|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Fern Sidman

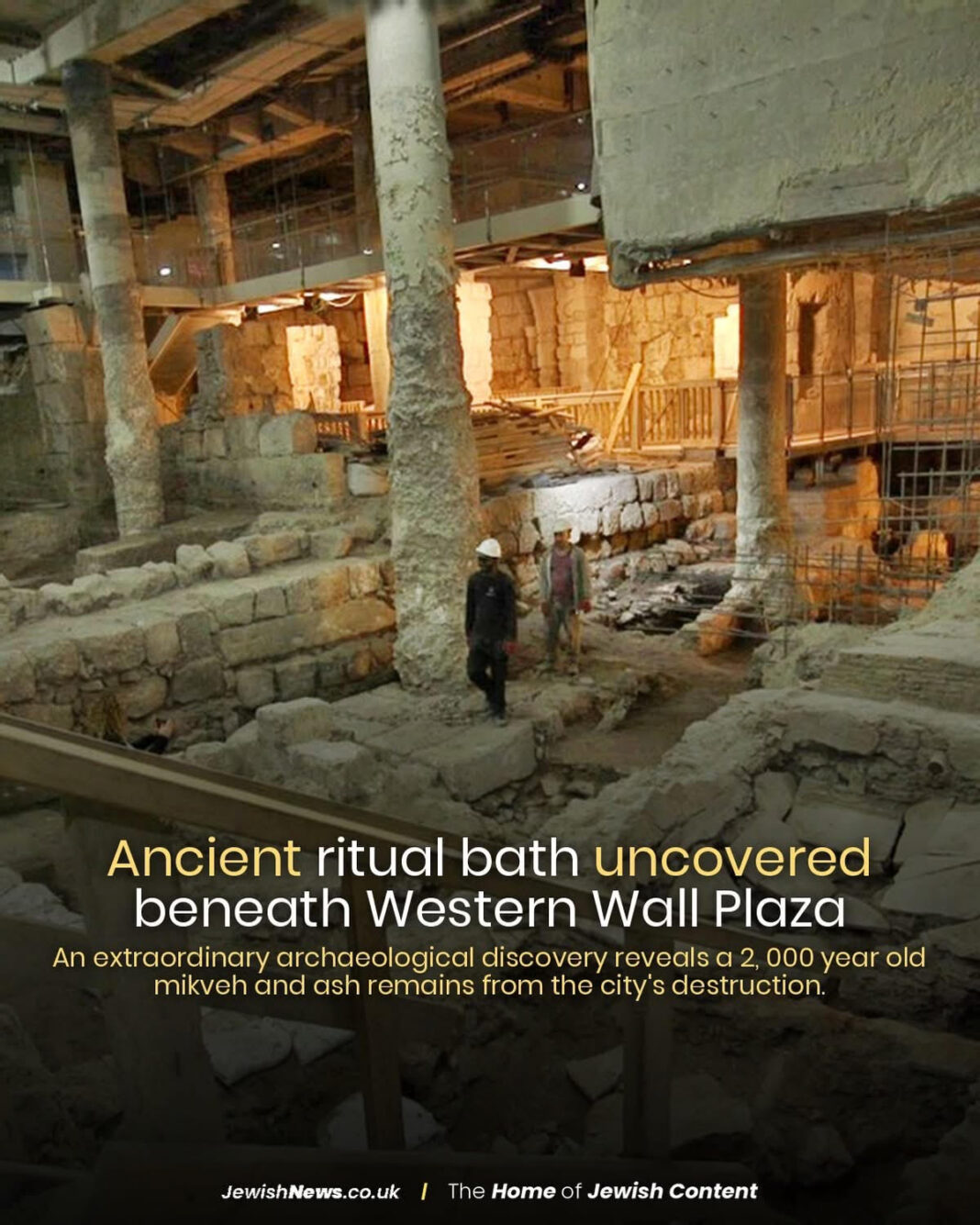

A remarkable archaeological discovery beneath Jerusalem’s Western Wall Plaza is offering an almost unbearably intimate window into the final days of the Second Temple period, unearthing not only stones and steps but the spiritual rhythm of a vanished world. As reported on Tuesday by The Jewish News of the UK, archaeologists working under the auspices of the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Western Wall Heritage Foundation have uncovered a mikveh—an ancient Jewish ritual bath—sealed beneath layers of destruction dating precisely to the Roman obliteration of Jerusalem in the year 70 CE.

This mikveh is no ordinary relic. Bearing ash remains believed to be from the catastrophic inferno that consumed the Second Temple, it stands as one of the most poignant material witnesses to the cataclysm that forever reshaped Jewish history. The Jewish News of the UK described the find as “a silent but searing testament to Jerusalem’s religious intensity at the very moment it was extinguished.”

Rectangular in shape and hewn directly into Jerusalem’s bedrock, the mikveh measures approximately 3.05 meters long, 1.35 meters wide, and 1.85 meters deep. Four carefully carved steps descend into the basin, which is lined with fine plaster—an unmistakable hallmark of Second Temple ritual architecture.

What renders this discovery extraordinary, as emphasized in The Jewish News of the UK report, is the stratigraphic context in which it was found. The mikveh lay sealed beneath a destruction layer unequivocally dated to 70 CE. Alongside it were numerous stone and pottery vessels, preserved in situ as if frozen in the very instant when Roman legions breached Jerusalem’s defenses and set the city ablaze.

For archaeologists, this is the holy grail of excavation: a ritual installation discovered exactly where and how it was used, with no later intrusions to muddy the story. The ash residues, scattered across the floor and within the fill above the mikveh, speak of firestorms that must have raged above as Jews fled or were slaughtered in the streets.

