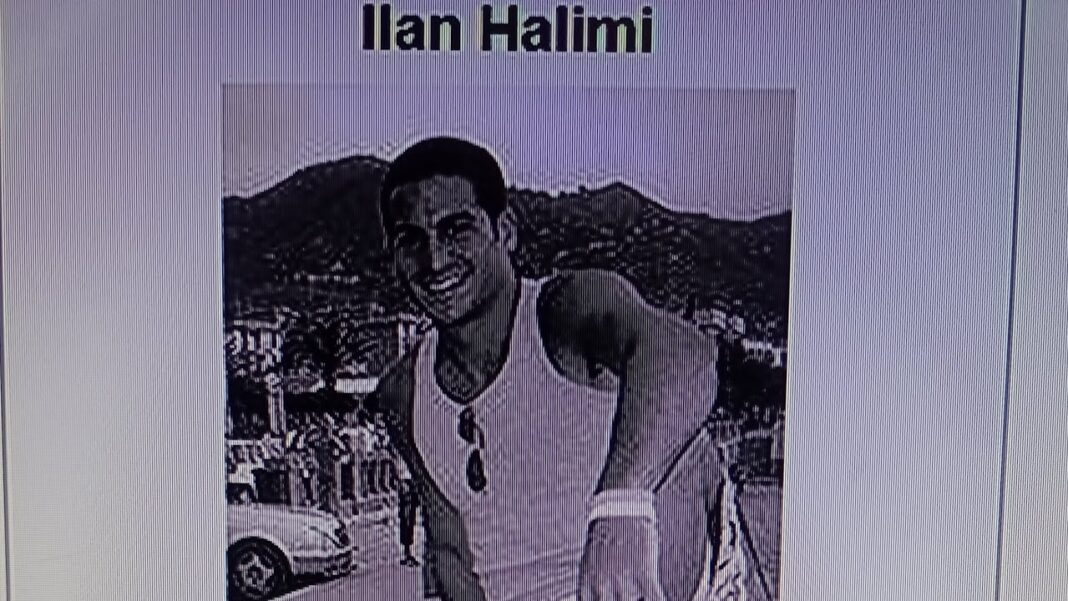

By: Fern Sidman

Twenty years after the brutal murder of Ilan Halimi, France’s Jewish community finds itself mourning not only a life lost to barbaric antisemitic violence, but also the repeated desecration of his memory amid a disturbing resurgence of hatred targeting Jews and Israelis across the country. As The Algemeiner reported on Tuesday, the anniversary of Halimi’s death has become a grim barometer of the state of antisemitism in modern France—an indicator that, despite decades of promises and memorials, the poison that killed him has not been eradicated.

On Tuesday, Jewish institutions across France marked two decades since Halimi’s death with ceremonies intended to honor his memory and reaffirm communal resilience. Yet these commemorations were overshadowed by the latest act of vandalism at a site dedicated to him: another olive tree, planted as a living symbol of remembrance, was deliberately cut down. For many French Jews, the act felt less like random vandalism and more like a chilling message—that even remembrance itself is under attack.

“Twenty years on, Ilan Halimi’s memory still needs to be protected and honored, yet it continues to come under attack,” the Representative Council of Jewish Institutions of France wrote in a statement cited in The Algemeiner report. The organization, known by its French acronym CRIF, described the vandalism as emblematic of a broader and deeply entrenched problem. “Antisemitism remains a persistent threat in France today,” the statement warned, underscoring fears long expressed by Jewish leaders and echoed in reporting by The Algemeiner over recent years.

Halimi’s murder in 2006 marked a watershed moment in French history. Abducted in January of that year by a gang of approximately 20 individuals from a low-income housing estate in Bagneux, a Paris suburb, Halimi was targeted solely because he was Jewish. His captors believed, grotesquely and falsely, that “the Jews have money” and that his family could be coerced into paying a large ransom.

For three weeks, Halimi was held captive, tortured relentlessly, burned, beaten, and humiliated. When he was finally found in Essonne, south of Paris, he was naked, gagged, and handcuffed near a railway track, his body bearing unmistakable signs of sustained torture. He died en route to the hospital. He was 23 years old.

As The Algemeiner has noted in numerous retrospectives, the murder shocked France not only for its cruelty but also for the initial reluctance of authorities to recognize it as an antisemitic crime. That hesitation—later acknowledged as a failure—left a lasting scar on the relationship between French Jews and the state institutions charged with protecting them.

In 2011, French authorities planted the first olive tree in Halimi’s memory, a gesture intended to symbolize peace, endurance, and reconciliation. Since then, olive trees have become the primary memorial markers honoring Halimi at various sites connected to his life and death. Yet these symbols have themselves become targets.

