|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

“Jews in the world community from all side needs to find common ground,” said director Oren Rudavsky. “I think he would have sought to unify people, even if we believe different things.”

By: Alan Zeitlin

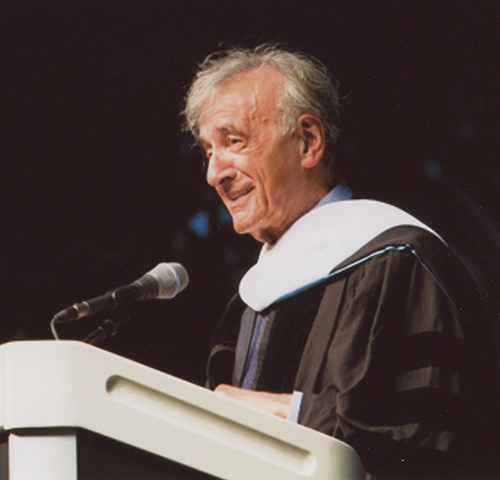

Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel won the Nobel Peace Prize, was given a Congressional Medal of Honor, along with a slew of other awards, and his book Night has sold millions of copies that have been read and discussed by students across the globe.

Wiesel, who died in 2016 at the age of 87, will go down as one of the most famous Jews of all time, who encouraged other survivors to find their voice and speak out. He represented a community that had to grapple with survivor’s guilt for the rest of their lives and went on to become the face of the post-Holocaust generation of global activists.

A new documentary titled “Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire” (Wiesel wrote a book on Chassidic tales and Eastern European Jewry with the same name, published in 1982) chronicles his journey from a boy in Sighet, Romania, where he talks of a small but idyllic life among his town’s Jewish population.

In March 1944, toward the end of World War II, transports of Jews began, and soon, he and his family—he had two older sisters and a younger one—boarded a train to the carnage that was Auschwitz, where he described, early on in the film, seeing live babies thrown into burning ditches. He survived the camp and the Death March to Buchenwald in January 1945, where he was liberated three months later.

“Auschwitz became a center of Jewish history,” said Wiesel in the film. “Everything died in Auschwitz.”

He eventually resettled in France, where he was reunited with his older sisters, Beatrice and Hilda, who survived as forced laborers, at a French orphanage. He worked as a journalist in Paris before leaving for the United States in 1955, where he eventually stayed.

Night, a powerful read that numbers a little more than 100 pages, was originally published in Yiddish in 1956, French in 1958 and English in 1960. It has since been translated into about 30 languages. (In the film, viewers learn that the original “Night” in Yiddish was more than 800 pages and struck an angrier tone.)

