|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Edited by: Fern Sidman

Switzerland’s reckoning with its Nazi-era financial dealings, a chapter many thought was closed after the restitution payments of the 1990s, has been thrown into question by explosive new findings. According to a recently published report in The Wall Street Journal, independent investigators have uncovered a trove of damning documents in Credit Suisse’s archives, revealing previously undisclosed accounts tied to high-ranking Nazi officials and a troubling pattern of apparent cover-ups by the bank.

In the 1990s, Swiss banks were placed under global scrutiny for their role in handling looted assets and funds belonging to Holocaust victims. Following widespread outrage and intense investigations, Switzerland’s two largest banks ultimately agreed to a historic $1 billion restitution settlement. However, the WSJ reported that this effort, once thought to have brought closure, now appears to have been incomplete, if not partially orchestrated as a whitewash.

The latest revelations stem from an investigation led by Neil Barofsky, a former U.S. prosecutor and partner at the law firm Jenner & Block. Barofsky was initially hired by Credit Suisse in 2021 after the Simon Wiesenthal Center flagged evidence suggesting the bank had not fully disclosed all accounts linked to Nazi clients. As the WSJ report explained, investigators painstakingly sifted through dusty ledgers and microfilm reels previously excluded from the earlier probes, ultimately uncovering what could only be described as signs of an institutional cover-up.

One of the most damning discoveries, the WSJ revealed, is a cache of client files labeled “American blacklist.” These files flagged accounts associated with individuals and entities financing or trading with Nazi Germany and Axis powers. Investigators also uncovered an operational account allegedly managed by high-ranking Nazi SS officers and a Swiss intermediary. According to the report in the WSJ, this account appears to have been used to move and store looted assets, further implicating the bank in enabling Nazi financial operations during and after the war.

In the 1990s, two independent panels were tasked with scrutinizing Swiss banks’ World War II-era activities. Yet, as the WSJ report highlights, crucial details about these accounts and their beneficiaries were deliberately withheld from those investigations. While Credit Suisse had knowledge of certain Nazi-linked accounts at the time, it failed to disclose them, raising serious ethical and legal concerns about the integrity of the bank’s cooperation.

The investigation took a tumultuous turn in 2022 when Credit Suisse abruptly dismissed Barofsky from his oversight role. Bank executives reportedly accused him of overstepping boundaries they had imposed on the probe. However, as the WSJ report explained, Barofsky’s dismissal caught the attention of the U.S. Senate Budget Committee, which intervened due to its oversight of the State Department’s Office of the Special Envoy for Holocaust Issues. This office plays a critical role in securing justice and compensation for Holocaust victims and their families.

Barofsky was reinstated in late 2023 following UBS’s emergency acquisition of Credit Suisse. In a letter sent to the Senate Budget Committee in December 2024 and reviewed by The Wall Street Journal, Barofsky detailed the ongoing investigation’s progress. He emphasized that Credit Suisse, now under UBS ownership, has fully opened its archives and assigned over 50 staff members to support the investigation.

According to the WSJ report, Barofsky’s letter described “scores of individuals and legal entities connected to Nazi atrocities whose relationships with Credit Suisse had either been previously unidentified, or for which the relationship had been partially identified but the full nature of the bank’s involvement has not yet been reported publicly.”

These revelations have reignited global outrage and prompted renewed calls for accountability, not only from the bank but from Switzerland’s financial regulators and government institutions. As The WSJ report points out, this investigation is not merely about historical reckoning—it’s about long-overdue transparency and justice for the victims and their descendants who suffered at the hands of a brutal regime, enabled in part by financial complicity.

The implications of these findings extend far beyond Credit Suisse. They raise troubling questions about how deeply entrenched financial institutions were in Nazi-era operations and whether other banks have similarly buried their culpability. The WSJ reported that stakeholders are calling for enhanced oversight of archival materials held by Swiss banks and for continued transparency in resolving these long-standing injustices.

