|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Fern Sidman

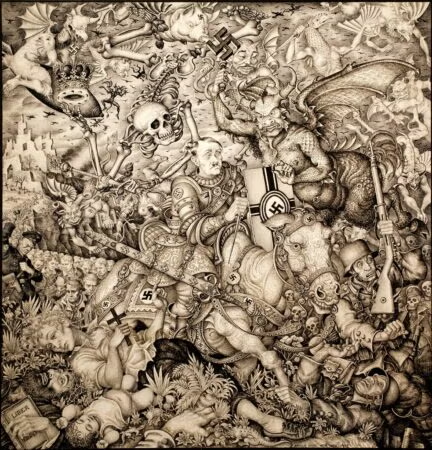

When visitors step into the Museum of Jewish Heritage — A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, they are not greeted by quiet reflection, but by a thunderclap. Looming across an entire wall is a nine-inch square work, explosively enlarged, from 1942: Arthur Szyk’s Anti-Christ, a ferocious miniature that The New York Times described as both “bestiary” and indictment. Swastika-bearing vultures descend upon the innocent; skeletal gallows twist across the horizon; Adolf Hitler’s eyes gleam with tiny skulls. To stand before the piece is to confront, without anesthetic, the moral voltage of an artist who insisted that drawing was a form of combat.

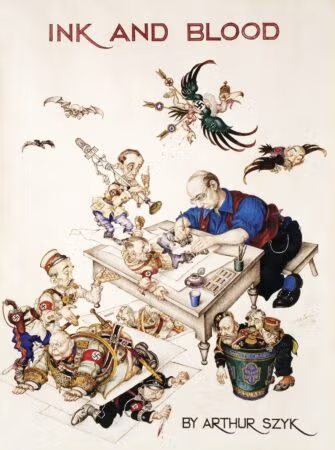

It is an arresting introduction to “Art of Freedom: The Life and Work of Arthur Szyk,” an expansive new exhibition that opened Sunday at the downtown museum. According to a report that appeared on Thursday in The New York Times, which detailed the exhibition’s scope and its remarkable trove of rediscovered works, the show represents a pivotal moment in the revival of an artist who once achieved global celebrity, only to fall into decades of near-total obscurity.

But this exhibition is more than a museum retrospective. It is an argument, one delivered with the urgency of sirens: that art is a form of witness, that historical amnesia is perilous, and that culture itself may yet serve as a bulwark against the rising tides of hatred.

And at the center of the exhibition’s genesis is a deeply personal act of philanthropy — a gift made by Sindy Liben in memory of her late husband Barry H. Liben, z”l, a prominent and well-respected businessman (who was chairman of the conglomerate Tzell Travel Group). Their contribution of four Arthur Szyk works, purchased from the leading Szyk authority and collector Irvin Ungar, catalyzed the Museum of Jewish Heritage’s decision to launch what has become the most ambitious Szyk exhibition in a generation.

Arthur Szyk (pronounced “Shik”) described himself not as a painter or cartoonist, but as “a Jew praying in art.” Yet his prayers were hardly silent. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, his illustrations — equal parts medieval illumination, modern political cartoon, and incandescent prophetic rage — became some of the most widely reproduced anti-Nazi images in the West. According to the information provided in The New York Times report, American GIs treasured Szyk’s caricatures more than pinups, and Eleanor Roosevelt used her newspaper column My Day to declare that Szyk “fights the Axis as truly as any of us who cannot actually be on the fighting fronts.”

His work found its way into Collier’s, the Chicago Sun, PM, and The New York Post. His targets included Hitler, Goebbels, Mussolini, and Japanese militarists — all rendered in grotesque, medieval-inspired detail that turned propaganda into moral theatre.

But the new exhibition emphasizes that Szyk was far more than Roosevelt’s “soldier in art.” He was an illuminator of sacred texts, a miniaturist of astonishing discipline, a chronicler of American democracy, a portraitist of Revolutionary figures, and — as the Times noted — a forerunner to Ken Burns in his popularization of the American founding.

The seeds of the exhibition were planted not in a boardroom but in the home of Sindy Liben, who approached the museum last year with an offer to donate four original Szyk works from the couple’s collection. Her husband, Barry Liben, who passed away in 2020, had been an avid supporter of Jewish education, Israeli causes, and Jewish culture. His passion for Judaic artwork and manuscripts reflected his lifelong devotion to Zionist activism and Jewish continuity.

Barry Liben was not only a major American Jewish philanthropist but also a committed leader in the Betar Zionist youth movement, serving as national director in the 1970s — a formative era in which he shaped a generation of young Jewish activists committed to Israel’s security and cultural resilience. His dedication to Jewish causes spanned philanthropy, community leadership, and a deep personal engagement with Jewish history and identity. The Libens’ commitment to preserving and uplifting Jewish artistic heritage made their donation especially resonant for a museum devoted to historical memory.

Among the donated works were “Modern Moses” (1943) — a stirring image of Moses locking arms with Jewish resistance fighters — and a rare 1930s black-and-white poster commemorating a 1920 battle between Jewish settlers and Arab militias. These pieces, brimming with moral urgency, became the cornerstone around which the exhibition was built.