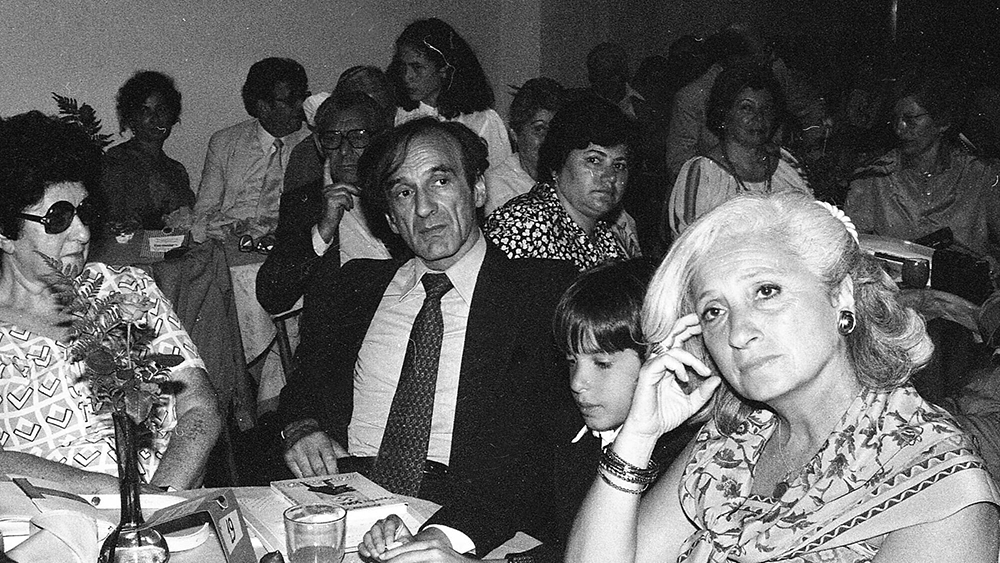

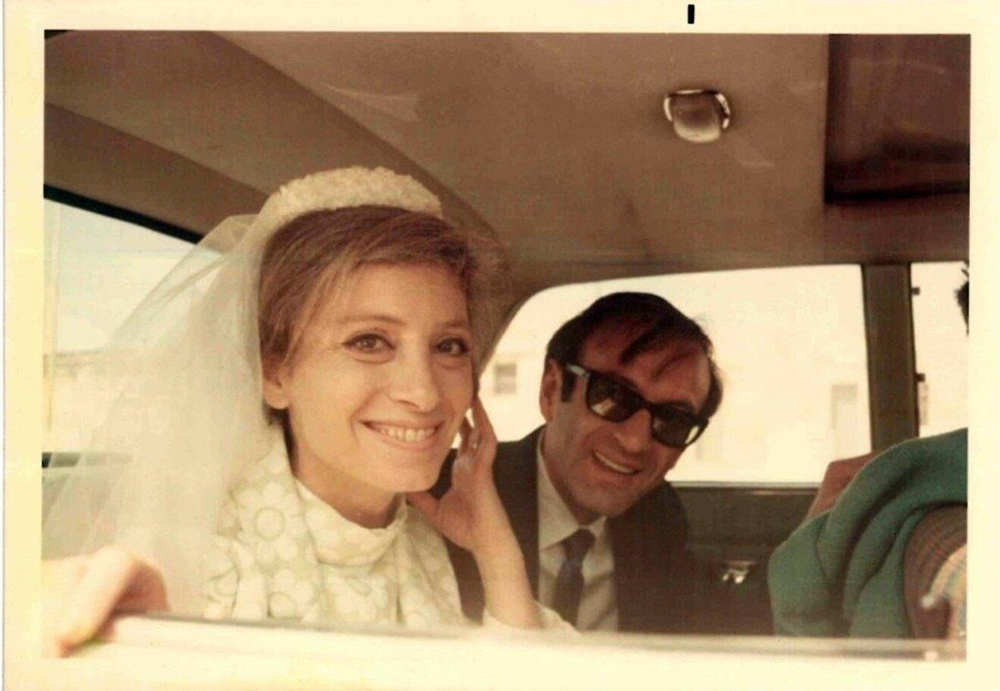

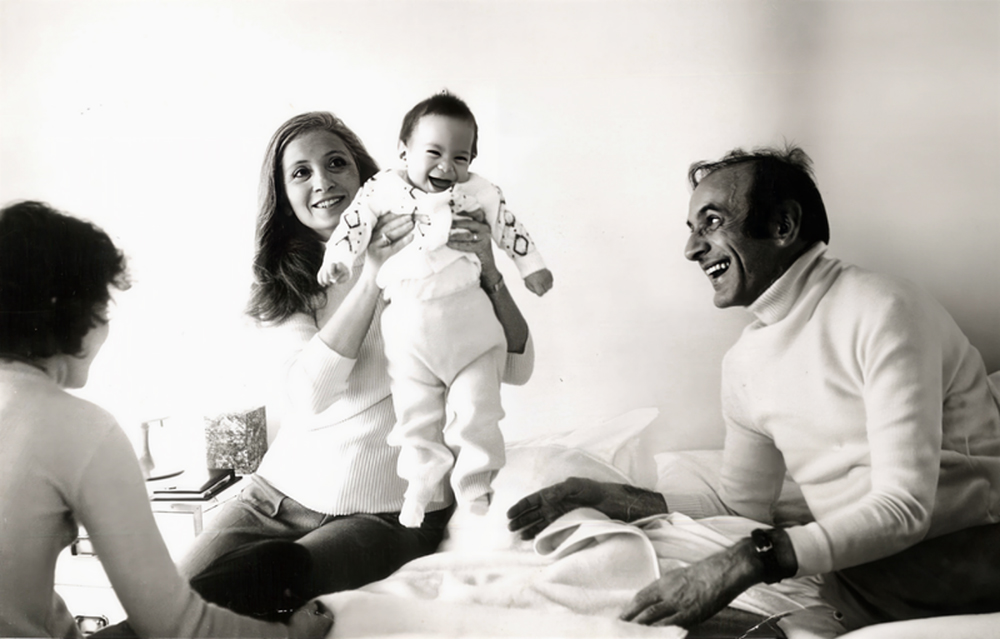

Much of the film, which incorporates dreams and emotional imagery, focuses on Wiesel and his family: his wife, Marion, who translated many of his books, and who died in February at age 94; and his only child and son, Elisha, 52.

