Written by Rafael Medoff, Yeshiva University Press, 2021, 502 pp. (Distributed by www.Ktav.com)

Reviewed by: Ariella Haviv

It has been said that the true test of a person’s character is how they behave when nobody is looking. I thought of that saying when I reached the point in The Rabbi of Buchenwald when Rabbi Herschel Schacter arrived home from shul one Rosh Hashana evening, accompanied by a grand-nephew, to find a wheelchair-bound woman in considerable distress in the lobby of the apartment building. A power outage had knocked out both the elevator and air conditioning on that extremely warm evening. Without a moment’s hesitation, Schacter—then in his 70s—informed his grand-nephew that they were going to carry the woman, in her wheelchair, up the four flights of stairs to her apartment. And so they did.

We know the leaders of our various Jewish and Zionist organizations from the media coverage that they so actively pursue. We read the statements they make on various issues and we watch them being interviewed. But we know very little about what kind of people they are when the television cameras are turned off. Thanks to Dr. Rafael Medoff’s fascinating new book, The Rabbi of Buchenwald, we now know a lot more about Rabbi Herschel Schacter as a person, in addition to his public persona. And we are the better off for knowing it.

To be sure, this is largely a story of the public life of a Jewish leader. It could not have been otherwise, because Schacter chose to live his life in full public view. A precocious child of interwar Brownsville, Schacter was delivering divrei Torah at local weddings at the age of nine, perched atop a crate or stool. One might say he was destined to become a rabbi. But as it would turn out, that was just the beginning.

Dr. Medoff’s narrative, scholarly yet fast-flowing, chronicles how Herschel Schacter in effect stumbled into history. A newly-minted rabbi at his first congregation (in Connecticut), Schacter was exempt from military service in World War II, but insisted on signing up anyway, as a chaplain. Assigned to the Caribbean, he could have spent the war in comfort and safety, but he insisted on being sent to the front lines in battle-torn Europe.

In April 1945, Schacter’s unit happened upon the notorious Nazi concentration camp of Buchenwald, from which the guards had recently fled. Schacter and his comrades knew vaguely of the Nazi persecution, but President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s War Department saw no reason to apprise soldiers on the ground of what they were going to encounter.

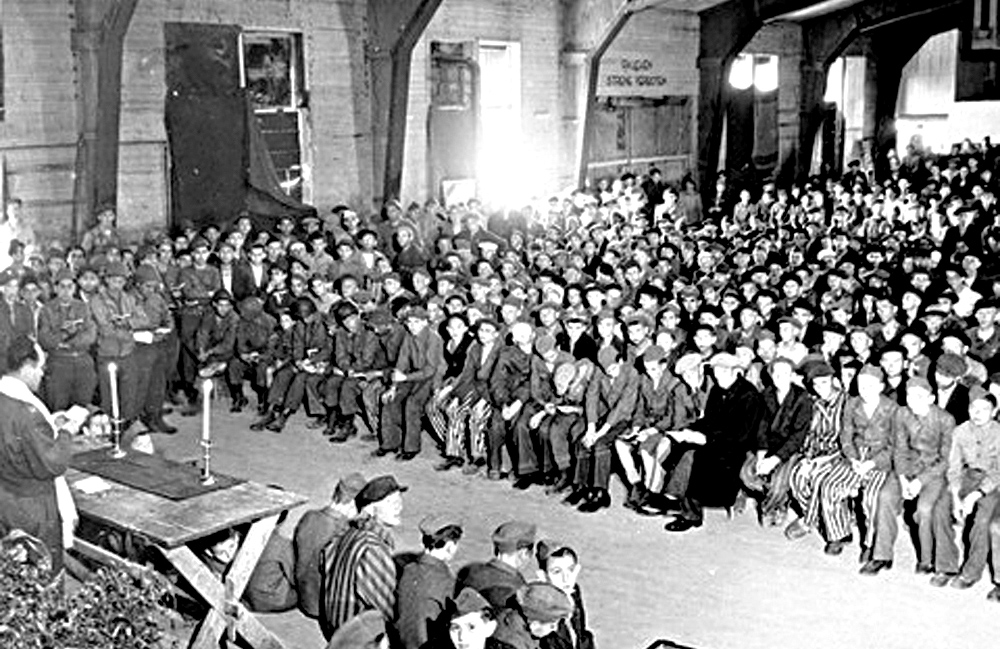

Once again, Schacter could have taken the easy way out. He could have stayed in his barracks in nearby Weimar, doing his job, that is, looking after the religious needs of American Jewish soldiers. Instead, he wrangled permission to stay in Buchenwald, ultimately for two and a half months, in order to devote himself to restoring the shattered lives of the survivors.

