|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Fern Sidman – Jewish Voice News

For more than a century, the Cairo Geniza has been regarded as one of the most extraordinary archaeological and cultural treasures in Jewish history—a vast, accidental archive containing the religious, commercial, social, and intellectual remnants of a medieval civilization that once flourished in the Middle East. Yet despite its unmatched significance, the sheer magnitude and complexity of the collection have long confounded scholars. More than 400,000 documents—some whole, many fragmentary, written in multiple languages and scripts—have defied complete cataloguing, transcription, and contextualization.

Now, as Reuters reported on Tuesday, researchers in Israel and Europe are deploying artificial intelligence to fundamentally reshape what is known about the Geniza and unlock what may be the single richest repository of Jewish historical knowledge ever assembled.

Using advanced transcription models trained on ancient handwriting, the MiDRASH project—funded by the European Research Council and anchored to the National Library of Israel’s digital Geniza collection—aims to turn images of fragile, handwritten medieval documents into machine-readable text. Scholars believe this will allow for rapid cross-referencing, reconstruction of long-split fragments, and the emergence of patterns previously invisible to even the most seasoned experts.

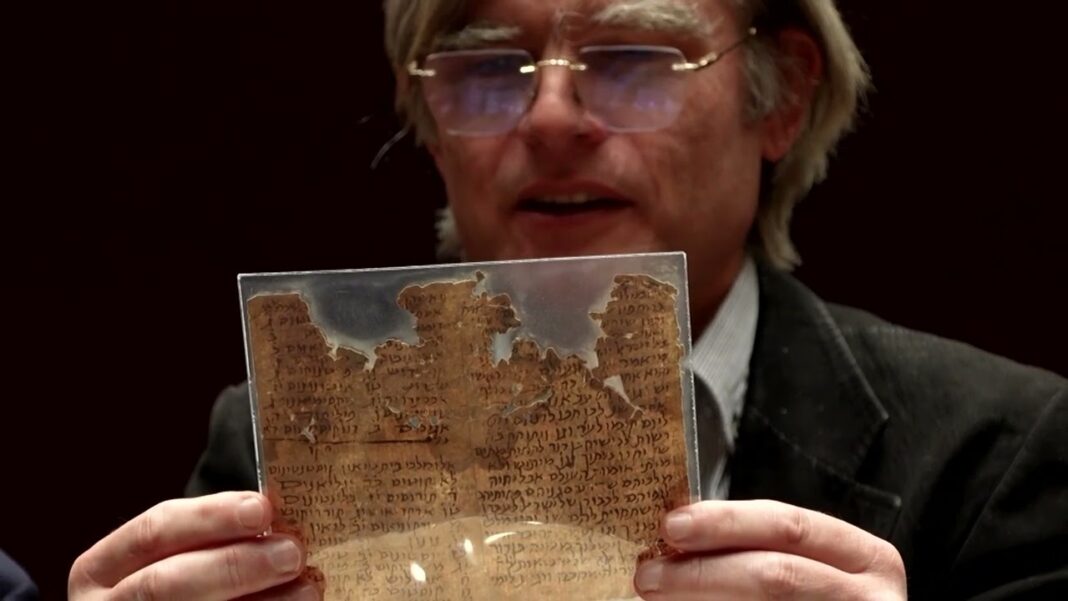

If successful, the effort will not merely accelerate academic research—it promises to recreate the lived experience of a medieval Jewish world whose voices have remained muted by time, language barriers, and the degradation of manuscripts. As one of the project’s lead researchers, Daniel Stokl Ben Ezra of the École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris, told Reuters, “We are constantly trying to improve the abilities of the machine to decipher ancient scripts.” The technological leap forward, he emphasized, could open the entire millennium-spanning archive “to many different researchers” and dramatically widen public access.

The Cairo Geniza, housed for centuries in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fustat—a historic district of Cairo—contains documents dating from roughly the 9th to the 19th centuries. Unlike typical synagogue genizot, where worn-out scrolls or prayer books were placed awaiting ritual burial, this storeroom accumulated everything: legal contracts, marriage agreements, business ledgers, personal letters, philosophical treatises, children’s writing exercises, and scraps of poetry.

Many documents have no immediate religious significance. Instead, they paint a vivid portrait of society in motion: disputes between merchants, bills of sale for textiles, shipping receipts for goods traveling from India or Sicily, rabbinical responsa addressing mundane or metaphysical queries, and delicate exchanges between family members separated by illness, travel, or war.

But the Geniza’s disordered state has long made its riches notoriously difficult to unlock. Although the entire collection has been digitized in recent years, the Reuters report noted that only about ten percent of its contents have been transcribed, and far fewer have been thoroughly studied. Thousands of fragments remain scattered across academic libraries in Cambridge, Oxford, New York, Jerusalem, and Budapest.

Many pieces are tiny, with jagged edges and missing lettering. Some are palimpsests—texts written over older, partially erased writings. Others are written in Hebrew using Arabic grammar (Judeo-Arabic), requiring specialized training to understand. Some are in Aramaic, still others in Yiddish, Ladino, or Greek. Some scripts are ornate, others rushed and nearly illegible. Many belong to longer documents that were torn or decayed centuries ago.

The result is a scholarly puzzle of staggering dimensions—one now potentially solvable through artificial intelligence.

