|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Fern Sidman

The Palace of Versailles, one of France’s most iconic cultural institutions, has launched a renewed provenance investigation into a prized sketchbook by the celebrated Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David, following revelations that the notebook was looted by the Nazis during World War II. According to a report that appeared on Thursday in The Algemeiner, the discovery has prompted profound questions about the stewardship of national collections, the adequacy of France’s restitution efforts, and the unhealed wound that Nazi-era cultural theft continues to inflict on families across Europe.

The investigation began after Radio France was contacted by a descendant of the sketchbook’s original owner, who claimed the work had been seized during the German occupation. Within weeks, the broadcaster unearthed extensive evidence—drawn from public archives, diplomatic files, and the French Holocaust Memorial’s comprehensive database of Nazi-looted art—corroborating the descendant’s account. As The Algemeiner report emphasized, the speed with which this evidence surfaced stands in stark contrast to the decades of inaction by cultural authorities.

The Ministry of Culture acknowledged to Radio France that neither the ministry nor the Palace of Versailles had previously realized the sketchbook’s illicit wartime history. They pledged to “continue research on this notebook and have discussions with the descendants of the owners,” a statement carefully calibrated but nonetheless indicative of a growing recognition that the state must address gaps in its own provenance research.

The revelation that the sketchbook was Nazi loot was particularly jarring to the family of the original owner, Professor Lereboullet. As The Algemeiner report recounted, a relative expressed shock upon learning—by what he described as “total chance”—that the long-missing sketchbook was prominently held in the Versailles collection.

He criticized the disparity in resources France devotes to recovering stolen jewels from museums versus those allocated to returning Nazi-looted art to rightful heirs. “At the moment, there are 100 police officers looking for jewels stolen from the Louvre while to return the works stolen – and there are many at the Louvre and other museums – I find that the means are very, very low,” he said, a sentiment that has gained growing resonance among restitution advocates and Holocaust scholars.

As The Algemeiner report noted, the sketchbook case illustrates the lingering institutional hesitancy that has long plagued France’s post-war restitution efforts. Although the country has made notable progress in acknowledging the breadth of Nazi-era art plunder, its museums remain filled with thousands of objects whose provenance remains incomplete or contested.

Radio France’s findings demonstrate how much of this work remains undone—and how often it has been descendants, rather than state authorities, who have initiated the search for justice.

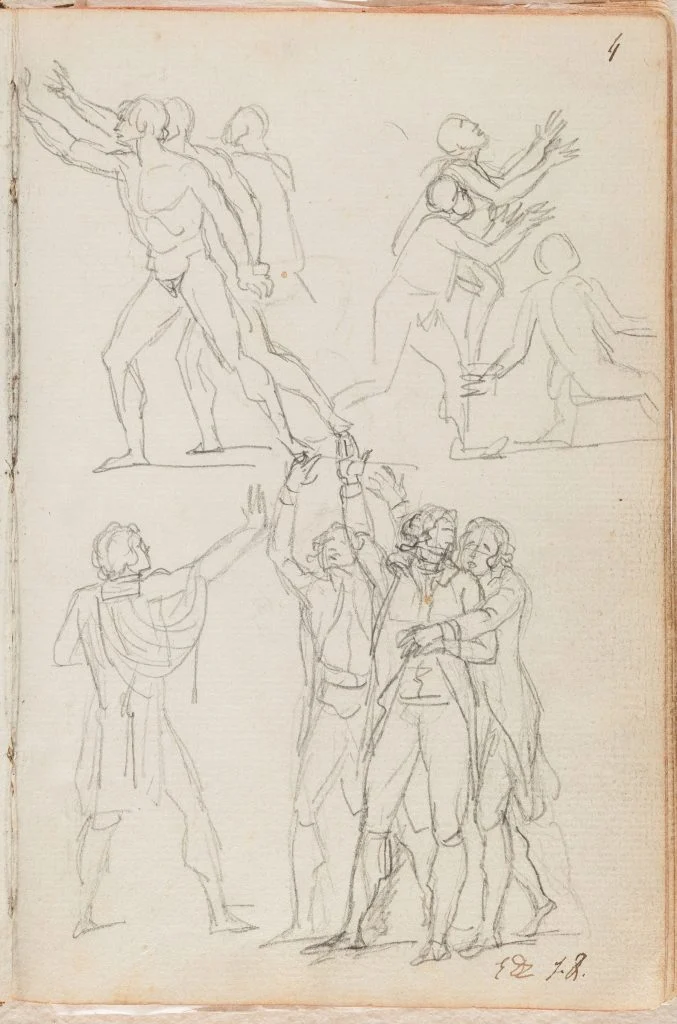

The sketchbook in question dates to 1790 and contains Jacob-Louis David’s drawings, preparatory studies, and annotations for “The Tennis Court Oath,” an ambitious and politically charged painting from the earliest days of the French Revolution. The massive painting—never completed but central to David’s legacy—depicts the dramatic moment on June 20, 1789, when members of France’s Third Estate swore not to disband until the establishment of a national constitution.