Ari Levy, the excavation director for the Israel Antiquities Authority, told The Jewish News of the UK that the discovery reinforces a fundamental truth often lost amid modern political debates: Jerusalem was, first and foremost, a Temple city.

“Many aspects of daily life were adapted to this reality,” Levy explained. “This is reflected especially in the meticulous observance of the laws of ritual impurity and purity by the city’s residents and leaders.”

In Temple-era Judaism, ritual purity was not a peripheral concern but a daily discipline. Pilgrims ascending to the Temple Mount were required to immerse themselves before entering sacred precincts, and residents living in proximity to the Temple maintained strict standards of purity as part of their spiritual routine.

The mikveh beneath the Western Wall Plaza likely served both local inhabitants and the throngs of pilgrims who arrived in Jerusalem during the pilgrimage festivals—Pesach, Shavuot, and Sukkot—when the city’s population swelled severalfold.

Among the most striking elements of the find are the stone vessels recovered alongside the mikveh. As The Jewish News of the UK report detailed, these vessels were not aesthetic choices but halakhic necessities.

Levy elaborated: “The reasons for using stone vessels are halakhic, rooted in the recognition that stone, unlike pottery and metal vessels, does not contract ritual impurity. As a result, stone vessels could be used over long periods and repeatedly.”

This insight transforms inert artifacts into living halacha. The residents of Second Temple Jerusalem were not merely compliant with ritual law—they engineered their material culture to reflect it. Stone vessels represented a kind of spiritual technology, allowing daily life to proceed without constant fear of ritual contamination.

Their presence here, adjacent to the mikveh, is almost unbearably intimate. These were not museum pieces. They were tools of devotion, abandoned in the chaos of Rome’s final assault.

The Second Temple’s destruction in 70 CE was one of the most traumatic events in Jewish history. Roman chroniclers such as Tacitus and Jewish eyewitnesses like Flavius Josephus describe a city engulfed in fire, its inhabitants massacred or enslaved, its sacred heart obliterated.

The mikveh now uncovered offers physical corroboration of these texts. The Jewish News of the UK reported that the ash residues within the excavation layer align with the known destruction horizon, providing material proof of the conflagration that accompanied the Temple’s fall.

This is not symbolic ash. It is the ash of Jerusalem’s spiritual epicenter.

One of the most far-reaching consequences of the Temple’s destruction was the transformation of Judaism itself. With sacrifices no longer possible, Jewish religious life pivoted from Temple-based worship to synagogue prayer, Torah study, and rabbinic law.

Yet, the longing for the Temple never vanished. It became encoded into Jewish liturgy, mourning practices, and collective memory. Every wedding glass shattered, every Tisha B’Av lamentation, every prayer for the rebuilding of Jerusalem echoes the trauma of 70 CE.

The mikveh’s discovery dramatizes that pivot. It captures Judaism at the precise moment before the world it sustained was extinguished.

Mordechai Eliav, director of the Western Wall Heritage Foundation, offered perhaps the most resonant interpretation of the find, telling The Jewish News of the UK that it “testifies like a thousand witnesses to the ability of the people of Israel to move from impurity to purity, from destruction to renewal.”

His words encapsulate the paradox of Jewish survival. Even in the ruins of obliteration, the artifacts of faith endure. The mikveh, once a place of spiritual cleansing, now emerges from ash as a monument to continuity.

The excavation was conducted deep beneath the Western Wall Plaza, a site visited by millions annually. Tourists and worshippers tread daily upon stones that now conceal not just architecture but the emotional geology of Jewish memory.

The Jewish News of the UK report emphasized that this find is not merely academic. It reshapes how modern Jews understand their relationship to the Wall. The Western Wall is not simply the remnant of a retaining structure; it is the surviving limb of a city that once pulsed with ritual life—life now partially restored through archaeology.

The mikveh’s discovery has resonated far beyond Israel. Jewish communities worldwide, including in Britain, have followed the story through The Jewish News of the UK, which has devoted prominent coverage to the excavation.

For British Jews, whose religious lives unfold in synagogues far removed from Jerusalem’s stones, the mikveh offers a tangible link to a shared spiritual ancestry. It reminds them that their rituals—washing hands, immersing in mikva’ot, safeguarding purity—are not abstractions but inheritances carved into bedrock.

This discovery underscores a broader truth: archaeology in Jerusalem is never merely about stones. It is about dialogue—between past and present, between text and terrain, between mourning and hope.

As The Jewish News of the UK report observed, the mikveh does not simply add a chapter to a textbook. It interrupts complacency. It insists that Jerusalem’s story is not finished, that beneath every modern layer lies a sacred palimpsest waiting to be read.

Further analysis of the mikveh, its ash deposits, and associated artifacts is ongoing. Researchers hope to learn more about the final days before the Temple’s fall, possibly identifying patterns of usage or emergency behaviors preserved in the debris.

Yet even without such refinements, the mikveh already stands as one of the most emotionally charged archaeological finds of recent decades.

This is not merely a story about what was lost—but about what remains. In the ashes of destruction, the people of Israel continue to find traces of holiness, affirming Eliav’s profound insight: that Judaism is not a religion of ruins, but of renewal.

And beneath the stones of Jerusalem, the water still waits.

This shows without a shadow of a doubt that Israel was previously, currently, and for the future, a Jewish State – not Palestinian. The world needs to learn this truth – though the nay-sayers will always doubt, the more we find through the science of archeology, the more proof we have.