The MiDRASH project (an acronym derived from Machine-Reading and Decipherment of the Cairo Geniza) trains neural networks to recognize handwriting styles from different centuries and geographic regions. By feeding the model thousands of existing transcriptions and high-quality scans, researchers are gradually teaching it to identify letters, ligatures, and word patterns—even in scripts that human scholars sometimes struggle to decipher.

As the Reuters report described, the AI is capable of reading Hebrew square script alongside the flowing cursive of Judeo-Arabic or even the more angular writing of medieval Yiddish. What once required decades of training in paleography might soon be done in minutes.

Transcriptions produced by the system are then reviewed by scholars to verify accuracy. Corrected results are fed back into the algorithm, increasing its resilience and enabling it to decode more challenging samples. The project’s leaders believe that within a few years, the majority of Geniza documents may be searchable through digital text.

The implications are vast. Once transcribed, names, places, commodities, legal formulas, or rabbinic quotations can be instantly searched across hundreds of thousands of documents. Fragments physically dispersed between libraries in London and Jerusalem might be digitally reunited for the first time in a millennium. Patterns in trade flows, migration, marriage customs, or halachic rulings could emerge with unprecedented clarity.

As Stokl Ben Ezra explained to Reuters, “The modern translation possibilities are incredibly advanced now and interlacing all this becomes much more feasible, much more accessible to the normal and not scientific reader.” The democratization of access, he noted, is one of the project’s most profound goals.

One example of the project’s potential impact comes from a recently transcribed document: a 16th-century letter written in Yiddish by a widow named Rachel who lived in Jerusalem. She addressed her son in Cairo, describing personal hardships and the daily struggles of life in Ottoman Palestine. In a poignant twist, the son added his reply in the margins, recounting his own efforts to survive a devastating plague sweeping through Cairo at the time.

Such intimate correspondence offers a window into Jewish life that has rarely survived intact elsewhere. Letters like Rachel’s illuminate emotional lives, family structures, gender roles, and socioeconomic realities that historians could previously access only faintly.

AI-assisted transcription allows these voices—buried for centuries—to speak again.

The Cairo Geniza survived largely because the Ben Ezra Synagogue’s storeroom was unusually dry and relatively undisturbed for nearly a thousand years. As the Reuters report recounted, Cairo in the Middle Ages was the preeminent city of the Islamic world—a hub of global trade and intellectual exchange surpassing Damascus and Baghdad. Its Jewish community thrived, enriched both by local prosperity and by waves of immigrants, including refugees fleeing the Inquisition in Spain.

Among its most famous residents was Moses Maimonides, the towering medieval philosopher and physician to the Ayyubid court of Saladin. Maimonides worshipped at the Ben Ezra Synagogue, and several of his own manuscripts were later found in the Geniza—an unparalleled link to one of Judaism’s greatest minds.

Over centuries, as dynasties rose and fell, the Jewish community dutifully filled the Geniza with religious writings, halachic debates, business calculations, medical prescriptions, astronomical charts, poetry, and countless scraps of daily existence. When scholars “discovered” the Geniza in the late 19th century, they realized the magnitude of what had been preserved: a living tapestry of Jewish civilization spanning continents and centuries.

Yet even after more than a century of scholarly effort, enormous gaps remain. Tens of thousands of fragments represent unknown authors, unrecorded stories, and unstudied communities whose legacies have yet to be decoded.

It is here that AI may have its greatest transformative effect.

Researchers believe that by transcribing and cross-referencing the Geniza’s documents, they could reconstruct detailed social networks—mapping families, business partnerships, political alliances, rabbinic lineages, and migration routes. Stokl Ben Ezra told Reuters that “the possibility to reconstruct, to make a kind of Facebook of the Middle Ages, is just before our eyes.”

Such a database could trace the movement of a merchant’s goods from India to Sicily, follow the correspondence of a rabbi across three continents, or reveal how legal precedents spread from Babylon to North Africa. It might identify individuals whose names appear only as faint mentions across dozens of fragments. It could illuminate women’s economic roles, the spread of medical knowledge, or Jewish-Islamic intellectual exchange in the medieval marketplace of ideas.

This possibility—previously unimaginable—reflects the convergence of digital humanities, artificial intelligence, and an ancient treasure trove of cultural memory.

As the Reuters report highlighted, the project is not only for scholars. AI transcription will allow ordinary readers, teachers, genealogists, and students to explore documents that were once the exclusive domain of specialists. Translation tools will make Judeo-Arabic correspondence readable in English, Hebrew contracts accessible to Spanish readers, and Yiddish letters legible to anyone with curiosity and internet access.

Funded by the European Research Council and supported by institutions across Israel, Europe, and the United States, MiDRASH represents one of the most ambitious digital-humanities projects ever undertaken in Jewish studies.

It is a historic moment—one in which artificial intelligence serves not to erase the past but to recover it.

If successful, the project will allow the Cairo Geniza to speak fully for the first time in its thousand-year existence, illuminating the forgotten lives of merchants and midwives, poets and philosophers, widows and scribes—an entire civilization preserved in fragments and now, finally, reassembled.

And with each line decoded, the medieval world that Jews once inhabited—its rhythms, struggles, joys, and ordinary humanity—will grow clearer, animated not only by the tools of modern technology but by the enduring power of historical memory.

Anyone able to decipher this vague use of the English language: “the enduring power of historical memory.”?