|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Ariella Haviv

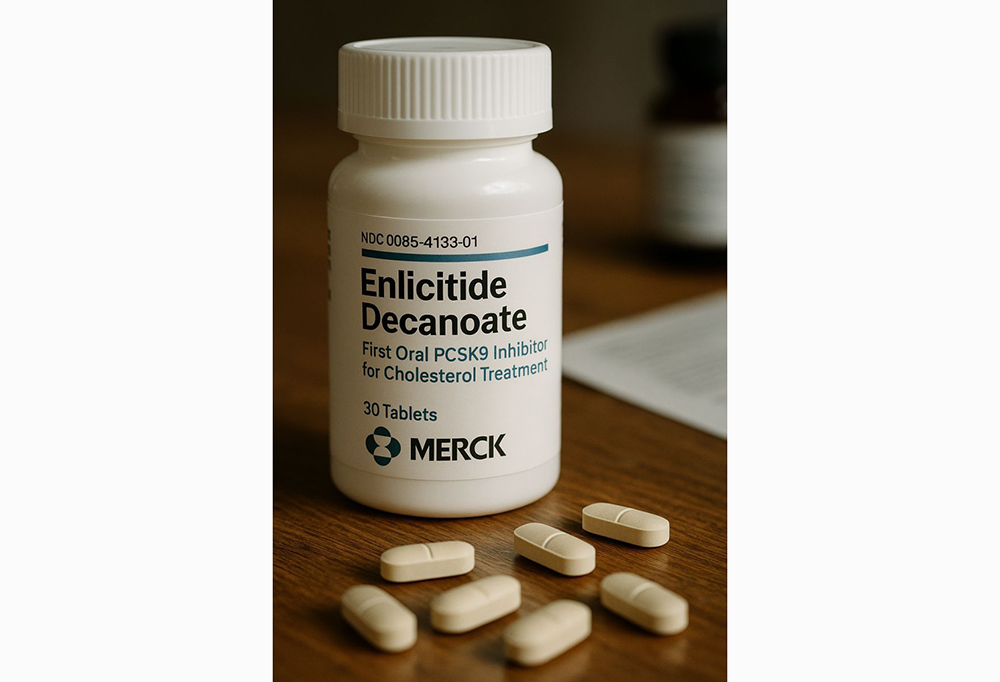

In what The New York Times has called one of the most promising cardiovascular breakthroughs in a generation, Merck & Co. — the pharmaceutical giant that pioneered statins nearly four decades ago — has unveiled a new oral therapy that could redefine how doctors treat high cholesterol. The pill, called enlicitide, has demonstrated unprecedented potency in reducing LDL cholesterol, the so-called “bad” cholesterol that clogs arteries and triggers heart attacks and strokes.

For decades, cardiologists have relied on statins and, more recently, injectable monoclonal antibodies to target LDL. Yet as The New York Times observed in a report published on Saturday, Merck’s new drug offers something that seemed, until recently, almost impossible: a once-daily pill that delivers the same dramatic cholesterol-lowering benefits as costly biweekly injections — at a fraction of the cost and with none of the patient resistance associated with self-injection.

At the annual meeting of the American Heart Association, Merck scientists reported the results of a 24-week clinical trial involving nearly 3,000 high-risk patients who had already suffered a cardiovascular event such as a heart attack or stroke, or who were at substantial risk of one. According to findings cited by The New York Times, those who took enlicitide saw LDL cholesterol levels plunge by as much as 60 percent, matching the efficacy of the powerful injected PCSK9 inhibitors — and without any notable difference in side effects compared with those given a placebo.

For the millions of patients around the world who struggle to control their cholesterol — or who can’t afford the injectable alternatives — enlicitide represents what several cardiologists are calling a “democratizing” moment for cardiovascular medicine.

Enlicitide’s development has been a feat of biochemical ingenuity. The drug works by blocking a liver protein known as PCSK9, which normally interferes with the liver’s ability to clear LDL cholesterol from the bloodstream. By inhibiting this protein, the body can sweep away cholesterol far more efficiently, dramatically reducing the risk of artery-clogging plaque buildup.

The mechanism itself isn’t new: PCSK9 inhibitors like Amgen’s Repatha and Regeneron’s Praluent have been on the market for nearly a decade. But as The New York Times report noted, these therapies are injectable monoclonal antibodies — bulky molecules that must be refrigerated, shipped under strict conditions, and administered every two to four weeks. Their list price exceeds $500 per month, and despite their efficacy, less than one percent of eligible patients use them, largely due to insurance restrictions and aversion to injections.

Merck’s scientists, led by Dr. Dean Li, president of Merck Research Laboratories, set out to create an oral alternative that could perform the same molecular acrobatics inside the body. “The dream is to democratize PCSK9,” Dr. Li told The New York Times. “This dream has the possibility of coming true.”

That dream, however, demanded overcoming formidable scientific hurdles. Traditional small-molecule drugs — the kind that can be taken as pills — were simply too tiny to bind effectively to PCSK9, a protein with a large, flat binding surface that had only been tamed by massive antibody structures in the injectable drugs.

