|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Fern Sidman

The New York Post reported on Monday that newly declassified British intelligence files have shed light on a little-known wartime controversy involving Hans Wilsdorf, the German-born founder of the luxury watch brand Rolex. The records, released by the UK’s National Archives, reveal that MI5 — Britain’s domestic security service — once considered Wilsdorf “most objectionable” and suspected him of harboring strong Nazi sympathies, with possible involvement in espionage during the Second World War.

According to the information provided in The New York Post report, the documents, compiled between 1941 and 1943 and stamped with “Box 500” — the codename for MI5’s wartime headquarters — depict mounting concerns within British intelligence over Wilsdorf’s political loyalties. Despite having been a naturalized British citizen for decades, his Bavarian origins, family connections, and business dealings drew heightened scrutiny in the tense atmosphere of wartime Britain.

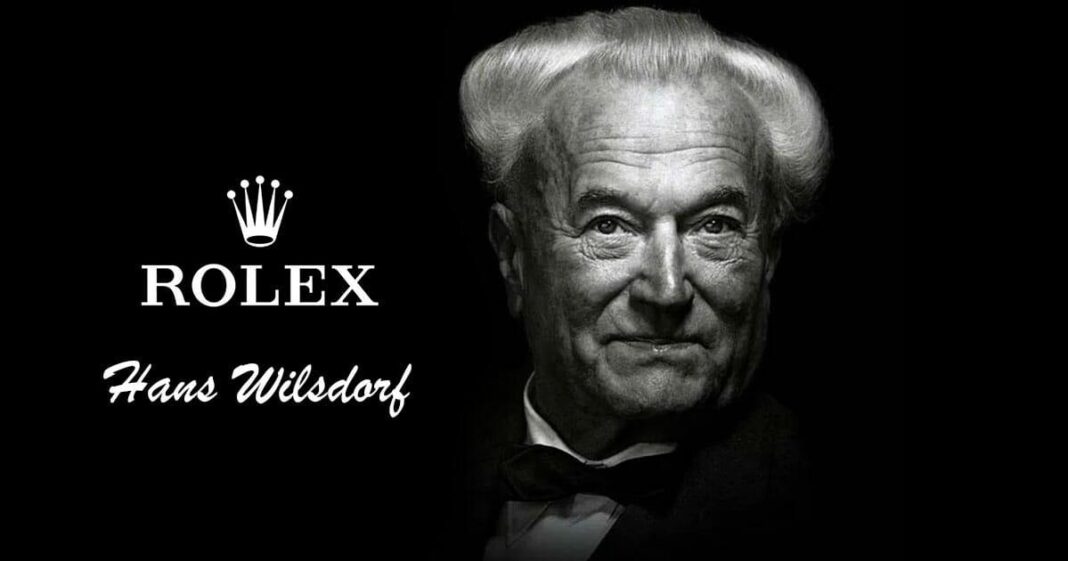

Hans Wilsdorf was born in 1881 in Bavaria and moved to London in 1903, beginning his watchmaking career in Hatton Garden. In 1905, he founded the company that would become Rolex, and in 1919 relocated the firm’s headquarters to Geneva. By then, he was married to a British woman, Florence Crotty, and had established himself as a respected figure in luxury watchmaking.

However, as The New York Post report noted, the early 1940s brought a shift in how British authorities viewed him. A 1941 report from the British consul in Geneva claimed Wilsdorf was “well known for his strong Nazi sympathies” and alleged that his brother, Karl, was working for Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda ministry in Berlin. Swiss federal police were already keeping Wilsdorf under surveillance on suspicion of involvement in spreading pro-Nazi messaging internationally.

The MI5 file contains multiple references to Wilsdorf’s suspected political leanings and outlines a period of close monitoring of Rolex’s operations. By 1943, the agency was observing the company’s British branch in Bexleyheath, concerned that Wilsdorf might be engaged in “espionage on behalf of the enemy.”

The New York Post reported that intelligence officials repeatedly described him as “well known” for his sympathy toward Hitler’s regime. These concerns were compounded by evidence of Rolex’s financial ties to German bankers, which officials feared might give enemy interests influence over the company’s Swiss and British operations.

Tom Bolt, a horology expert who owns a Rolex once sent to a British POW in the German-run Stalag Luft III camp, told The New York Post that the files “show the level of concern within the British authorities about the company’s founder” and that blacklisting him would have been “severely damaging for Rolex.”

