|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Fern Sidman

In a revelation that reverberates through the annals of history and justice, nearly 900 previously undisclosed accounts with potential links to the Nazi regime have been uncovered at a Swiss bank, according to Senator Chuck Grassley. This startling discovery raises profound questions about the role of financial institutions in war crimes and the complicity of banks in facilitating the atrocities of the Holocaust under Adolf Hitler’s regime. As an independent investigation unfolds, led by Neil Barofsky, a seasoned American attorney, the spotlight falls on UBS, the Swiss banking giant that recently acquired Credit Suisse in an emergency takeover in 2023.

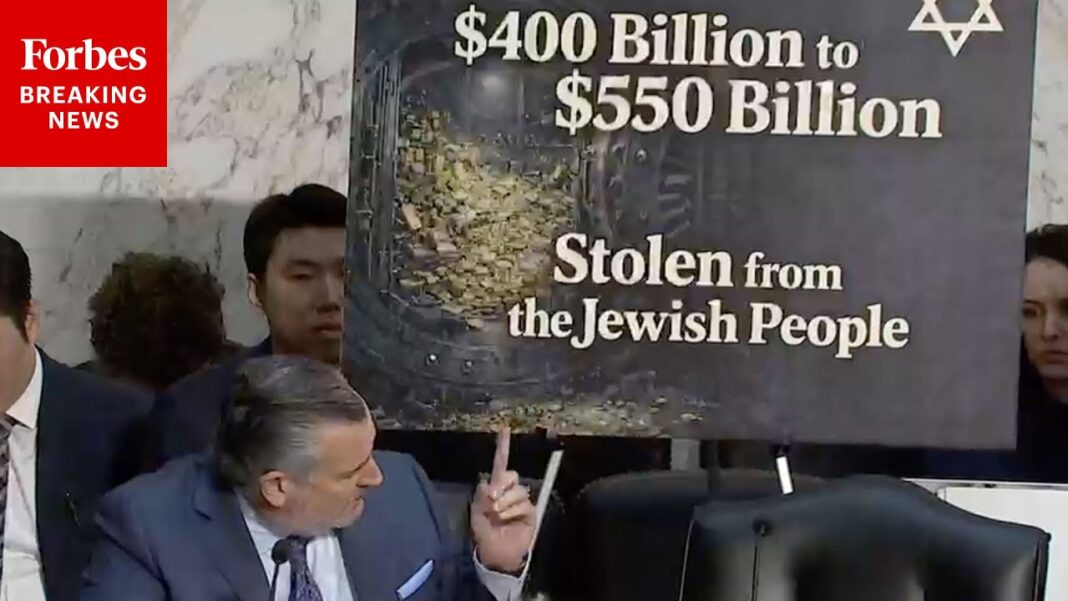

As reported on Wednesday by The Telegraph of the UK, during a Senate judiciary committee hearing on Tuesday, Senator Grassley, who chairs the committee, disclosed that the account holders included entities such as the German foreign ministry, the notorious SS paramilitary organization, and a German arms-manufacturing company—all integral components of the Nazi apparatus responsible for the Holocaust. The gravity of these findings cannot be overstated, as they suggest a systemic pattern of financial exploitation and moral negligence that allowed atrocities to persist unchecked.

Barofsky’s investigation aims not only to elucidate the depth of UBS’s complicity but also to expose the hidden mechanisms through which wealth was appropriated and transferred during one of history’s darkest epochs. During the hearing, Barofsky outlined that Credit Suisse had previously engaged in expropriating funds from Jewish accounts, transferring them instead to Nazi clients. This revelation is particularly chilling, as it underscores the extent to which financial institutions were intertwined with the machinery of genocide.

The inquiry has also unveiled troubling details regarding Credit Suisse’s banking relationships with the SS, which were found to be more extensive than previously acknowledged. The economic arm of the SS maintained an active account, enabling financial transactions that facilitated the Nazi regime’s operations. The Telegraph reported that Barofsky provided further shocking insights, revealing that Credit Suisse had a hand in financing ratlines—covert escape routes utilized by prominent Nazis seeking refuge in Argentina to evade Allied justice. These ratlines, which were instrumental in facilitating the flight of war criminals, were reportedly supported by financial resources from the Swiss bank, allowing them to flourish even in the aftermath of the war.