It also depicts the elder Wiesel’s relationship with Israel. His son said his father traveled to Israel during every war through 2014, standing by the Jewish state.

One poignant moment shows Elisha reading a letter his father wrote to him in 1991 with final words in case he perished in the Israeli bomb shelter as Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein’s Scud missiles flew overhead.

“ … Remember my father, after whom you have been named,” Elisha Wiesel reads in the film. “Remember what you are, a Jew. That even within doubt, there is a God, the God of Israel. Take care of yourself. You have been and remain the center of my life.”

The documentary comes out at a time of growing antisemitism, when the word “Zionism” has become a slur on college campuses, online and in other arenas.

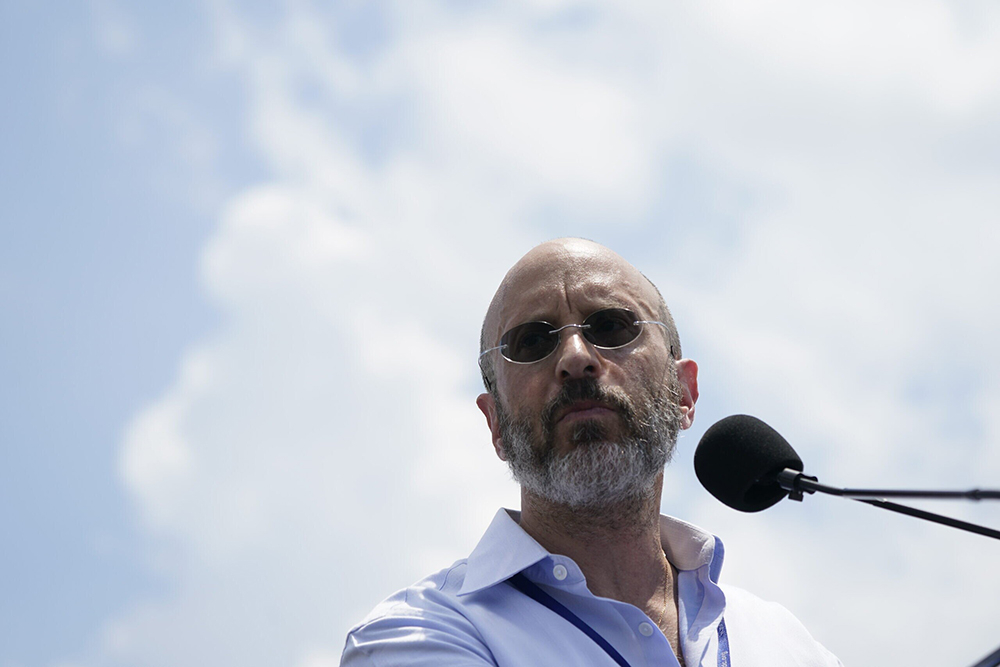

“With Jewish people worldwide experiencing more hatred than I can remember in my lifetime, to have a documentary about a prominent American Jew, a beloved leader who was a prominent Zionist, is very important,” Elisha Wiesel told JNS. “My hope is that it could rekindle the love for Israel and inspire younger audiences who have not discovered him.”

Elisha Wiesel has gone on several news channels to explain how Israel has not committed a genocide against Palestinians in Gaza, where the Israel Defense Forces have been fighting following the Hamas-led terrorist attacks in southern Israel on Oct. 7, 2023.

‘He had a calling’

The film’s director, Oren Rudavsky, said it was important to show Wiesel’s combination of humility and conviction, particularly as a public speaker and authentic progenitor of history. Footage shows Wiesel, in a speech broadcast on NBC, telling U. S. President Ronald Reagan in 1985 that it would be a mistake to visit the Bitburg cemetery in Germany. Reagan had agreed to visit, only to learn that more than 30 Waffen-SS graves were there.

