|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Fern Sidman – Jewish Voice News

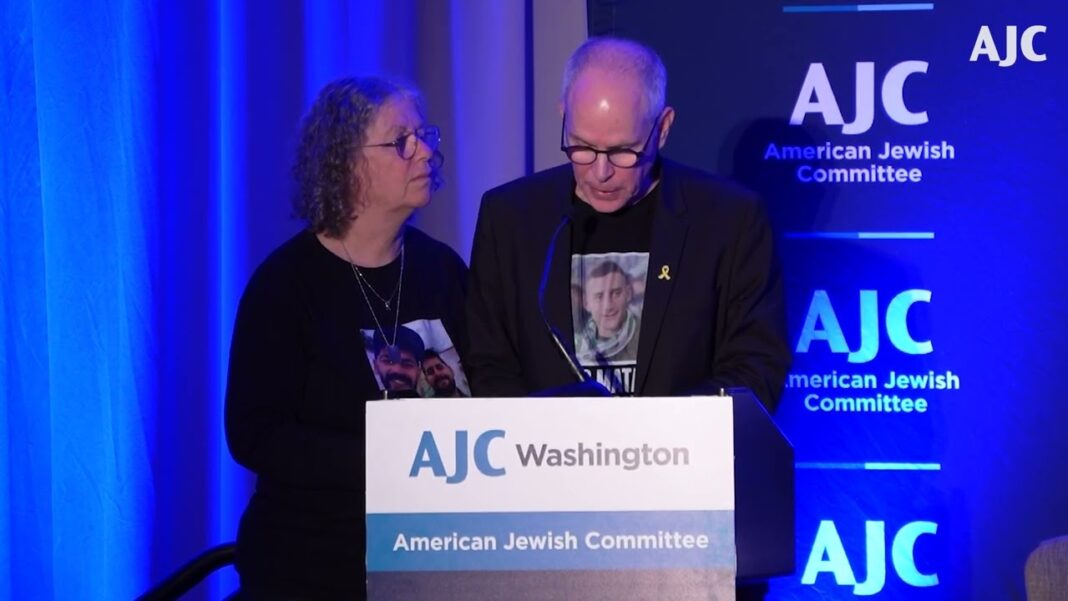

In Geneva this week, before the United Nations Committee Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT), the veil of denial surrounding Hamas’ atrocities on October 7 was torn apart once again — this time by two of the survivors themselves. Aviva and Keith Siegel, a married couple kidnapped from their home near the Gaza border, delivered heart-wrenching, meticulously detailed testimony about their seven-month ordeal in Hamas captivity.

Their statements, which The Jewish Voice and international media have described as among the most haunting public testimonies since the October 7 massacre, have shaken even seasoned diplomats at the UN. Speaking calmly but with visible trauma, both Aviva and Keith recounted scenes of calculated cruelty, humiliation, starvation, and sexual abuse.

The Siegels, both dual citizens who had lived in a small Gaza-border kibbutz, addressed the Committee as part of an Israeli delegation led by Itamar Donenfeld, Director General of Israel’s Ministry of Justice. The delegation’s purpose was to demonstrate Israel’s compliance with the Convention against Torture — and, by extension, to expose how the very principles the UN claims to uphold have been desecrated by Hamas’ conduct.

Keith Siegel, a 66-year-old retired engineer, began his testimony with the horrifying precision of a man reliving every second of his trauma.

“On October 7, at 6:29 a.m.,” he told the Committee, “we entered the MAMD [safe room]. We heard gunshots, rockets, and then the terrorists in the house. They shot at the door behind which we were hiding, then dragged us out — Aviva and I, still in our pajamas — surrounded by fifteen armed men shouting in Arabic. One of their bullets hit me in the wrist; they broke my ribs, and they tore the meniscus in Aviva’s knee.”

They were thrown into a pickup truck and driven across the border into Gaza. What awaited them there was not chaos or random brutality, Keith explained — it was organized, sadistic ritual.