Moreover, the investigation has illuminated the role of Argentine authorities, who allegedly used accounts at the Swiss bank to orchestrate bribes and payments to European officials, thus ensuring the continued operation of these illicit ratlines. Current estimates suggest that such financial dealings could amount to approximately 17 million Swiss francs, or £16 million, underscoring the staggering scale of complicity among those who were meant to uphold ethical standards in banking.

The inquiry has not been without its challenges. Barofsky has encountered significant obstacles, particularly in the form of over 150 crucial documents that UBS is reportedly withholding from the investigation. As was noted in The Telegraph report, during the Senate hearing, he expressed his concerns, stating, “What we’re talking about are documents that are relevant to the question of whether a Nazi had an account or didn’t have an account at Credit Suisse.” The missing papers, which Barofsky suspects may include lists of German clients, looted art, and other valuables, are deemed essential to the core of the investigation. This withholding of information has drawn sharp criticism from U.S. senators, who have characterized UBS’s conduct as “absurd” and “a historic shame that’ll outlive today’s hearing,” as articulated by Senator Grassley.

Senator John Kennedy from Louisiana took the opportunity to confront UBS’s leadership directly, asserting that the bank’s actions were primarily motivated by a desire to avoid financial repercussions. “That’s what this is all about, you don’t want to pay any more money… If you owe more money, then by God, pay it,” he admonished Robert Karofsky, the head of UBS Americas. The report in The Telegraph observed that such sentiments reflect a broader frustration among lawmakers regarding the perceived reluctance of financial institutions to confront their historical complicity and address the moral imperatives associated with these revelations.

In defense of its actions, UBS executives have categorically denied any allegations of attempting to silence Jewish advocacy groups, including the Simon Wiesenthal Center (SWC). However, they have qualified their willingness to release the withheld documents, stating that they require assurances that the bank will not be subjected to lawsuits as a result. This stance raises further questions about the ethics of financial transparency and the lengths to which institutions will go to protect their interests.

The historical context surrounding the current investigation is essential for understanding the implications of these findings. In 1999, both UBS and Credit Suisse issued apologies and reached a global settlement regarding Nazi-era claims, which included pledges to address any future allegations, as reported in The Telegraph. UBS has framed the current investigation as a voluntary initiative, a claim that stands in stark contrast to the weight of evidence emerging from Barofsky’s findings.

As the investigation unfolds, expectations are high for a comprehensive report that will not only detail the findings but also hold those responsible accountable. Senate judiciary committee aides have indicated that the investigation is projected to conclude by early summer, with a final report anticipated by the end of the year. The implications of this inquiry extend far beyond individual accounts; they challenge the very foundations of financial ethics and the responsibilities of institutions in addressing historical injustices.

The Telegraph of the UK report highlighted the intricate web of financial transactions that facilitated not only the Nazi regime’s operations but also the subsequent evasion of justice. The implications of this inquiry resonate deeply within contemporary society, as they compel us to confront uncomfortable truths about the past and the ongoing responsibility of institutions to rectify historical wrongs.

The investigation into UBS and its predecessor’s role in Nazi-era financial dealings serves as a stark reminder of the enduring impact of history on present-day ethics. As more details emerge, the world watches closely, hoping for a reckoning that not only addresses past injustices but also sets a precedent for accountability in the financial sector. The legacy of the Holocaust demands that we confront these issues with unwavering resolve, ensuring that the lessons of history are not forgotten but rather serve as a guiding principle for future conduct.

In the pursuit of justice, it is imperative that financial institutions recognize their moral obligations and the profound implications of their actions. The recent revelations surrounding UBS are not merely historical footnotes; they are a call to action, urging us to confront the shadows of the past and take meaningful steps toward reconciliation and accountability. The road ahead may be fraught with challenges, but the pursuit of truth must prevail, illuminating the path toward justice for those who suffered unimaginable horrors.