|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Justin Winograd

In an era when masterpieces by Pablo Picasso routinely fetch eight-figure sums behind velvet ropes and discreet paddle raises, the notion that one of his works could change hands for the cost of a modest dinner seems almost absurd. Yet that is precisely the paradox animating a remarkable charitable initiative now capturing the attention of the global art world. As The New York Post reported on Sunday, a Picasso painting valued at approximately $1.1 million will be awarded not through a traditional auction, but via a raffle—an audacious blend of high culture, philanthropy, and chance that has few modern precedents.

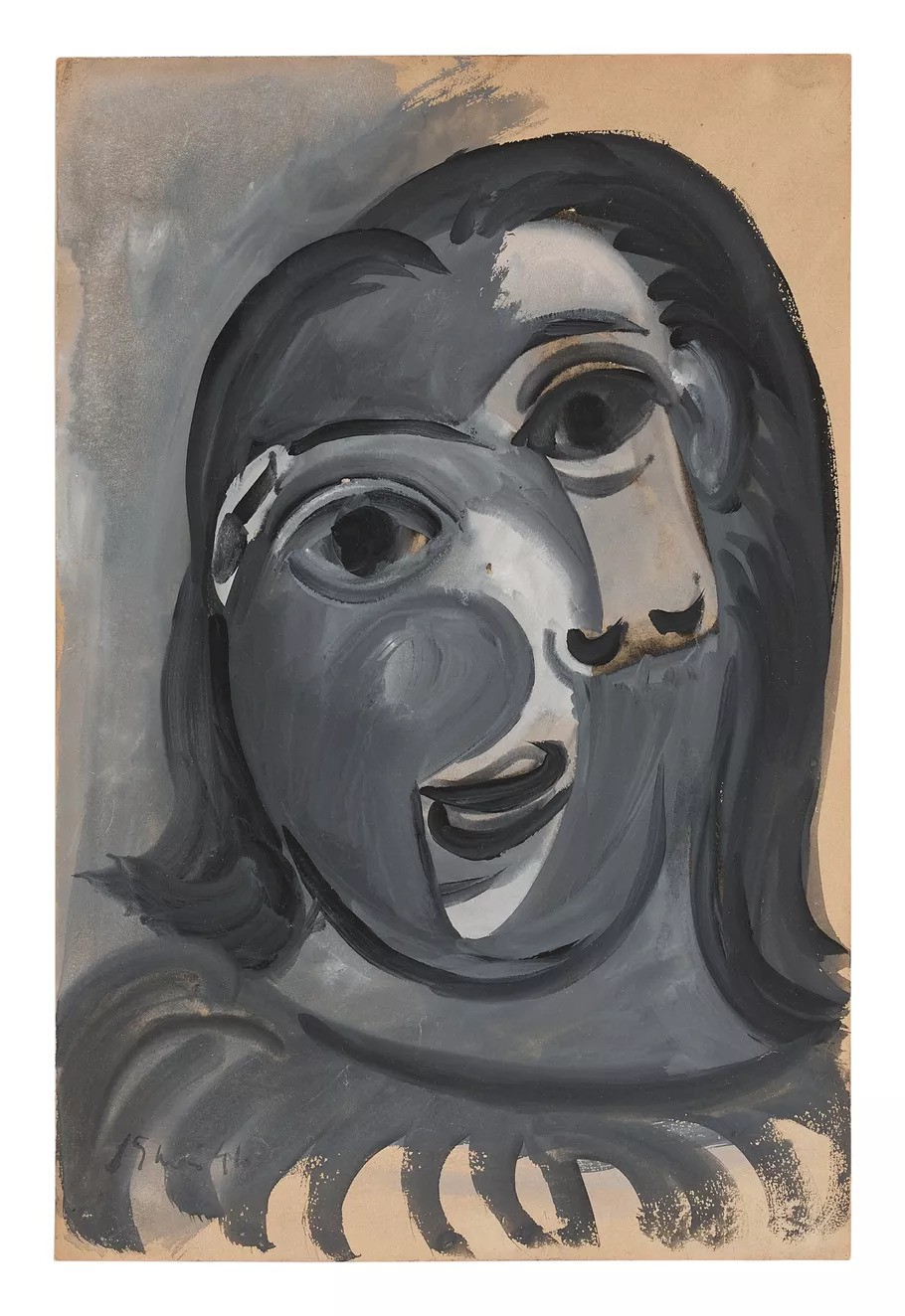

The artwork in question, Tête de Femme (1941), a gouache-on-paper portrait created during one of the most emotionally and historically fraught periods of Picasso’s life, will be handed over to a single lucky ticket holder at a fundraising event benefiting Alzheimer’s research. Tickets, priced at roughly $117, are being sold worldwide by the Fondation Recherche Alzheimer, the French research foundation organizing the event, which is scheduled to culminate on April 14 at Christie’s in Paris. As The New York Post report noted, approximately 120,000 tickets will be offered globally, with participants able to attend the drawing either in person or online.

At first glance, the idea sounds almost too good to be true: a masterwork by one of the twentieth century’s most influential artists, acquired not by hedge fund magnates or museum boards, but by an ordinary individual armed with little more than hope and a three-digit ticket. But organizers insist the mechanics are sound, the security airtight, and the cause unimpeachable.