The solution, after a decade of painstaking research, was to design a new class of molecules — small, circular peptides that are a hundredth the size of antibodies but large enough to attach to PCSK9’s critical site. As The New York Times reported, this innovation opens a door not just for cholesterol management but for a whole new generation of orally delivered drugs that could replace injectable biologics in fields ranging from oncology to autoimmune disease.

The trial results, presented Saturday at the American Heart Association’s annual conference, have electrified the medical community. Participants who took enlicitide experienced an average 60 percent reduction in LDL cholesterol within six months — a level that cardiologists once thought unattainable without injections.

There were no significant safety differences between the enlicitide group and those on placebo, an encouraging sign for a therapy likely to be used chronically. According to the information provided in the The New York Times report, Merck will release additional findings Sunday from a smaller study involving patients with familial hypercholesterolemia — a genetic disorder that causes dangerously high cholesterol levels even in young adults.

The implications are profound. “Lower is better for sure,” said Dr. Daniel Soffer, a cardiologist at the University of Pennsylvania, emphasizing that decades of research have shown that every reduction in LDL corresponds to fewer heart attacks and strokes.

Typical LDL levels in untreated adults hover above 100 milligrams per deciliter. Enlicitide, according to the trial data cited in The New York Times report, drove LDL levels in many patients down into the teens — an almost unprecedented physiological achievement. “There appears to be no downside,” Dr. Soffer added, “to having LDL levels this low.”

The New York Times reported that more than six million adults in the United States are eligible for PCSK9-blocking drugs, but most either cannot afford them or are deterred by the complexity of injection regimens and insurance denials.

“An affordable pill, taken daily, that has the same effect as the injected drugs can be a game changer,” said Dr. Christopher Cannon, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He told The New York Times that such a medication could reshape preventive cardiology, particularly if priced comparably to standard oral statins.

Merck’s leadership appears keenly aware of this imperative. Dr. Li has pledged that the company will “keep the price of the PCSK9 pill low so it can be widely used.” Pills are far cheaper to produce and distribute than refrigerated injectables, he noted, adding that he envisions a world where taking a PCSK9 pill is “no different than taking aspirin or a blood pressure tablet.”

Affordability will be central to Merck’s forthcoming application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which The New York Times report said the company plans to submit in early 2026, with a potential market launch by 2027. Before that, however, Merck will complete a massive outcomes trial involving more than 14,500 participants — designed to confirm that enlicitide’s dramatic cholesterol reductions translate into fewer heart attacks, strokes, and cardiovascular deaths.

If successful, enlicitide could mark a turning point in the treatment of heart disease — still the leading cause of death worldwide. According to the American Heart Association, more than 18 million deaths annually are attributable to cardiovascular disease, much of it linked to uncontrolled cholesterol levels.

Statins, introduced in the late 1980s, revolutionized preventive cardiology by reducing LDL levels by 20 to 40 percent. PCSK9 inhibitors pushed those reductions further, but their cumbersome delivery mechanisms kept them from achieving mass adoption. Enlicitide could bridge that divide — merging the convenience of statins with the potency of injectables.

“The lower we can drive LDL safely, the better patients do,” said Dr. David Maron, director of preventive cardiology at Stanford University, in an interview with The New York Times. “If Merck prices this so that people can afford it, it will make a huge difference. This is a really important advance.”

AstraZeneca, another major pharmaceutical player, is reportedly developing its own oral PCSK9 inhibitor, though it remains in earlier clinical phases. Dr. Maron, who serves on an independent safety board for that program, told The New York Times that the entire field could soon see “a fundamental shift” as companies race to convert expensive biologics into accessible oral formulations.

Perhaps the most transformative aspect of enlicitide’s story lies in its scientific architecture. Merck’s success in stabilizing circular peptide structures — molecules previously considered too fragile for oral delivery — may open new frontiers in drug design.

As The New York Times report explained, the peptide-ring method enables the creation of pills capable of targeting previously “undruggable” proteins — those with large, flat surfaces that small molecules could never grip. This could allow oral versions of treatments for conditions ranging from cancer to autoimmune disease to emerge in the coming decade.

“It’s not just about cholesterol,” said Dr. Li. “It’s about creating an entire new class of medicines that can do what biologics do, but in pill form.”

Such advances could reduce global healthcare costs dramatically, given that biologic injectables require specialized manufacturing, refrigeration, and complex logistics. For patients in developing countries, where refrigeration and medical supervision are limited, the impact could be life-saving.

For now, the medical community’s enthusiasm is tempered by cautious optimism. Merck’s 24-week data are compelling, but cardiologists await confirmation from longer-term outcome studies before declaring enlicitide a definitive success. Still, the momentum is unmistakable.

“Lowering LDL has been one of the greatest achievements in modern medicine,” The New York Times wrote in its coverage. “Now, the frontier is accessibility — how to bring these lifesaving benefits to the millions who cannot or will not take injections.”