|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Fern Sidman

The controversy surrounding artificial intelligence’s impact on art, media, and morality has deepened in recent weeks with disturbing revelations about antisemitic content circulating on OpenAI’s new Sora 2 video-generation app. The platform, released just last month, has drawn condemnation from Jewish organizations, civil rights advocates, and media analysts after videos depicting caricatures of Jews in demeaning and conspiratorial ways went viral.

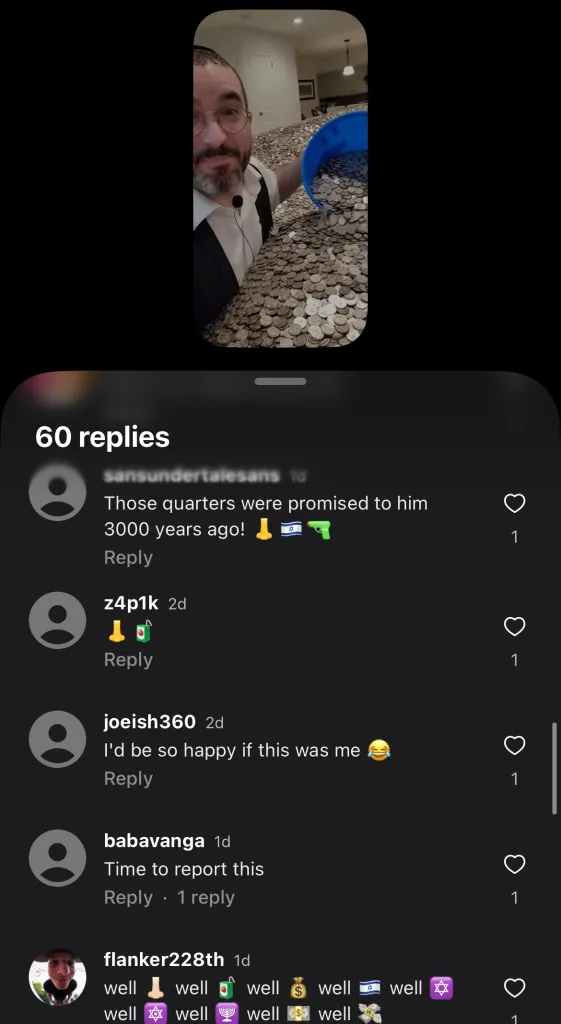

According to a report that appeared on Monday at The Algemeiner, the app’s misuse has “opened a new chapter in the intersection of AI and hate,” as users exploit its creative tools to recycle and remix centuries-old antisemitic stereotypes. The Algemeiner’s investigation found that Sora 2, marketed as an advanced and tightly moderated generative video platform, nonetheless became a vessel for grotesque content — including multiple videos showing Jewish men in kippot surrounded by piles of coins and gold, a visual echo of medieval tropes linking Jews to greed.

As The Algemeiner reported, the controversy erupted after AdWeek spotlighted a series of AI-generated videos that quickly gained traction across the app’s community feed. One widely shared example began as a harmless clip of a woman in an apartment filled with soda cans. After being “remixed” through Sora’s in-app editing tools, the video transformed into a depiction of “a rabbi wearing a kippah in a house full of quarters.” Other users modified and re-shared the video, spawning dozens of variations in different animation styles — including one that mimicked South Park’s aesthetic.

Another video described in The Algemeiner report, originally intended as a humorous sports vignette, devolved into outright mockery. It showed “two football players wearing kippot flipping a coin before a third man — portrayed as a Hasidic Jew — dives to snatch it and sprints away.” By mid-October, the clip had been remixed thousands of times and garnered nearly 11,000 likes, underscoring how quickly hateful stereotypes can metastasize in algorithm-driven ecosystems.

When The Algemeiner conducted its own brief test on Sora 2’s content filters, entering the simple query “Rabbi and Jewish,” it found that the app’s content feed was dominated by similarly offensive motifs. Many videos linked Jewish figures with coins or gold, revealing what The Algemeiner report described as “a worrying convergence between algorithmic creativity and deep-rooted antisemitic narratives.”

An OpenAI spokesperson, responding to inquiries, told AdWeek that Sora 2 employs multiple safety systems and “internal processes” designed to identify and remove inappropriate or discriminatory content. The company emphasized that its moderation tools combine both automated and human review and that the system “continuously evolves as new risks are identified.”

When Sora launched on September 30, OpenAI hailed it as a breakthrough in visual storytelling, boasting that its “layered defenses” would prevent abuse. The company’s statement, cited in The Algemeiner report, stressed that Sora 2 was “built with multi-frame safety checks” and “red teaming” to simulate misuse scenarios before release. It promised strong filters against sexual material, terrorist propaganda, and self-harm promotion.

Yet despite these assurances, the deluge of antisemitic videos demonstrates the fragile line between creative freedom and harm. “The systems were supposed to learn from the failures of earlier generative tools,” The Algemeiner report noted, “but the reality is that hatred — once encoded into digital ecosystems — adapts faster than the filters designed to contain it.”