One of Wilsdorf’s most celebrated wartime acts — sending free Rolex watches to British prisoners of war — was also scrutinized by MI5. In 1940, Cpl. Clive Nutting, a POW at Stalag Luft III in Poland, wrote to Wilsdorf after German captors had confiscated his watch. Wilsdorf replied, offering a Rolex and telling Nutting not to think of paying until after the war. The company extended this offer to other POWs and also sent food parcels and tobacco.

While this generosity bolstered Rolex’s image, The New York Post report noted that MI5 questioned whether it was a sincere humanitarian gesture or a calculated move to curry favor with the British government. Historian Jose Pereztroika, who discovered the MI5 file and tipped off the Telegraph, suggested the program may have been a strategic “stunt” to win goodwill and secure postwar business advantages, especially since most Swiss watch imports to the UK were banned at the time.

In 1941, the Ministry of Economic Warfare’s Blacklist Section recommended reviewing whether Wilsdorf should be added to Britain’s trade blacklist — a step that could have crippled Rolex’s international sales. While such a move would have delivered a severe commercial blow, officials ultimately advised against it, citing the company’s significant trade with British Empire countries and the lack of direct evidence of hostile actions.

Even so, The New York Post reported that MI5 maintained its view of Wilsdorf as “most objectionable.” By 1943, British officials concluded that although they could not justify blacklisting him without definitive proof, there was “no doubt whatever” about his pro-Nazi political views.

The consul’s reports also cast doubt on the sincerity of his aid to POWs, stating that if earlier intelligence about his sympathies was accurate, his motives “hardly seem likely” to have been purely charitable.

The suspicions were further stoked by Rolex’s involvement in producing dive watches for the Italian navy’s frogmen — an elite maritime unit allied with Nazi Germany. Experts cited by The New York Post say such supply relationships may have fueled MI5’s belief that the company’s leadership was, at minimum, willing to do business with Axis-aligned forces.

Rolex has confirmed awareness of the archival documents and is taking the allegations seriously. A spokesperson told the Telegraph that an independent review is underway, led by Swiss historian Dr. Marc Perrenoud, a specialist in Switzerland’s role during the Second World War.

Dr. Perrenoud is reportedly working with an international committee of historians to examine the claims. “In the interest of transparency, we will publish Dr. Perrenoud’s findings once he has completed his work,” the Rolex spokesperson said.

The New York Post report noted that the company has not commented directly on the specific allegations in the MI5 file, and no evidence has emerged to suggest that Wilsdorf was ever formally charged with espionage or aiding the Nazi regime.

For Rolex, the revelations raise complex questions about the company’s wartime history and its founder’s personal beliefs. While Wilsdorf died in 1960 with a reputation as a visionary watchmaker and philanthropist, the declassified MI5 records reveal that at the height of the Second World War, British intelligence viewed him with deep suspicion.

The documents also provide a rare glimpse into how wartime governments balanced commercial interests against security concerns. As The New York Post report observed, the decision not to blacklist Wilsdorf despite strong suspicions was as much a matter of economic calculation as it was about insufficient proof.

Historians say the case illustrates how business leaders with transnational operations often found themselves navigating — or being accused of navigating — both sides of a global conflict. In Wilsdorf’s case, his German origins, Swiss business base, and worldwide reach made him a natural subject of MI5’s attention.

Despite the depth of the MI5 file, much remains unclear. Were the allegations of strong Nazi sympathies accurate, or were they the product of wartime paranoia? Did Rolex’s gestures toward Allied POWs reflect genuine solidarity, or were they strategically motivated to protect the brand’s postwar market position?

As The New York Post report noted, these questions may hinge on the findings of the ongoing historical review. The results could either confirm lingering suspicions or provide evidence that the accusations were unfounded.

For now, the declassified documents add a shadowed chapter to the otherwise celebrated history of the Rolex brand. They also remind readers that even iconic companies and figures of the 20th century were not immune to the suspicions, political pressures, and moral complexities of wartime.

I don’t understand why this ancient history is a story. We have plenty of active genocidal antisemites now, primarily leftists and Muslims, who pose real threats, and there are numerous genocidal campaigns being waged against the Jewish people. So why is this a story?

A story with true relevance would be to review the history of the New York Times aiding and abetting the Nazis’ war on the Jewish people, and the Reform rabbis who attempted to prevent any assistance to Jews trying to escape the Nazis.