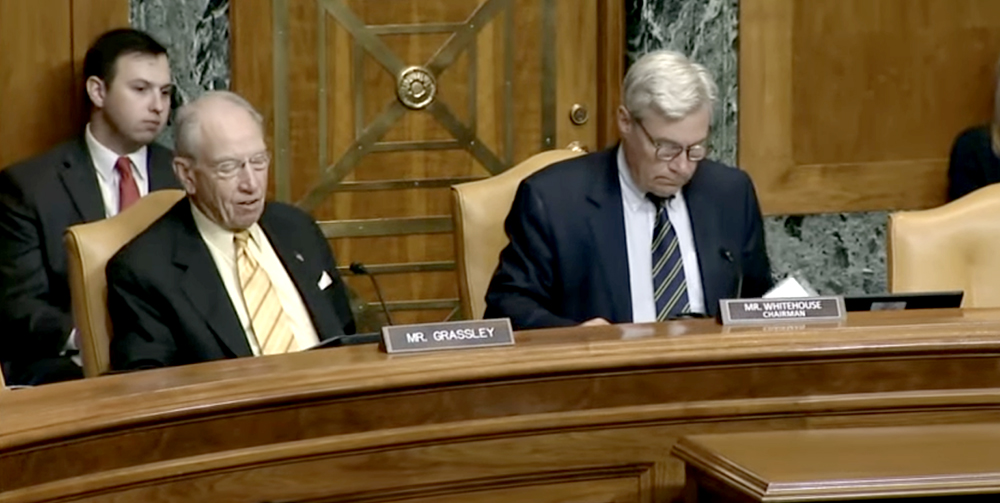

A spokesperson for UBS told the WSJ: “UBS is committed to contributing to a fulsome accounting of Nazi-linked legacy accounts previously held at predecessor banks of Credit Suisse.” This declaration comes after a Senate investigation led by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D., R.I.) and Sen. Chuck Grassley (R., Iowa) intensified scrutiny over Credit Suisse’s apparent efforts to obscure its historical ties to Nazi finances.

Sen. Grassley was particularly direct in his criticism, telling The Wall Street Journal: “Credit Suisse hid additional evidence of Nazi ties for years, and even tried to conceal information from our congressional investigation.”

As was detailed in the WSJ report, recent photos from one of the bank’s archives in Zurich offer a stark visual representation of the scale of the investigation. Entire rooms are filled with towering pallets of boxes stacked floor to ceiling, along with ledgers, computers, and hard drives—all holding client records spanning decades. Within this trove lie 3,600 boxes from what is referred to as the “Inf department.”

This department, as the WSJ report explained, was responsible for “know your customer” details—records banks keep on their clients to understand their financial behavior and affiliations. A preliminary search of these archives against a list of 99 known Nazi figures and affiliates produced 13 name matches, a discovery described as deeply concerning by Neil Barofsky.

Shockingly, the WSJ report revealed that portions of these files had been reviewed during earlier investigations in the 1990s but were neither scanned nor systematically indexed, rendering them effectively invisible to auditors. Barofsky’s team is now undertaking the monumental task of processing these records comprehensively for the first time.

While conducting interviews with former Credit Suisse employees involved in the 1990s investigations, Barofsky discovered indications that the bank deliberately withheld key information. According to The Wall Street Journal, internal comments from bank executives on one of the 1990s investigation panel’s draft reports described the findings as “rather sanitized” but recommended leaving them as is.

Former employees disclosed that Credit Suisse’s general approach was to share only what external investigators explicitly requested, without volunteering additional information or context. This policy of selective transparency allowed critical details to remain hidden—including evidence tied to an account allegedly controlled by SS officers and a Swiss intermediary.

As the WSJ recounted, businesses connected to this account were reportedly instrumental in furthering the Nazi regime’s economic goals. They seized Jewish-owned businesses, laundered stolen wealth, and utilized forced labor from concentration camps.

One of the most troubling discoveries in the recent investigation, according to the report in the WSJ is a registry card tied to the SS-linked account. The card was initially discovered in the 1990s and flagged to higher-ups within Credit Suisse. However, bank historians at the time failed—or perhaps refused—to associate the registry card with the account in question.

The WSJ reported that as recently as April 2023, Credit Suisse continued to claim that this connection had not been identified during previous reviews. These repeated oversights—or deliberate omissions—paint a picture of a bank that prioritized protecting its reputation over reckoning with its troubling past.

The Senate Budget Committee, which has jurisdiction over the State Department’s Office of the Special Envoy for Holocaust Issues, remains deeply engaged in overseeing this probe. As The Wall Street Journal report indicated, this office is responsible for securing compensation and justice for Holocaust victims and their descendants. The implications of the investigation’s findings could lead to renewed demands for restitution and accountability measures from UBS.

The fallout from this investigation is not confined to historical inquiry—it raises contemporary questions about corporate responsibility, transparency, and the ethical obligations of financial institutions. As the WSJ report noted, UBS is now under immense pressure to ensure that this investigation is carried out thoroughly and transparently.

In 2001, when asked directly by one of the panels established to investigate wartime accounts, Credit Suisse claimed it had no documentation indicating a business relationship with the SS holding company. This statement, WSJ reported, led the panel to conclude that any relevant records must have been destroyed. However, recent findings suggest otherwise, indicating that documents did exist but were either withheld or overlooked during those investigations.

The revelations come nearly three decades after the first major international outcry over Swiss banks’ role in hiding Holocaust victims’ assets erupted in the mid-1990s. As the WSJ report explained, two landmark investigations were launched in response. The first was led by Paul Volcker, former chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, and focused on dormant or looted accounts linked to Holocaust victims. Auditors under Volcker’s oversight dove deep into bank archives in an attempt to trace these financial connections.