Asked by a reporter if Wiesel was giving the president a moral lesson, he simply replied that he was a “storyteller.”

Why did he write? “What else could I do?” he stated, plaintively, in his own voice in the film. “I write to bear witness.”

Rudavsky told JNS that it is “implicit in the film that we need leaders like Elie Wiesel, gentle but forceful, at a time when people speak in a way he would have never spoken. Jews in the world community from all sides need to find common ground; we are going through horrific times, and many want to divide the Jewish people. We need to find a way to speak for what is best not only for Judaism, but for humanity.”

Referencing Wiesel, he added: “I think he would have sought to unify people, even if we believe different things.”

The film, with its hand-painted animation, shows Wiesel speaking about the horror of war over the years, and the suffering of Israelis and Palestinians, while his wife notes that her husband was reluctant to criticize Israel.

Co-producer Anette Insdorf, a daughter of Holocaust survivors, is an author and movie critic who has taught film at Columbia University since 1987. She has served as moderator of the 92 Street Y’s longest-running interview series, called “Reel Pieces.” Insdorf said she valued Wiesel’s friendship. She offered assistance to Elisha as a slew of requests were made for materials to make a documentary about his father. As for Rudavsky, she noted being impressed by his 2004 film “Hiding and Seeking: Faith and Tolerance After the Holocaust.”

She said points of animation help make the film poetic, rather than a series of talking heads. For someone so accomplished and well-known, Wiesel spoke in a soft voice and showed little ego. In that way, he had the capacity to cause others to listen.

“I think it had to do with his profound sense of gratitude and moral clarity,” Insdorf told JNS. “I think he learned in his younger years not to sweat the small stuff. He had a calling. He never raised his voice when speaking to people. He was brilliantly poised in a way that was quite unusual.”

‘The legacy is huge’

It is a mystery as to how Wiesel was able to write so much (57 books, mostly in French and English) and so well, given the trauma of what he saw during his time in Auschwitz, which included the normalcy of waking up and going to sleep next to corpses.

His parents did not survive the Holocaust—his mother, Sarah, and 7-year-old younger sister, Tzipora, were both murdered in Auschwitz upon the family’s arrival in May 1944; his father, Shlomo, died in Buchenwald of dysentery in January 1945, following the march from Auschwitz. He has said that it was his father who kept him alive during that awful time: “We saw it together. I knew that if I died, he would die.”

Had Wiesel not spoken to the media in his eloquent and calm fashion, could that have deterred other survivors from speaking out? Rudavsky and Insdorf said that while that question is difficult to answer, it laid the groundwork for others, as well as for many related educational paths.

“Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire” doesn’t delve into the Holocaust survivor’s many writings or his work in attempting to free Soviet Jewry, which occupied decades of his life in the latter part of the 20th century.

“The legacy is huge, so that’s the challenge,” Rudavsky said. “You run the risk, if you tell everything, of telling nothing. My goal was to get to the heart of who this amazing man was.”

Elisha Wiesel said his father would not let Night be made into a film. It has remained in literary circles and school reading. The documentary shows students in Newark, N. J., discussing the book and its lessons.

What advice did he give his son when it came to a future occupation?

“My father gave me clear instructions at an early age when I was still trying to figure out my career,” Elisha Wiesel said. “He said, ‘Whatever you do, don’t become a rabbi.’ He amended it and said not to get involved in Jewish communal leadership. He wanted me to flourish in whatever I gravitated to.”

The film also touches upon the generation of Germans beyond the Nazi period and associated guilt. The guilt of the aggressor weighed on the guilt of the survivor. Wiesel said it stopped there; that there must be a way to live on free to choose a better destiny for both.

Insdorf reaffirmed that, noting that Wiesel said children of Nazis should not feel guilt for the transgressions of their parents and grandparents.

Over the years, much work has been accomplished in that regard, specifically between Germany and Israel.

To that end, the film shows several grandchildren of Wiesel, who said that they felt pressure to do something great, like their grandfather.

Insdorf also said Wiesel loved teaching, mostly at Boston University, and believed that there was great power in preparing the next generation.

“He taught that the opposite of love is not hate,” Insdorf said. “It’s indifference.”

(JNS. org)

“Soul on Fire” opens at the IFC Center in New York City on Sept. 5.