As The Algemeiner report detailed, the sketchbook is considered a key document in understanding David’s revolutionary vision. Its artistic and historical significance makes its troubled provenance all the more consequential.

The notebook was part of a private library belonging to Professor Lereboullet, a respected French academic. In July 1940, soon after German forces occupied his home, Nazi troops seized the entire library, including the David sketchbook, as part of a widespread confiscatory campaign targeting Jewish families, intellectuals, and cultural patrons across France.

In November 1945, Lereboullet’s daughter Odile reported the theft to the Commission for Art Recovery (CRA), the French governmental body responsible for identifying and returning looted cultural property. As The Algemeiner report underscored, Odile never received a response.

The silence from the commission, though shocking in retrospect, typifies the post-war era. France received tens of thousands of claims after the liberation, and many—particularly those concerning books, drawings, and works not then considered “museum-grade”—were lost in bureaucratic purgatory.

The sketchbook resurfaced in January 1943, when it was sold at auction by the Karl & Faber art gallery in Munich, a venue known to have trafficked extensively in cultural objects appropriated by the Nazi regime. Its buyer was Otto Wertheimer, a distinguished German Jewish art historian and former Berlin museum curator who fled Nazi persecution and settled in Paris in 1944.

Wertheimer’s involvement complicates the story in a way that The Algemeiner reported with nuance and precision. Wertheimer himself was a victim of Nazi policies, yet his career as a dealer—during and after the war—placed him in the morally ambiguous position of handling artworks with provenance clouded by the political upheavals of the time.

After the liberation, Wertheimer earned renown for acquiring and supplying European masterpieces to institutions across France. In 1951, he sold the David sketchbook to the Palace of Versailles, which made the purchase without—so the ministry now asserts—any awareness of its illicit trajectory.

The transaction was emblematic of a broader problem highlighted in The Algemeiner report: post-war French museums often acquired works from reputable dealers without robust provenance research, operating under the assumption that the chaos of occupation had rendered wartime ownership impossible to trace. Yet, as the Lereboullet family’s experience shows, many of those answers were available—and the state simply failed to pursue them.

Today, Versailles finds itself at the center of a growing public reckoning. The Ministry of Culture confirmed to Radio France that the museum employs a small team of three specialists tasked with verifying the provenance of objects in its vast holdings. Yet that team “had not yet examined this notebook,” a fact that has fueled criticism from historians and restitution advocates.

As The Algemeiner report observed, Versailles has returned just one Nazi-looted item in its history: a Louis XVI-era writing table restituted in 1999.

Given the size of the palace’s collection and its role as a custodian of French national heritage, this limited record has raised uncomfortable questions about the rigor of its research and its commitment to restitution—or lack thereof.

The Ministry’s statement that further investigations will now be undertaken is a step forward, but many observers argue it is not enough. The Lereboullet descendant who initiated the inquiry emphasized his astonishment that so little had been done to clarify the sketchbook’s origins despite its prominence in Versailles promotional materials.

“It’s a key work by David, and the Palace of Versailles does a lot of publicity around these notebooks,” he remarked to Radio France. “So, I’m very surprised that there isn’t more research into their provenance.”

His frustration echoes broader concerns expressed in The Algemeiner report: that France, despite its public commitments to Holocaust memory, has not adequately confronted the enduring legacy of cultural and artistic theft carried out under Nazi rule.

The case of the David sketchbook carries significance far beyond the fate of a single artifact. As The Algemeiner has consistently documented in its coverage of art restitution across Europe and North America, Nazi cultural plunder was not merely incidental but systematic. It targeted the cultural lifeblood of Jewish families, intellectuals, museums, and institutions, stripping them not only of material wealth but of memory, identity, and generational continuity.

France, whose Vichy government collaborated with Nazi occupiers in the confiscation of Jewish property, has faced profound moral questions about its accountability. Efforts to catalogue and return stolen works have expanded in recent years, yet critics argue that the state has still been too reliant on individuals and families to uncover evidence that the government itself should be proactively seeking.

The fact that Radio France’s investigation relied on publicly accessible databases, including the French Holocaust Memorial’s records of looted artworks, underscores this point. The information was available; the authorities simply had not looked.

For Versailles, the sketchbook represents an institutional crossroads. Will the palace commit to a more transparent and ambitious provenance research strategy, or will it continue to rely on minimal staffing and slow-moving procedures that place undue burdens on descendants of Holocaust victims?

As The Algemeiner reported, the palace’s pledge to “continue research” and speak with the heirs is an important gesture. But restitution experts caution that such statements must be matched by resources, accountability, and urgency.

For the Lereboullet family, the investigation is deeply personal. For France, it is emblematic of a broader imperative: to confront a painful past with honesty and to ensure that cultural institutions do not inadvertently perpetuate the injustices of one of history’s darkest eras.