He recalled being placed in a small room where a bound Israeli woman was being tortured in front of him. “A terrorist told me that I must convince her to confess that she was an IDF officer,” he said. “She was gagged, her limbs tied, and two men beat her with a metal pole. Another pressed a sharpened stick to her forehead, then put a gun to her head. They said if I did not confess, they would kill her.”

“I realized then,” he said quietly, “that they controlled me entirely. Every act of theirs was designed to strip us of humanity and turn fear into obedience.”

Keith’s voice broke when he described the months that followed. “For fifty days, I was with Aviva,” he said. “After she was released, I was sometimes held with other captives, sometimes in complete isolation. In total, I spent six months entirely alone — sixty-six years old, cut off from the world, terrified, not knowing whether my wife was alive.”

He continued: “For their amusement, the guards compared parts of my body with another hostage’s, laughing and mocking us. They humiliated us with knives, forced us to undress, shaved our bodies, and denied us access to a toilet until we could no longer control ourselves.”

Keith was starved and dehydrated, denied even basic hygiene. “Every basic human right was stripped away,” he said. “More than once, I was forced to strip naked as they laughed. They would film me. They deprived me of water and food. I begged to drink from the same tap where they washed their hands.”

He recounted that he spent endless nights praying, imagining the day he would see his mother again. “I dreamed of visiting her the moment I returned,” he said. “But when I finally came home by helicopter, the first thing I asked Aviva was, ‘How is my mother?’ She had died two months earlier. She never knew I came back. I never got to say goodbye.”

If Keith’s testimony illuminated the psychological torture of captivity, Aviva’s exposed its monstrous physicality. Her voice trembled but never faltered as she spoke of watching her captors’ cruelty unfold in Gaza’s underground tunnels.

“When we were taken below ground,” she began, “there was a boy from my community — sixteen years old. His hands were tied with plastic cuffs. He was bleeding heavily. When one of the terrorists came to cut the cuffs with a cutter, he sliced the boy’s hand instead. He did it on purpose. I just wanted to scream. I saw the terrorist smiling as he did it.”

“For fifty-one days,” Aviva said, “I was certain I was going to die.” She described losing ten kilograms from starvation, hiding morsels of food to save for her husband. “They starved us,” she said, “while they ate in front of us, chewing deliberately, laughing. We begged for water, but what we received was contaminated. I suffered from stomach pain and diarrhea the entire time.”

The psychological cruelty, she said, was matched only by the sexual degradation she witnessed. “One day, a young woman came out of the shower trembling,” Aviva said. “I was not allowed to hug her, but I did anyway. Later she whispered that one of the terrorists had touched her — had done whatever he wanted.”

Another young girl, just sixteen, was forced to shower under the gaze of an armed guard. “She had never even shown her body to anyone,” Aviva said through tears. “The terrorist just stood there and smiled.”

She spoke, too, of a captive woman forced to perform oral sex on her captor — then ordered to smile afterward. “The worst part,” she said, “was watching and being unable to help, unable even to cry. I tried to hold onto my humanity — to remember I was still a person.”

Aviva described a regime of absolute control. “They forced us to lie down from 5:00 p.m. until 9:00 a.m.,” she said. “We were forbidden to move. My body ached. I wanted to stretch, to sit, to scream, ‘Just let me sit for five minutes.’ But they would scream back and threaten to kill me. One night, I moved my foot out from under a blanket, and a terrorist screamed that I was forbidden to do that. It sounds small, but that was the level of domination they imposed — over every movement, every breath.”

Her account painted a portrait of captivity as psychological disintegration. “We were not people to them,” she said. “We were trophies, property, symbols to be used for their joy and their propaganda.”

At one point in her testimony, Aviva turned to the larger horror that befell her community. Her tone hardened. “I come from a kibbutz where sixty-four people were murdered,” she said. “Forty families lost at least one family member. People died slowly, talking to their loved ones on the phone, saying goodbye as they were burned alive or shot. Hamas documented everything because they were proud.”

Then came words that left the Geneva hall in stunned silence. “They played soccer with human heads,” she said. “They cut off girls’ breasts and played with them. One of the boys from my community was buried without his head — it was found later in Gaza, in a freezer with ice cream.”