Here, in the chapter on Buchenwald, the reader will find story after story which, if Dr. Medoff had not so carefully documented them, one might suspect were apocryphal. Rabbi Schacter smuggled out the survivors’ mail, disguised as own, since civilians were not allowed to use the army’s postal system. He forged identity cards that enabled teenage survivors to be admitted to Switzerland, in defiance of Swiss bureaucrats who sought to enforce a harsh age limit that would have torn families apart. He persuaded his commanding officer to give a tract of land to a group of young survivors to create “Kibbutz Buchenwald,” so they could prepare for life in Eretz Yisrael. Above all, he was truly the rabbi of Buchenwald, comforting and counseling and leading religious services in the very place where torture and murder had so recently reigned.

When the war ends, Medoff’s story is just beginning. We follow Schacter through an almost dizzying series of increasingly important positions in the American Jewish leadership. He rose, first, in the Orthodox community, holding senior posts in the Rabbinical Council of America and the Religious Zionists of America. Eventually he broke through into the secular Jewish hierarchy, as an early leader in the Soviet Jewry protest movement and then as the first Orthodox Jew to chair the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations.

In Dr. Medoff’s view, the reason it took so long—fifteen years—until the Presidents Conference accepted an Orthodox rabbi as its leader was not necessarily because of anti-Orthodox prejudice, but rather a kind of old-fashioned view in the Jewish establishment that Orthodox Jews were uncultured and unsuitable for general communal leadership. Herschel Schacter shattered that glass ceiling.

He was the first Hebrew speaker in that position, as well. Israeli reporters attending Schacter’s installation at the Presidents Conference were startled to find the new leader of organized American Jewry speaking Hebrew like a sabra. His son, Rabbi J.J. Schacter, is quoted as recalling how, while sitting in a Jerusalem cafe one afternoon in 1968, he suddenly heard his father being interviewed—in Hebrew—on Israel Radio. “That’s my Abba!” he proudly announced to the other diners.

It might seem like a small point, but Schacter’s fluency in Hebrew brings to mind a sharp contrast with another Jewish leader about whom Dr. Medoff has written a great deal, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise. Medoff has described, elsewhere, how Benzion Netanyahu (father of Israel’s prime minister) arrived in the U.S. in 1940 as a Revisionist Zionist emissary and promptly sought out Rabbi Wise in order to discuss with him the current state of Jewish affairs. Netanyahu naively assumed that Wise, as the leader of the Zionist Organization of America, could converse with him in Hebrew; he was deeply disappointed to discover otherwise. How sad that many of those who presume to speak for Zionism cannot even speak its language.

In his Jewish policymaking positions, Rabbi Schacter tended to position himself as a man in the middle. Sometimes this worked well, as in the case of his ability to maintain friendly relations with both those to his right—Haredi Orthodox leaders—and those to his left—Reform and Conservative rabbis. In 1955, for example, Schacter’s friendship with the Satmar Rebbe enabled him to negotiate a peaceful resolution to a tense conflict over the opening of a secular youth club adjacent to the Jerusalem haredi neighborhood of Meah Shearim. And in 1968, Schacter convinced Reform and Conservative leaders to join him in protesting the unrestricted conducting of autopsies in Israel, a protest which led Prime Minister Levi Eshkol to change national policy on the issue.

Sometimes, of course, staying in the middle can mean getting knocked by both sides. In his Soviet Jewry activities, Schacter sometimes leaned toward more activist approaches, while at other times he preferred a more cautious policy. As a result, he often found himself at odds with old friends and colleagues who found his positions disappointing.

One of the more intriguing episodes in this vein which is described in The Rabbi of Buchenwald concerns a Soviet Jewry rally at which Schacter found himself “mercilessly heckled” by members of the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry, a group with which Schacter had been involved in its early years. The lead heckler, 17 year-old Yossi Klein (today the award winning author known as Yossi Klein Halevi) was shocked when Schacter calmly invited him on stage and handed him the microphone. Their differences of opinion were not resolved that day, but the civility that Schacter displayed is something that we could use more of in our own tense times.

Schacter’s little-known role in reshaping traditional Jewish voting patterns will surprise and enlighten readers. Like the overwhelming majority of American Jews, Schacter was a lifelong Democrat, but the racial and social turmoil of the late 1960s caused him to reconsider. The nomination of Senator George McGovern—an extreme liberal by that era’s standards—as the Democratic presidential candidate in 1972 troubled Schacter and many other Jews. The breakdown of traditional family values, the undermining of the authority of the police, and the calls for racial quotas (any of this sound familiar?) convinced Rabbi Schacter to lead a movement by Jewish Democrats in support of re-electing President Richard Nixon.

In the end, 35% of Jewish voters backed Nixon—nearly a tripling of what Republican presidential candidates had received not long before. Dr. Medoff suggests that this shattering of the traditional taboo of Jews voting for Republicans could have a significant impact in future presidential elections that are close in key states such as Pennsylvania and Florida.

The Rabbi of Buchenwald does not shy away from acknowledging Schacter’s shortcomings. But above all, it is an earnest and absorbing look at a range of Jewish policy controversies, through the life of a rabbi who played a central role in them.