Last week’s vandalism was not an isolated incident. As The Algemeiner reported, a plaque honoring Halimi in the southeastern town of Cagnes-sur-Mer was recently defaced, prompting an investigation for “destruction and antisemitic damage.” In that case, a 29-year-old man with no prior criminal record was arrested. Although he admitted to the act, he denied antisemitic intent and is now awaiting trial—a familiar refrain in cases that Jewish organizations argue are too often minimized or euphemized.

In 2024, another olive tree planted in Halimi’s memory was cut down in Épinay-sur-Seine, a suburb north of Paris. Two Tunisian twin brothers were arrested and convicted for the act, but notably acquitted of antisemitism charges. Both were sentenced to eight months in prison, with one receiving a suspended sentence. According to local media cited by The Algemeiner, one of the brothers has since been deported from France.

For Jewish leaders, these repeated attacks form a pattern that cannot be ignored. Memorials, they argue, are not merely symbolic objects; they are statements of collective memory and moral clarity. Their destruction represents an attempt to erase not just a person, but the lessons his death should have taught society.

French Interior Minister Laurent Nunez responded forcefully to the most recent vandalism. “We will bring those responsible to justice,” he wrote in a post on X, pledging unwavering determination to combat antisemitic and anti-religious acts. His words noted the government’s effort to project resolve at a moment of acute tension.

“Our collective outrage is matched only by our unwavering determination,” Nunez added, framing the act as an affront not only to the Jewish community but to the values of the Republic itself.

Yet for many French Jews, such statements ring hollow without sustained results. As The Algemeiner has chronicled, antisemitic incidents in France have surged dramatically in recent years, particularly since the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war. Jewish schools, synagogues, businesses, and individuals have been targeted with threats, vandalism, and violence, prompting fears that the country’s once-proud claim to republican universalism is fraying.

The repeated desecration of Halimi’s memorials comes at a time when antisemitism in France has reached levels unseen in decades. According to figures cited by The Algemeiner, Jewish organizations have reported a sharp rise in assaults, harassment, and property damage aimed at Jews and Jewish institutions. Much of this hostility is fueled by a toxic convergence of Islamist extremism, far-left anti-Zionism, and conspiracy-laden rhetoric proliferating online.

In this climate, Halimi’s murder has taken on renewed significance. He is no longer remembered only as a victim of a single horrific crime, but as a symbol of the vulnerability many Jews still feel in France. The attacks on his memorials, activists argue, are attempts to normalize antisemitism by targeting even the most unambiguous victim of hatred.

CRIF has emphasized that honoring Halimi is not solely a Jewish concern, but a national obligation. “Protecting his memory,” the organization has argued in statements referenced by The Algemeiner, “is inseparable from protecting the Republic’s commitment to equality and justice.”

Despite the repeated vandalism, French authorities and Jewish organizations have persisted in replanting trees and restoring memorials. Each act of restoration is intended as a form of resistance—a declaration that remembrance will not be surrendered to hatred.

In Essonne, where Halimi was found dying, two other olive trees planted in his honor were vandalized in 2019. Each time, they were replaced. For those involved in these efforts, the cycle of destruction and renewal has become a grim ritual, but also a testament to resilience.

As The Algemeiner report observed, the persistence of these memorials reflects a broader determination within France’s Jewish community to assert visibility and dignity in the face of intimidation. It is a refusal to allow antisemitism to dictate whose stories are remembered and whose are erased.

Two decades after Ilan Halimi’s murder, France continues to grapple with the implications of his death. While legal reforms and public awareness have improved since 2006, the resurgence of antisemitic acts suggests that deeper societal currents remain unaddressed.

For Jewish leaders, educators, and activists interviewed by The Algemeiner, the lesson of Halimi’s story is painfully clear: remembrance without vigilance is insufficient. Memorials must be protected not only physically, but culturally—through education, enforcement of the law, and an unambiguous rejection of antisemitism in all its forms.

As France reflects on the 20th anniversary of Halimi’s death, the question confronting the nation is stark. Will his memory finally be secured as a warning heeded, or will it remain a battleground in a society still struggling to confront its oldest hatred?

For now, as another olive tree is replanted and another investigation unfolds, Ilan Halimi’s name continues to echo—not only as a reminder of a life brutally cut short, but as a test of France’s moral resolve in an era when that resolve is being relentlessly challenged.

French Jews need to begin training in self defense, wearing bullet proof vests and carrying all forms of legal self defense tools. Now. No more dead Jews. Jews cannot rely solely upon others to defend them, not ever, not now. Our history shows us, the more you bend over, the harder you get kicked. We need to become fierce and feared Jewish women and men. If you attack us, we will take you down and ask questions later. All places where Jews gather need 24/7 security, Jewish men and women patrolling in full legal gear, stone wall gates, surveillance, electronic barriers. Like it or not, this is our new reality. We are in survival mode if we are to continue to be Jews. Demand full Jewish Civil Rights. Demand your cities provide guards and reimburse you for those you have to hire because the world is failing to protect us now.