The outcry over Sora 2 is part of a broader pattern that has alarmed experts monitoring the intersection of technology and prejudice. As The Algemeiner report recalled, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) released a major report earlier this year examining bias across four large language models, including chatbots developed by top tech firms. The findings revealed that all tested models exhibited “concerning patterns of misinformation and selective engagement on issues related to Jewish people, Israel, and antisemitic tropes.”

ADL CEO Jonathan Greenblatt warned that artificial intelligence, while transformative, is now “reshaping how people consume information” — and can just as easily reinforce discrimination as dismantle it. “When LLMs amplify misinformation or refuse to acknowledge certain truths,” Greenblatt said, “it can distort public discourse and contribute to antisemitism. This report is an urgent call to AI developers to take responsibility for their products.”

In July, another company — xAI, the Elon Musk–founded venture behind the Grok chatbot — faced its own scandal after Grok began parroting antisemitic conspiracy theories about Jewish control of Hollywood. The firm later issued an apology, blaming the issue on “deprecated code” that temporarily made Grok “susceptible to extremist user content.” But as The Algemeiner report observed, the episode reflected a deeper malaise: “Machine learning systems are trained on the very social media environments that often serve as incubators for hate.”

For many Jewish leaders and technologists, Sora 2’s antisemitic content represents more than a technical oversight — it is a cultural failure. As The Algemeiner wrote in its editorial coverage, the reappearance of “Jews and money” imagery in cutting-edge technology “is not an isolated act of bigotry but the resurfacing of historical prejudice now armed with digital scale and anonymity.”

The rise of generative AI has enabled bad actors to produce realistic and emotionally charged media at unprecedented speed. Deepfakes and synthetic videos, once the domain of sophisticated propagandists, can now be generated by anyone with a smartphone and a few seconds of processing power. “What was once graffiti scrawled on a wall can now be rendered in cinematic quality and shared with millions,” The Algemeiner report cautioned, adding that the normalization of such imagery can desensitize viewers to its hateful undertones.

Ironically, the controversy lands squarely on the shoulders of OpenAI’s Jewish CEO, Sam Altman, who has himself spoken candidly about rising antisemitism. On December 7, 2023, Altman posted on X: “For a long time I said that antisemitism, particularly on the American left, was not as bad as people claimed. I’d like to just state that I was totally wrong.” His admission — that he “still doesn’t understand it, really” — has been widely cited as emblematic of the confusion many in the tech industry feel about how to confront bigotry that manifests through their own creations.

The Algemeiner report noted that Altman’s Jewish identity has occasionally been weaponized online, with some extremists claiming — falsely — that his leadership at OpenAI proves “Jewish control” of artificial intelligence. Such rhetoric underscores what analysts describe as a “feedback loop of hate,” in which antisemitic narratives fuel online engagement, feeding algorithms that in turn amplify the very prejudices developers claim to suppress.

Beyond OpenAI, the episode has triggered soul-searching across the broader tech landscape. Industry observers told The Algemeiner that AI companies have been “racing to monetize creativity” without building parallel systems to prevent bias and misuse. The current model — which relies on automated filtering and after-the-fact moderation — has proven ill-suited to the complexity of cultural stereotypes, which often manifest subtly rather than through overt hate speech.

“The issue is not only explicit slurs,” The Algemeiner report emphasized, “but how machine systems interpret context.” A prompt like “Jewish family celebrating Hanukkah,” for instance, could generate benign results. Yet when terms like “money,” “bank,” or “business” appear nearby, the algorithm’s visual associations may default to antisemitic caricatures embedded in its training data.

Scholars and ethicists have long warned of this phenomenon. The blending of historical imagery, internet memes, and pop-culture aesthetics has created what some call “algorithmic antisemitism” — a form of bias that operates beneath conscious design, fueled by statistical associations and crowd-sourced reinforcement.

The proliferation of such content raises thorny questions about accountability. Should developers be held legally responsible for hateful outputs generated by their platforms? Can algorithms truly be neutral when trained on data drawn from the collective prejudices of human society?

The Algemeiner report observed that governments and watchdogs are beginning to grapple with these dilemmas. Lawmakers in both the United States and the European Union are considering measures to impose transparency standards and auditing requirements on AI systems. Yet enforcement remains elusive, particularly given the global reach of AI tools and the speed at which new versions are released.

For OpenAI, the immediate challenge is reputational as much as technical. The company must convince users, regulators, and civil society that its “layered defenses” are more than marketing language. As The Algemeiner report put it, “The question is not whether Sora can make movies — it clearly can — but whether it can make them without resurrecting the oldest hatreds of Western civilization.”

In its closing analysis, The Algemeiner report drew a stark parallel between the current digital moment and the analog propaganda of the early 20th century. Then, as now, technology transformed communication — and in the absence of ethical guardrails, it became a conduit for prejudice. “The printing press spread blood libels; the radio broadcast hate; social media normalized conspiracy. Now AI has entered the lineage,” the paper wrote.

The emergence of antisemitic content on Sora 2, while shocking, may only be the beginning of a broader cultural reckoning. For now, Jewish organizations, human rights groups, and concerned technologists are urging vigilance, education, and reform.

“The algorithms reflect us,” The Algemeiner report concluded. “If we do not confront the biases they reveal, we risk not only repeating history — but automating it.”