|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Jeff Gorman

New York City has endured many winters of trial, but few have laid bare the vulnerabilities of a new administration as starkly as the aftermath of Winter Storm Fern. What began as a brutal blizzard followed by a prolonged deep freeze has metastasized into a multifront crisis—one that has not only tested municipal systems but has also strained the political alliances that carried Mayor Zohran Mamdani into City Hall. As The New York Post reported in detail on Monday, the mayor now finds himself under fire not from traditional opponents, but from within his own progressive camp, as left-leaning allies voice alarm over power outages, mounting deaths, impassable streets, and a city seemingly unable to regain its footing.

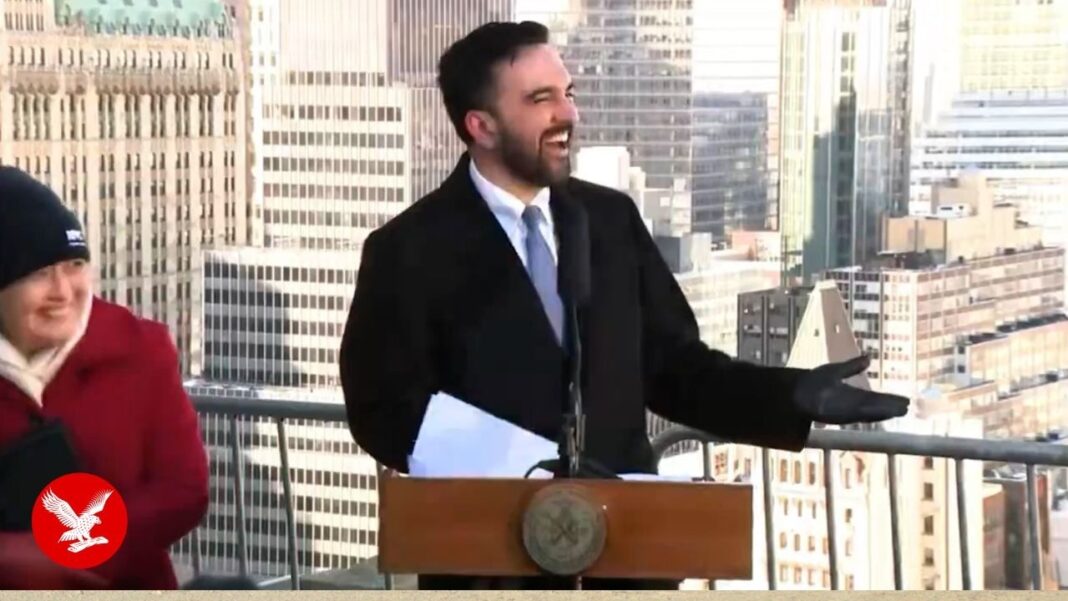

The storm’s human toll has been sobering. In remarks made Monday—delivered incongruously during a press conference announcing free public tours of the David N. Dinkins Municipal Building this June—Mayor Mamdani disclosed that the number of New Yorkers who died during the storm and subsequent cold snap had risen to 16. According to preliminary findings cited in The New York Post report, 13 of those deaths were attributed to hypothermia, while three were linked to overdoses. The deaths occurred between January 24 and Sunday, a grim timeline that underscores how quickly a weather event can cascade into a public health emergency.

Yet even as the mayor sought to project resolve—declaring that “the cold is showing no signs of stopping, so neither will the city’s efforts”—his words rang hollow for many. The confidence of the statement stood in contrast to the persistent disruptions visible across the five boroughs and the intensifying criticism from members of his own Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) circle. As The New York Post report noted, the storm has become the first major stress test of Mamdani’s fledgling administration, and the results have been anything but reassuring.

In Brooklyn’s Park Slope, City Councilwoman Shahana Hanif, herself a DSA member and a political ally of the mayor, took to social media in an uncharacteristically urgent plea. Nearly 2,000 residents were left without power after a Con Edison outage stretched into its second day, depriving households of heat as temperatures plunged. Busy thoroughfares near Barclays Center were left without functioning traffic lights, compounding the sense of disorder. Hanif’s posts begged for “urgent coordination and clear communication” from City Hall and Con Edison alike. “This is becoming unmanageable,” she wrote. “Residents deserve better.”

Hanif was not alone. Fellow DSA Councilman Chi Ossé, also representing Brooklyn, publicly pressed Mamdani to help secure hotel shelter for residents of Bedford-Stuyvesant who had been without power for nearly a week. The tone of these appeals was notable not merely for their urgency but for their public nature—an indication that private channels had either failed or proven insufficient. For an administration that prides itself on solidarity and mutual aid, the spectacle of allies pleading in public marked a significant rupture.