The second investigation, organized by the Swiss parliament and headed by historian Jean-François Bergier, conducted a broader inquiry into Switzerland’s financial and economic relationship with Nazi Germany. According to WSJ, both panels concluded that Swiss bankers had routinely turned a blind eye to the Nazi theft of Jewish assets during the war and, disturbingly, often obstructed families’ attempts to reclaim their rightful funds in the decades that followed.

However, neither panel claimed to provide a comprehensive accounting of all wartime accounts or a definitive record of every instance of wrongdoing. As the report in the WSJ emphasized, both investigations had limitations, including reliance on the banks’ willingness to share information openly—a willingness now in question given the recent discoveries.

During the initial 1990s investigations, Credit Suisse reported identifying 14 accounts believed to have been held by Nazi clients. UBS, Switzerland’s other banking giant, said it had found one account belonging to a former Reichsbank president and another linked to the widow of an SS officer, which was opened decades after the war.

In response to these findings, and under intense international pressure, the two banks agreed to a landmark settlement in 1998. As the report in the WSJ recounted, they paid $1.25 billion to Holocaust survivors, the families of Jewish account holders who had been denied access to their funds, and the descendants of slave laborers who had been exploited by the Nazi regime. Many Jewish organizations at the time supported the settlement, viewing it as a significant step toward justice, if not a fully exhaustive resolution.

Yet the recent revelations suggest that the settlement, while symbolically and materially meaningful, may not have been built on a foundation of complete transparency. As The Wall Street Journal noted, the gaps in Credit Suisse’s disclosures—and the discovery of previously undisclosed Nazi-linked accounts—are deeply troubling.

The ongoing investigation, led by former U.S. prosecutor Neil Barofsky, is tasked with revisiting the murky past of Credit Suisse and its wartime activities. The WSJ reported that Barofsky has already uncovered documents and testimonies suggesting that critical information was intentionally withheld during the 1990s probes.

Barofsky recently told the U.S. Senate that his team expects to issue a final report in early 2026. This report is anticipated to shed light on the extent of Credit Suisse’s wartime entanglements and provide a clearer understanding of whether previous investigations were actively obstructed from reaching the full truth.

As the WSJ report highlighted, the evidence uncovered so far includes registry cards, client files marked with “American blacklist” stamps, and internal communications suggesting that executives were aware of problematic accounts but chose not to disclose them.

“From the beginning, the Senate Budget Committee’s bipartisan goal was to ‘leave no stone unturned’ in pursuit of justice for those wronged by Nazi atrocities. Our investigation has dug up more than just stones – we’ve found boulders. Credit Suisse hid additional evidence of Nazi ties for years, and even tried to conceal information from our congressional investigation. While the 118th Congress may be over, the work to shine light on the darkest corners of Credit Suisse’s history continues. Ultimately, it’s my hope to see these records preserved in a repository that researchers can reference to discover untold stories and future generations will learn from,” Senator Grassley said.

“Throughout this investigation, this Committee has been driven by a commitment to truth and justice for all who were victimized by Credit Suisse’s historical servicing of Nazi accounts, including Holocaust survivors and their families,” Senator Whitehouse said earlier this week. “I share Ranking Member Grassley’s commitment to leaving no stone unturned when it comes to investigating Nazis and their enablers in the pursuit of transparency and accountability. Our inquiry has already exposed new details about Credit Suisse’s servicing of Nazi clients and their enablers and has prompted UBS to take additional action to ensure a thorough review of all relevant records.”

The implications of these findings go beyond financial restitution—they strike at the heart of institutional accountability and historical justice. As The Wall Street Journal report emphasized, the cover-up, whether intentional or the result of systemic negligence, deprived countless families of closure and resolution.

For Holocaust survivors and their descendants, the revelations represent a painful reopening of wounds. For historians and policymakers, they shine a proverbial spotlight on the ongoing need for transparency and independent oversight when dealing with historical injustices.

UBS, now the custodian of Credit Suisse’s legacy, has vowed to fully support Barofsky’s investigation. A UBS spokesperson told WSJ: “UBS is committed to contributing to a fulsome accounting of Nazi-linked legacy accounts previously held at predecessor banks of Credit Suisse.”

As Barofsky’s team continues its investigation, the WSJ reported has suggested that more discoveries could follow, potentially rewriting parts of the narrative Switzerland has told itself—and the world—about its wartime financial role. The final report, expected in 2026, may bring long-overdue clarity but also further fuel demands for accountability and potentially additional restitution.

As The Wall Street Journal correctly pointed out, the pursuit of truth in this matter is not just about uncovering financial records—it’s about honoring the memories of those who suffered and ensuring that such injustices are never buried or forgotten again.