Jack Kliger, the museum’s president and CEO, told The New York Times that once the Liben pieces arrived, it became clear the museum had an opportunity — even an obligation — to mount a full-scale reconsideration of Szyk’s oeuvre. The Liben family’s gift became the catalyst for curatorial ambition.

Central to the exhibition is the extraordinary personal archive of Irvin Ungar, a rabbi turned antiquarian bookseller whose nearly half-century obsession with Szyk borders on the monastic. Ungar provided 35 of the 39 works featured in the exhibition, including a recently rediscovered sketchbook from Paris circa 1928 — a revelation in understanding how Szyk prepared his Revolutionary War illustrations and caricatures.

Ungar’s devotion began, as he told the Times, 50 years ago when he saw a 1956 reproduction of Szyk’s Haggadah in a Manhattan bookstore while searching for wedding gifts. That spark grew into a consuming vocation. Ungar mortgaged his home to amass Szyk’s scattered works — many from Szyk’s daughter, Alexandra Braciejowski — and published scholarship that helped thrust Szyk back into scholarly view.

His forthcoming book, Reviving the Artist Who Fought Hitler: My Life with Arthur Szyk, is expected in 2026.

While Szyk’s wartime caricatures are the most explosive works in the exhibition, the show’s intellectual power lies in its breadth.

Szyk’s style — ornate borders, jewel-toned colors, gilded flourishes — drew deeply from medieval manuscripts, Mughal miniatures, and illuminated Bibles. His miniatures were painstaking, often requiring magnifying lenses and months of labor. His illuminated Declaration of Independence from 1950, nearly two-by-three feet, stands as his largest work on paper and one of his most visually arresting.

He illustrated the stories of Job, Esther, Ruth, the Song of Songs, and the Ten Commandments — not as distant biblical folklore but as moral arguments for justice, survival, and human dignity. In his Passover Haggadah — priced at an astonishing $520 in 1940, nearly the cost of a car — he famously inserted swastikas into the clothing of ancient Egyptians before publishers made him remove them. Even in sacred texts, he refused to blunt contemporary relevance.

Szyk’s affection for America — particularly its founding ideals — is palpable. His series Washington and His Times, produced in the early 1930s, so impressed political leaders that the president of Poland later purchased them for Franklin D. Roosevelt, who hung them in the White House.

The New York Times report noted that the exhibition includes the sketchbook that preceded these works, offering insight into Szyk’s meticulous study of Revolutionary uniforms, insignia, and weapons.

Despite his anti-Nazi achievements, Szyk was not spared suspicion during the anti-Communist hysteria of the 1950s. The House Committee on Un-American Activities associated him with several supposedly subversive groups — a bitter irony for a man who had spent a decade producing patriotic American art. He died suddenly in 1951, at age 57, before the cloud could be lifted.

Born in 1894 in Łódź, then under Russian rule, Szyk was the son of a middle-class Jewish family descended from rabbis. He studied at the Académie Julian in Paris, toured the Middle East in 1914, witnessed Zionist pioneers firsthand, and survived World War I as a reluctant conscript in the Russian army.

His life was split between creation and catastrophe. As The New York Times reported, he never learned the full fate of his own family during the Holocaust. In 1942, Nazis deported his mother, Eugenia, his brother, Bernard, and their Polish maid, Josefa, to Chelmno, where they were murdered.

His grief only intensified his artistic ferocity.

The exhibition arrives at a moment when antisemitism, nationalism, and authoritarian impulses are again on the rise — in the United States and globally. The New York Times report argued that Szyk’s revival is especially timely, offering a visual vocabulary for confronting tyranny, demagoguery, and moral inversion.

Bruce Ratner, chairman emeritus of the museum and one of the exhibition’s strongest champions, emphasized Szyk’s antifascist message as central to its relevance, as was reported by The New York Times. Ratner has long argued that art is a powerful tool against historical amnesia — and that Szyk, in particular, forces viewers to confront hatred head-on.

Sara Softness, the exhibition’s curator, described Szyk as “a person of the world, with allegiance to many nations, religions and forms of justice advocacy,” whose art is a parable for the present.

From the Forest Hills Torah ark — a monumental 30-foot creation — to the illuminated founding documents, to the Haggadah that once cost more than a family car, Szyk’s work argues that beauty can be a weapon and that detail can be a form of devotion.

His fall into obscurity after his death represented not merely the loss of a great Jewish artist but the severing of a key thread in American cultural history. Thanks to the scholarship of Irvin Ungar, the curatorial insight of the Museum of Jewish Heritage, and the generosity of Sindy Liben and the late Barry H. Liben, z”l, that thread has been rewoven.

In an era in which historical truth is contested and antisemitic rhetoric has resurfaced in mainstream political spaces, Szyk’s images feel less like artifacts and more like warnings. The New York Times report suggested that the exhibition’s power lies in this duality: it celebrates a master of miniature art while sounding an alarm about the very forces he fought.

The exhibition closes not with a whisper but with an embodied argument: that memory is an act of resistance, that beauty can be a shield, and that art is both a refuge and a form of battle.