|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Tzirel Rosenblatt

A German appellate court has ruled that the Buchenwald concentration camp memorial is within its rights to prohibit visitors from wearing the Palestinian keffiyeh on its grounds, affirming the site’s prerogative to shield commemoration ceremonies from political displays. The decision, handed down on Wednesday by the Higher Administrative Court of Thuringia, underscores the profound sensitivity surrounding Holocaust memorials in Germany and the competing tensions between free expression and the protection of Jewish security in public spaces.

According to a report on Friday at The Jewish News Syndicate (JNS), the ruling arose from a case brought by a woman who had been denied entry to Buchenwald’s 80th liberation anniversary ceremony in April after arriving wearing the black-and-white patterned scarf. The keffiyeh, long associated with Palestinian nationalism, has in recent years become a polarizing symbol, frequently interpreted by Jewish communities as an emblem of anti-Israel agitation.

The woman, whose name was not disclosed in keeping with German privacy laws, had argued that the refusal infringed on her constitutional right to freedom of expression. She subsequently sought permission from the court to attend a second commemorative ceremony this week while wearing the garment.

Judges rejected her petition, concluding that her stated intent—protesting what she described as the memorial’s “one-sided support” of Israel—would create an unacceptable disturbance in the commemorative setting. In its written opinion, the court was unambiguous: “It is unquestionable that this would endanger the sense of security of many Jews, especially at this site.”

As the JNS report emphasized, the court’s reasoning framed the memorial’s “interest in upholding the purpose of the institution” as paramount. While Germany’s constitution robustly protects freedom of expression, the judges determined that in this case the protection of Holocaust remembrance and the safeguarding of Jewish visitors outweighed the individual’s political statement.

The case follows heightened scrutiny over the memorial’s approach to contemporary political symbolism. As JNS reported, an internal Buchenwald document leaked last month described the keffiyeh as “closely associated with efforts to destroy the state of Israel.” The wording provoked criticism from some activists, who argued that such phrasing stigmatized a cultural garment.

Memorial director Jens-Christian Wagner later attempted to clarify the institution’s stance. While conceding that the language in the leaked document had been “mistaken,” Wagner affirmed that the keffiyeh could be restricted if deployed in a manner that relativizes or diminishes the singularity of Nazi crimes. “The keffiyeh is not banned outright,” he told reporters, “but it can be prohibited in contexts where it undermines the educational mission of the memorial.”

For Wagner and his colleagues, the stakes are particularly high: the integrity of remembrance ceremonies must not be diluted by external conflicts or symbols that risk politicizing the space. As the JNS report observed, memorial sites across Germany increasingly face these dilemmas as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict reverberates into European public life.

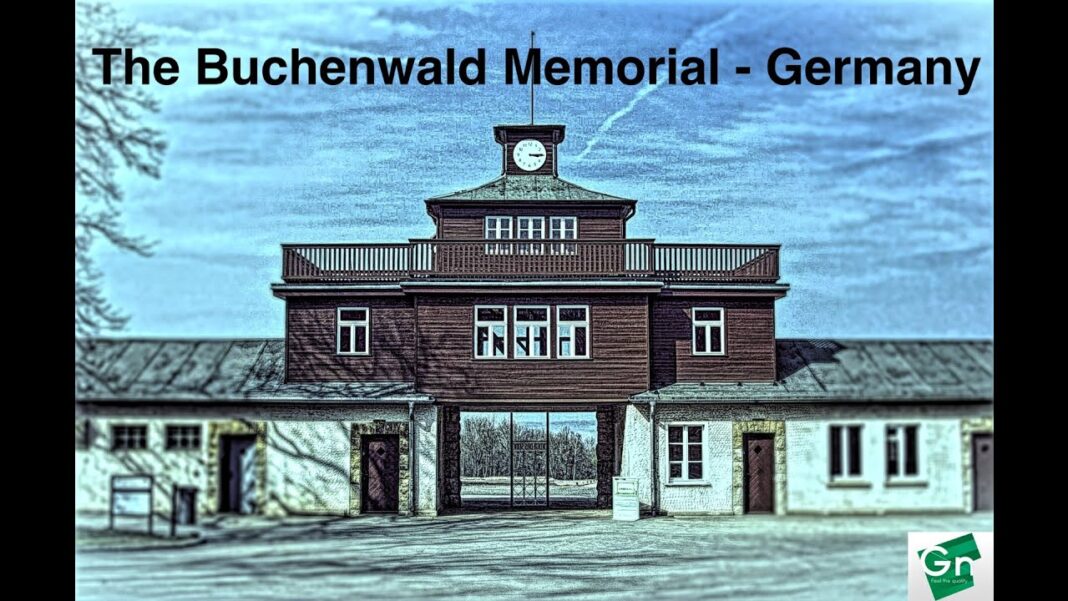

Buchenwald, situated near Weimar in the German state of Thuringia, is among the most infamous Nazi concentration camps. Between 1937 and 1945, approximately 340,000 people were imprisoned there; some 56,000 perished within its confines, succumbing to starvation, disease, medical experiments, or execution.

The camp’s annex, Mittelbau-Dora, claimed an additional 20,000 lives as inmates were conscripted into forced labor to build V-2 rockets. Liberation by U.S. forces in April 1945 revealed the enormity of the atrocities, cementing Buchenwald’s place as a central site of Holocaust memory.

As the JNS report noted, the 80th anniversary ceremony earlier this year drew survivors, descendants, and international dignitaries to honor the dead. The appearance of contemporary political symbols, such as the keffiyeh, was widely perceived as undermining the solemnity of the occasion and risking the re-traumatization of survivors and Jewish attendees.

The ruling in Thuringia carries broader implications for the way Holocaust memorials across Germany may regulate expressions of political solidarity that intersect with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. While critics will likely portray the court’s decision as a curtailment of free expression, Jewish organizations and survivor groups have applauded the outcome, stressing that the dignity of remembrance sites must be preserved against politicization.

As JNS has reported, European Jewish communities have grown increasingly concerned about the intrusion of anti-Israel activism into Holocaust remembrance spaces, fearing that such gestures not only dishonor the dead but also foster an environment of intimidation for the living.

The court’s opinion echoed this sentiment, insisting that the right to personal protest could not eclipse the sanctity of a memorial dedicated to victims of genocide. By affirming the memorial’s authority, the decision effectively reasserts the primacy of remembrance over contemporary political grievances in spaces consecrated to the Holocaust.

The Thuringian court’s decision represents more than a localized dispute over attire at a single ceremony. It is, as the JNS report observed, a landmark affirmation that Holocaust memorials in Germany may lawfully restrict political symbolism to preserve the sanctity of commemoration and protect Jewish visitors.

By ruling that the wearing of the keffiyeh in such a context would “endanger the sense of security of many Jews,” the court emphasized Germany’s enduring responsibility to safeguard Holocaust memory against appropriation or disruption. For survivors, descendants, and Jewish communities, the verdict is likely to be viewed as a necessary defense of dignity.

As debates about free expression and the limits of political symbolism continue to roil European public life, Buchenwald now stands as a test case, one in which the imperative of remembrance was deemed to outweigh the assertion of protest.

What has Israel to do with it? Why repeat her nonsense as though it’s true. She is an anti Semite who hates Jews and wanted to disrupt the memorial services.

How did I know it was a woman before reading it?