|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Jerome Brookshire

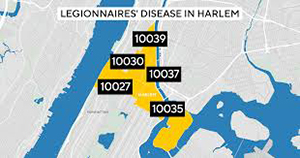

After nearly three weeks of heightened anxiety and public health alerts, New York City officials have declared that the deadly legionnaires’ disease outbreak in central Harlem has come to an end. On Friday, municipal health authorities confirmed that no new cases have been recorded among residents or workers in the affected area since 9 August — a milestone that signals the outbreak has been contained.

According to The Guardian, city data shows that a total of 114 people contracted legionnaires’ disease during the crisis, of whom 90 required hospitalization. Seven residents tragically lost their lives, underscoring both the virulence of the disease and the vulnerabilities within the city’s water infrastructure. Six patients remain under medical care.

In a statement on Friday, Mayor Eric Adams framed the end of the outbreak as both a relief and a call to action. “Today marks three weeks since someone with symptoms was identified, which means New Yorkers should be able to breathe a sigh of relief that residents and visitors to central Harlem are no longer at an increased risk of contracting legionnaires’ disease – but our job here is not done,” Adams said.

As The Guardian reported, the mayor emphasized the need for systemic improvements in public health preparedness. “We must ensure that we learn from this and implement new steps to improve our detection and response to future clusters, because public safety is at the heart of everything we do. This is an unfortunate tragedy for New York City and the people of central Harlem as we mourn the seven people who lost their lives and pray for those who are still being treated.”

The outbreak prompted an immediate investigation by city health officials, who scoured Harlem for potential sources of contamination. Their findings, later confirmed by laboratory testing, traced the legionella bacteria to cooling towers located atop the city-run Harlem Hospital and a nearby construction site.

As The Guardian explained in its coverage, these cooling towers can generate aerosolized water droplets that, if contaminated with legionella, can spread the bacteria widely. Once inhaled, the bacteria can trigger a severe pneumonia-like illness with a potentially fatal course, particularly in vulnerable populations.

Legionnaires’ disease, first identified after a 1976 outbreak at an American Legion convention in Philadelphia, remains a persistent public health risk in urban environments where large-scale water systems are prevalent. The disease is caused by exposure to legionella bacteria, which thrives in warm water conditions, especially in poorly maintained plumbing and cooling systems.

The CDC noted that the primary route of infection is through inhalation of mist or vapor containing the bacteria. A secondary, less common pathway occurs when individuals accidentally aspirate contaminated water into the lungs.

Most healthy individuals exposed to legionella will not become ill. The highest risk groups include people over 50, current or former smokers, and those with chronic health conditions such as diabetes, lung disease, or compromised immune systems.

The symptoms of legionnaires’ disease can take between two and 14 days to appear after exposure. Patients often present with cough, fever, headaches, and muscle aches, as well as respiratory distress. Other manifestations may include gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, diarrhea, and even neurological effects like confusion.

The Guardian underscored the importance of rapid recognition, as early antibiotic treatment is critical to survival. City officials urged anyone with flu-like or pneumonia-like symptoms to seek immediate medical attention.