According to the information provided in The New York Post report, the foundation plans to use ticket proceeds to cover the $1.1 million acquisition cost of the painting and still net more than $12 million to fund critical Alzheimer’s research. If ticket sales fail to meet the required threshold, the foundation has pledged to cancel the raffle entirely and reimburse all participants—a safeguard designed to maintain transparency and public trust.

The drawing itself will be conducted under tight security at Christie’s, one of the world’s most venerable auction houses, lending institutional gravitas to an otherwise unconventional format. The presence of security personnel and oversight mechanisms underscores the seriousness with which organizers are treating the event, even as its premise invites a sense of whimsy and wonder.

Tête de Femme was painted in 1941, a year that found Picasso living under the shadow of Nazi-occupied Paris and navigating profound personal strain. The work depicts a woman’s head rendered with the angular distortions and emotive intensity characteristic of Picasso’s wartime output. According to Artsy, cited in The New York Post report, the portrait emerged during a difficult period in Picasso’s relationship with his first wife, Olga Khokhlova, adding a layer of biographical poignancy to its aesthetic power.

Art historians have long regarded Picasso’s wartime works as a crucible of experimentation and emotional depth. While Guernica remains the most iconic product of this era, smaller works like Tête de Femme offer an intimate window into the artist’s psyche—a blend of defiance, despair, and relentless creativity amid external chaos.

Oliver Picasso, the artist’s grandson, believes the portrait was painted in the same Paris studio where Picasso worked on Guernica, according to comments he made to The New York Times and referenced by The New York Post. That geographical and temporal proximity to one of the twentieth century’s most important artworks only heightens the painting’s historical resonance.

For the Picasso family, the raffle represents more than a novel fundraising tactic; it is framed as a continuation of the artist’s personal ethos. “Associating the name of Pablo Picasso to charity, a charitable purpose, is very important because my grandfather was very generous with the people around him,” Oliver Picasso told The New York Times.

That sentiment is not merely rhetorical. Picasso, despite his reputation for mercurial temperament, was known to support friends, lovers, and causes he deemed worthy, often through informal patronage. In this sense, the raffle is positioned as a modern extension of that spirit—leveraging the enduring power of his name and work to address one of the most devastating diseases of our time.

Central to the project is Peri Cochin, a longtime friend of Olivier Picasso and a seasoned organizer of similar initiatives. As The New York Post report detailed, Cochin helped the foundation secure Tête de Femme from the Opera Gallery for $1.1 million. She has also played a pivotal role in organizing two previous Picasso raffles, one in 2013 and another in 2020, both of which successfully combined art philanthropy with global participation.

Those earlier raffles offer compelling precedents. In 2020, for example, the winning ticket went to an Italian accountant who had received it as a Christmas gift from her son—a detail that The New York Post report highlighted as emblematic of the raffle’s democratic allure. Such stories reinforce the idea that this is not merely an exercise in spectacle, but a genuine attempt to broaden access to cultural capital while advancing a humanitarian mission.

The initiative has inevitably sparked debate within art circles. Purists question whether raffling a masterpiece risks trivializing the seriousness of fine art, reducing it to a lottery prize. Others counter that the traditional auction system already privileges wealth over merit, and that a raffle—particularly one tied to medical research—offers a refreshing alternative.

The New York Post report framed the event less as a subversion of art market norms and more as a clever circumvention of them. By replacing exclusivity with inclusivity, the raffle invites tens of thousands of people to imagine themselves not merely as spectators, but as potential custodians of cultural heritage.

Moreover, the charitable dimension complicates any critique rooted in market orthodoxy. Alzheimer’s disease, a neurodegenerative condition affecting millions worldwide, remains one of the most urgent public health challenges of the twenty-first century. The Fondation Recherche Alzheimer argues that if a Picasso raffle can accelerate scientific breakthroughs, then the unconventional means are more than justified.

Operationally, the raffle is structured to maximize accountability. Tickets must be purchased directly through the foundation, reducing the risk of fraud. Participants from around the world can follow the drawing online, ensuring visibility and engagement across borders. Security protocols at Christie’s will further safeguard the integrity of the process, a point emphasized repeatedly in The New York Post’s coverage.

The foundation’s contingency plan—full reimbursement if ticket sales fall short—adds another layer of reassurance. In an age when charitable scandals have eroded public confidence, such measures are not merely prudent; they are essential.

Beyond the mechanics and the money, the raffle captures a broader cultural moment. It reflects a growing appetite for initiatives that blur the boundaries between elite institutions and public participation, between high art and popular engagement. It also speaks to a renewed emphasis on social responsibility within the cultural sector, where prestige is increasingly tied to purpose.

As The New York Post report observed, there is something irresistibly cinematic about the premise: a priceless Picasso, a $117 ticket, and the possibility that an ordinary person could wake up the next morning as the owner of a museum-worthy masterpiece. Yet beneath the romance lies a serious ambition—to harness that sense of possibility in service of scientific progress.

When the drawing takes place on April 14, the winner will receive more than a painting. They will inherit a fragment of twentieth-century history, a testament to artistic resilience under oppression, and a tangible symbol of philanthropy’s potential to innovate. Whether the raffle ultimately becomes a model for future fundraising or remains a singular experiment, it has already succeeded in one respect: capturing the imagination of the world.

In chronicling this extraordinary convergence of art, chance, and charity, The New York Post has underscored a simple yet profound truth. Sometimes, the most meaningful cultural moments are not forged in hushed auction rooms or behind closed doors, but in bold gestures that invite the many, rather than the few, to take part.