Even outside the DSA ranks, the storm prompted rare dissent from within Mamdani’s broader progressive coalition. Queens Borough President Donovan Richards broke with the mayor over his opposition to dismantling homeless encampments and relocating residents into safer indoor accommodations during the extreme cold. Richards’ criticism, reported by The New York Post, highlighted a fundamental policy disagreement: whether ideological resistance to clearing encampments should yield when life-threatening weather conditions prevail.

Mamdani, for his part, sought to contextualize the deaths by asserting that none of the individuals who died outdoors had been living in homeless encampments at the time. He characterized previous policies of clearing camps as a “failure,” even as he acknowledged that 18 New Yorkers had been involuntarily transported because they were deemed a danger to themselves or others. The city, he said, had made more than 930 placements into shelters and safe havens. Still, critics argued that such figures offered little solace in the face of preventable deaths.

Beyond the tragic loss of life, the city’s physical infrastructure has struggled to recover. EMTs told The New York Post that massive piles of snow left in the wake of the storm have made it perilously difficult to maneuver around hospitals. Stretchers cannot be moved easily, and patients reliant on wheelchairs or walkers have been forced to navigate treacherous terrain. These conditions, emergency responders warned, risk compounding medical emergencies by delaying access to care.

At street level, the most visible symbol of dysfunction has been the accumulation of garbage. With sanitation workers diverted to snow removal and operating on schedules lagging by at least 24 hours, trash and recycling have piled up into towering mounds. The New York Post report documented scenes of refuse rising to astonishing heights, particularly in affluent neighborhoods that had come to expect swift municipal response.

One especially jarring image appeared just blocks from Gracie Mansion, the mayor’s new residence. A garbage pile off East 88th Street, within sight of the mansion and featured prominently on The New York Post’s Monday cover, continued to grow even as the day wore on. Xavier Fernandez, a resident manager at an East End Avenue apartment building, told the paper that sanitation crews had missed three pickups since the storm. Recycling was finally collected Monday, he said, but trash was left behind. “This will be the fourth time we’re putting out garbage on top of this pile and they still haven’t picked it up,” Fernandez said. By his estimate, the heap had reached eight feet tall.

Similar scenes unfolded elsewhere. In the Financial District, workers outside 55 Exchange Place told The New York Post that trash had not been collected since the previous Monday. A sanitation department spokesperson sought to reassure residents, saying that Monday’s trash was finally being collected and that recycling delays of about 24 hours were attributable to the 12 to 15 inches of snow received during the storm. Yet for many New Yorkers, such explanations felt inadequate amid the stench and the rats drawn to the growing mounds.

Power outages compounded the misery. In Park Slope and other Brooklyn neighborhoods, residents endured days without electricity. Con Edison attributed the outages to a mix of road salt and water seeping into underground power systems, exacerbated by compacted snow and ice blocking access to manholes. In some cases, snowed-in cars were parked directly over critical access points. A ConEd spokesperson told The New York Post that crews were working in close coordination with city agencies but that dense, frozen layers of snow and ice had slowed repairs.

For residents like Tatyana Gudin, explanations offered little comfort. Sitting inside an MTA bus converted into an impromptu warming center, Gudin said she had been without power since Saturday night and had resorted to sleeping under three blankets. Her frustration was palpable. “Stop, stop, stop giving excuses, and do better,” she said of the utility company, echoing a sentiment shared by many stranded New Yorkers.

Councilwoman Hanif has since called on Con Edison to reimburse residents for expenses incurred during the outages, including travel and temporary accommodations. City Hall officials said they had been in touch with Hanif and were in direct communication with ConEd since Sunday. Still, the episode has raised broader questions about preparedness, coordination, and leadership during emergencies.

For Mayor Mamdani, the crisis represents more than a logistical challenge; it is a political crucible. His administration’s approach—rooted in progressive ideals and skepticism of traditional enforcement mechanisms—has collided with the unforgiving realities of extreme weather and aging infrastructure. As The New York Post report observed, the mayor’s critics argue that ideology has at times eclipsed pragmatism, leaving the city vulnerable when swift, decisive action was required.

Perhaps most damaging has been the erosion of unity among his allies. The public pleas from fellow DSA members and the open dissent from figures like Donovan Richards suggest that the coalition that propelled Mamdani into office is fraying under pressure. In politics, friendly fire can be more lethal than opposition attacks, and the storm’s aftermath has provided ample ammunition.

Winter Storm Fern will eventually fade from memory, its snowbanks melting and its power lines repaired. But the questions it raised about governance, preparedness, and accountability will linger. New Yorkers, having endured bitter cold, darkened homes, and streets choked with refuse, are unlikely to forget how their leaders responded—or failed to respond—when conditions turned deadly. As The New York Post reported, one truth has become inescapable: the storm did not merely freeze the city; it exposed the fault lines beneath it.