|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

A Global Index of Hardship: What the 2025 “Lowest Quality of Life” Rankings Reveal About a World Under Strain

By: Carl Schwartzbaum

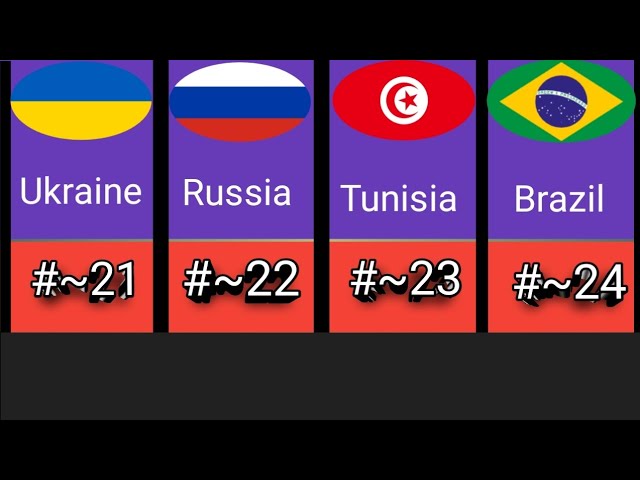

The newly circulated World of Statistics graphic ranking the “Top 25 Countries with the Lowest Quality of Life in 2025” offers more than a stark numerical hierarchy; it provides a compressed portrait of geopolitical instability, economic fragility, and social distress across multiple continents. While any such list is an imperfect snapshot—subject to methodological limitations, data variability, and the dangers of overgeneralization—it nonetheless reflects genuine patterns that policymakers, analysts, and humanitarian organizations would be unwise to ignore.

From Nigeria at the top of the list to Tunisia rounding out the ranking, the compilation reflects a world in which the burdens of conflict, corruption, inflation, climate shocks, and institutional decay increasingly fall on already fragile states. It also underlines a geopolitical truth often overshadowed by daily news cycles: global inequality is widening, and millions live under conditions that policymakers in wealthier capitals only discuss in the abstract.

Africa appears prominently at the top of the list, with Nigeria, Egypt, Kenya, Morocco, and Tunisia all occupying positions in the lower half of global living standards. Nigeria’s ranking as number one is particularly striking—yet unsurprising to long-time observers of West African politics. Despite being one of the continent’s largest economies and a major energy producer, Nigeria grapples with a perfect storm of insurgent violence, widespread kidnapping, collapsing infrastructure, and soaring food inflation. These converging crises have eroded purchasing power, shattered public confidence, and reduced the lived experience of daily life for millions of citizens.

Egypt, similarly, continues to struggle under spiraling debt, a weakening currency, and politically repressive conditions that constrict civil liberties and economic mobility. Its presence among the top ten underscores how even regional powers can be brought low by structural economic distortions and a lack of political reform.

Kenya, Morocco, and Tunisia reflect another category: states that are not collapsing but are stagnating. They confront chronic unemployment, limited economic diversification, and increasing social unrest, conditions that gradually but consistently weigh down quality-of-life indicators.

The list also lays bare the multifaceted crises reshaping Asia. Bangladesh and Sri Lanka—ranked second and fourth—illustrate the fragile underbelly of South Asian development. Bangladesh’s rapid economic growth has been overshadowed by rampant corruption, devastating flooding, migration pressures, and a sharply deteriorating political environment. Sri Lanka, still reeling from its 2022 sovereign debt crisis, continues to endure fuel shortages, food insecurity, and political instability. The social contract remains fractured.

Iran, ranked sixth, faces intense domestic repression, international sanctions, and a youth population disillusioned with clerical rule. Quality of life declines not only because of economic hardship but because of a pervasive sense of civic suffocation.

Pakistan’s placement reflects a similar pattern: rolling blackouts, inflation, political volatility, and the enduring threat of extremist violence continue to drag down national morale and economic prospects.

Even middle-income countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand appear on the list—an indication that economic growth alone does not immunize societies against problems such as environmental stress, widening wealth inequality, and fragile labor protections.

Venezuela’s presence in the top three serves as a tragic reminder of one of the hemisphere’s most dramatic national collapses. Once among Latin America’s wealthiest economies, the country is now defined by hyperinflation, authoritarian governance, and a mass exodus that has reshaped migration flows across the region. Its ranking reflects not only economic misery but political disenfranchisement and humanitarian decay.

Peru, Chile, and Colombia highlight another reality: instability does not require outright collapse. These Andean nations struggle with acute political polarization, social fragmentation, corruption scandals, and persistent inequality. Even relatively stable democracies like Chile have witnessed explosive discontent over living costs, pensions, and the perceived failures of political elites.

Ukraine and Russia appear side by side near the bottom of the list, an unintended but telling reflection of the devastation wrought by prolonged war, militarization, and economic sanctions. Ukraine’s quality of life has been ravaged by mass displacement, destroyed infrastructure, and the emotional toll of unending conflict. Russia’s inclusion, meanwhile, reflects economic contraction, international isolation, demographic decline, and intensifying political repression.

Azerbaijan, though richer than many listed countries, suffers from a different form of deficit: a political environment dominated by one ruling family for decades, limited civil liberties, and regional tensions that have periodically erupted into war.

Lebanon’s ranking at number ten encapsulates a national descent that experts often describe as one of the worst economic collapses in modern history. The country’s currency has lost more than 95% of its value since 2019, public services have withered, sectarian elites continue to block reform, and many families cannot rely on stable electricity or access to health care. For a once-vibrant society, the decline has been both rapid and psychologically punishing.

Beyond individual national crises, the list signals several broader trends shaping global quality of life in 2025:

1. Conflict remains the strongest predictor of societal decline.

Where violence persists—whether insurgency in Nigeria, war in Ukraine, or repression in Iran—quality of life deteriorates rapidly.

2. Economic inequality continues to widen within and between countries.

Even in middle-income states, growth has failed to translate into equitable improvements for the majority of citizens.

3. Climate change acts as a threat multiplier.

Flooding in Bangladesh, drought in Tunisia, and extreme heat in Iran and Pakistan are pushing vulnerable populations closer to the margins.

4. Political dysfunction compounds economic crises.

In Sri Lanka, Peru, Lebanon, and Venezuela, the inability of political systems to adapt has deepened public suffering.

5. Migration patterns are shifting dramatically.

Many of the countries listed are major sources of global migration, reflecting a worldwide vote of no-confidence in local conditions.

A Moment for Reassessment — and Responsibility

The 2025 “Lowest Quality of Life” list should not be viewed as a sensational ranking but as an urgent call for international engagement and national reform. Behind each entry are millions of lives shaped by stagnation, insecurity, and diminishing hope. While global powers often debate high-level geopolitics, the data here underscores a more intimate reality: quality of life is collapsing for some of the world’s most vulnerable populations.

If there is one message embedded in this graphic, it is that global stability cannot be separated from human well-being. Societies with deteriorating quality of life become Petri dishes for extremism, mass migration, authoritarian resurgence, and social rupture. Conversely, investment in governance, institutions, climate resilience, and human development remains the clearest pathway out of the spiral.

With 2025 already marked by geopolitical tension, economic uncertainty, and widening global divides, this ranking is not just a list — it is a warning. Whether nations heed it will shape the decade to come.