Her voice wavered as she recalled returning home with an elderly captive named Alma, aged eighty-four. “She had lost half her body weight. She was given two dates a day. When we arrived, her body temperature was twenty-eight degrees Celsius. The doctor said that if I had not massaged her during the journey, she would have died. She survived. I am thankful for that — and thankful that Keith came home alive.”

Following the Siegels’ testimony, Itamar Donenfeld, head of Israel’s Ministry of Justice, addressed the Committee with restrained fury. “What we have heard today,” he said, “are not merely personal accounts — they are a moral and legal indictment of global silence.”

He reminded the Committee that Israel remains one of the few nations under constant terrorist assault while being held to the highest standards of humanitarian law. “The State of Israel is fully committed to the principles of the Convention for the Prevention of Torture,” he said, “but that commitment cannot be unilateral. The silence of the international community in the face of kidnapping, torture, and sexual abuse is itself a violation of this Convention’s spirit.”

“The Convention must not remain a document,” Donenfeld declared. “It must be a moral compass — one that demands action.”

The Israeli delegation — composed of officials from the Ministries of Justice, Foreign Affairs, and National Security, as well as the Israel Police, Prison Service, and Military Prosecutor’s Office — underscored Israel’s ongoing cooperation with UN mechanisms, even amid a climate of persistent bias. As Israel’s representatives pointed out, this very hearing was part of the process of implementing Israel’s sixth periodic report under the Torture Convention, submitted to the Committee in 2020 — a testament to Israel’s continued adherence to international law despite being targeted by terror.

While the Siegels’ testimonies dominated headlines, a quieter story unfolded back home. Omri Miran, another former hostage, returned this week to his kibbutz in Nahal Oz — 768 days after his abduction. His wife, Lishi-Miran Lavie, shared her thoughts on social media:

“Rubbing my eyes and still trying to digest that this is real,” she wrote. “768 days later, Omri is in Nahal Oz again. Walking along the kibbutz paths, smiling and laughing. The last time he was here, it was the darkest day of our lives.”

She described how she had refused to renovate their home during his captivity, leaving bullet holes in the walls, shattered glass on the floor, laundry unfolded — a shrine to waiting. “I couldn’t change anything,” she said. “Renovating would have felt like admitting it was okay.”

Now, she wrote, “the memories of crying and anxiety are being replaced by smiles and thoughts of the future. We know the road is long, but we are finally on it.”

Her words resonated deeply with those still waiting for their loved ones’ return — a reminder that, for hundreds of Israeli families, the agony of captivity remains ongoing.

The Siegels’ appearance before the UN Committee was more than testimony; it was an act of defiance. Their words, raw and unembellished, transformed an international forum into a moral tribunal — not against Israel, but against indifference.

Every detail they recounted — the starvation, the sexual violence, the mutilations, the forced degradation — stands as living evidence against the notion, too often whispered in diplomatic corridors, that Hamas’ crimes can be rationalized by politics.

These were not random acts of war; they were ritualized atrocities, committed with joy, filmed with pride, and defended by silence.

For Keith and Aviva Siegel, survival is no victory. Their testimony is not vengeance; it is a plea — for truth, for memory, and for moral clarity in a world increasingly numb to horror. “We do not ask for mercy,” Keith told the Committee. “We ask only that what happened to us will never happen again.”

And in those words, stripped of bitterness, lies Israel’s deepest wound and its unyielding strength — the refusal to surrender humanity in the face of barbarism.

As the Geneva session concluded, several diplomats privately told Israeli officials that they had never before heard such unfiltered witness accounts within a UN setting. Yet the question remains whether moral outrage will translate into moral action.

The UN has long claimed to be the custodian of human dignity. The Siegels’ testimony has now placed that claim under scrutiny. The world can no longer feign ignorance of Hamas’ crimes.

As Donenfeld reminded the Committee, “This is not a political issue. It is a test of civilization itself.”

For Aviva and Keith Siegel — and for the countless others who did not return — it is a test the world can no longer afford to fail.

. . . have shaken even seasoned diplomats at the UN.

Seriously? How shaken?

I’m sure the UN will get on it right away.