|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Edited by: Fern Sidman

In late June, the French National Assembly gathered to take a historic step toward acknowledging and rectifying a dark chapter in the nation’s history, according to a recent report on the ARTNews.com web site. The agenda included a vote on a groundbreaking bill aimed at facilitating the return of artworks stolen from Jewish families during the Nazi era. The unanimous approval of this legislation marked a significant moment in France’s willingness to confront its painful past, as was reported by ARTNews.com

The unanimous approval of the art restitution bill in France’s National Assembly was a momentous occasion. For a country that has often struggled to come to terms with its complex history, especially regarding its role during the Holocaust, this decision represented a significant leap forward, as was noted in the ARTNews.com report. It was an acknowledgment of the government’s involvement in the systematic theft of Jewish belongings during the Nazi era, alongside Nazi Germany.

The new law is far-reaching, as it enables the return of stolen art, books, and cultural property from France’s public domain, even if it was looted beyond the country’s borders. The ARTNews.com report indicated that in the past, such restitution claims had to navigate a lengthy and challenging process, with case-by-case deaccessioning laws being the norm. ARTNews.com also reported that this legislation streamlines the process and acknowledges the importance of returning stolen items to their rightful owners.

While the passing of this law is a major step forward, it comes nearly 80 years after the end of World War II. However, it is worth noting that most countries have yet to take similar measures. The ARTNews.com report said that France joins the ranks of Austria, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Germany in having a dedicated commission for the restitution and research of Nazi-looted art.

The reluctance to address the issue of restitution for so long can be attributed, in part, to the complexities surrounding Nazi plundering and the passage of time. As was noted in the ARTNews.com report, France, like many other Western European countries, had its share of looted artworks, with estimates suggesting over 100,000 items were taken from Jewish collections. These items included works sold under duress by families seeking to escape persecution, as well as those auctioned by government-appointed administrators overseeing seized Jewish property, the report added. France did eventually return a significant number of artworks, but thousands remained unclaimed and were eventually housed in public museums.

The “silent years” or “trente silencieuses” referred to the decades following the 1950s, during which only a few MNR artworks were restituted because institutions did not actively seek out the owners, as was mentioned in the ARTNews.com report. This era of indifference finally ended when journalist Hector Feliciano published “The Lost Museum” in 1995, shedding light on Nazi looting and MNRs (National Museums Recovery registry).

France’s approach to restitution has evolved over the years, with a growing awareness of the need for transparency and justice. ARTNews.com also reported that the establishment of commissions dedicated to researching Nazi-looted art and the government’s efforts to identify and return unclaimed MNR artworks have been significant milestones. French institutions have also begun hiring researchers dedicated to provenance issues, signaling a shift in mindset and a commitment to addressing the problem.

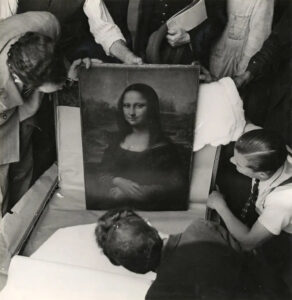

Emmanuelle Polack’s appointment as an art historian coordinating provenance research at the Louvre in 2020 exemplifies this change. ARTNews.com reported that she has been actively involved in identifying questionable dealers and signs of plundered Jewish collections in the museum’s acquisitions during the Nazi era. Younger generations have shown a desire for transparency and provenance information in museums, pushing institutions to be more forthcoming about their collections’ histories, the report added.

While the new Nazi restitution law is a step in the right direction, it is just the beginning of a broader effort to address France’s complicated past. As was reported by ARTNews.com, the government plans to pass two more “framework” restitution laws, one dealing with the repatriation of human remains and the other addressing the repatriation of art taken during the colonial era.

The latter, in particular, is expected to face significant debate and challenges. France’s colonial history is a highly sensitive and divisive issue, and there is concern that acknowledging wrongdoing in the context of the country’s vast colonial empire could lead to further complications, according to the ARTNews.com report. The lack of consensus on condemning French colonial actions might create a perception of double standards and division within communities.

France’s landmark art restitution law represents a significant milestone in the nation’s journey toward acknowledging and rectifying the injustices of the past. It reflects a growing awareness of the need for transparency and justice regarding Nazi-looted art and stolen cultural property. While there are challenges on the horizon, particularly regarding restitution from former colonies, the passage of this law sends a strong message that President Emmanuel Macron is addressing the scrutiny of museum acquisitions and fostering a culture of transparency and restitution. It is a critical step toward recognizing and honoring the memory of those who suffered during the Holocaust and other dark chapters in history, ensuring that such atrocities are not forgotten or repeated.