|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Yehudis Litvak

Although the printing press—invented in Germany in the 15th century—met some opposition in the Christian world, it was received with much enthusiasm by the People of the Book.

Guild restrictions in Germany at the time did not allow Jews to own printing presses, but when two German printers moved to Subiaco, Italy, and began printing books in Latin, three Jewish brothers from nearby Rome took the opportunity to learn the art of printing.

The brothers, Obadiah, Manasseh, and Benjamin, soon began printing Hebrew books; among the first was Rabbi David Kimchi’s Sefer Hashorashim, a work on Hebrew grammar. Though the exact date is unknown, experts estimate that it was printed between 1469 and 1473.

The earliest dated printed Hebrew book is Rashi’s commentary on the Torah, printed in 1475 by Abraham ben Garton in Reggio di Calabria, Italy. Unlike the brothers from Rome who used the square print similar to the letters of the Torah scroll, Abraham ben Garton modeled his print after a Sephardic semi-cursive script. To this day, the font is known as the Rashi script.

Books produced at the dawn of the printing era (up until 1500) are called incunabula, which means “cradle books.” Hebrew incunabula were printed in 23 printing shops in Italy, Spain, and Portugal. In addition, Paris, Leiden, and Constantinople each had a Hebrew printing shop.

Though tens of thousands of Latin incunabula still exist, very few Hebrew ones survived centuries of persecution, expulsion, and censorship. Altogether, there are fewer than 200 editions of Hebrew incunabula in libraries and private collections all over the world, most just small fragments of the original books. Some of these rare and precious books and fragments can be found in the Library of Agudas Chasidei Chabad, which we shall discuss below.

Beginnings of Hebrew Printing in Spain

Solomon ben Moses ha‑Levi ibn Alkabetz, a scion of a prominent Sephardic family, operated a Hebrew printing press in the Spanish city of Guadalajara between 1476 and 1482, assisted by his sons, Joshua and Moses.

Though short-lived, the press printed hundreds of copies of the Hebrew books most in demand in Spain at the time: Rashi’s commentary on the Torah, prayer books, Passover Haggadah, Megillat Antiochus on the story of Chanukah, Rabbi David Kimchi’s commentary on the Prophets, Talmudic tractates, and others.

Researcher Joshua Bloch describes Alkabetz’s books:

The Hebrew books they produced, in a measure, reflect the degree of culture, the scope of interest and the material and intellectual activities of the time. The quality of paper, the frequent use of vellum, the shining luster of the ink, the style and ornamental designs of the letters and borders – all indicate a life of ease, comfort and even security.1

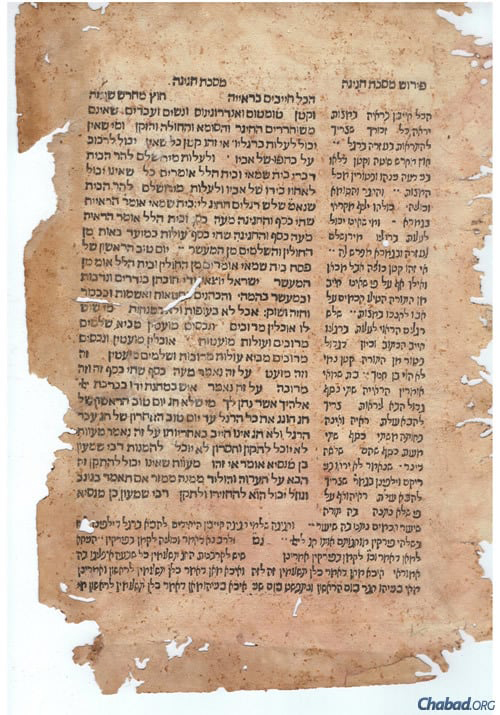

Most of those books no longer exist, likely due to the Inquisition’s Hebrew book burnings in 1491 and 1498. The Alkabetz family had to close their printing shop and leave Spain.2 Two surviving folios of the Talmud printed in this press can be found in the Chabad Library.

Printing Hebrew Books in Secret

One of the earliest Hebrew printers in Spain was a converso named Juan de Lucena. Though he had publicly converted to Christianity, he continued practicing Judaism in private. In 1476, he established two secret Hebrew printing shops, one in Toledo and another in the small village of Montalban. He printed the Torah, several tractates of the Talmud, and several books on Jewish law.3

When his activities fell under suspicion of the Inquisition in 1481, Juan and his sons fled to Portugal and later to Italy. His daughters did not manage to escape. Under interrogation by the Inquisition, Juan’s daughter Teresa admitted that Judaism was practiced in her father’s home and that she had assisted him with Hebrew printing. Teresa was sentenced to life imprisonment but was later released in exchange for a large sum of money.4

Only isolated fragments of Juan’s books have survived.

Another piece of the story of the hidden Jews can be inferred from a Yom Kippur prayerbook, currently located at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York:

This is a highly unusual book, first of all, because of its non-standard form, being shaped like an elongated rectangle, as if it were made on purpose to be hidden. In describing this unique production in his annual library report, A. Marx (1977, 65) remarked: “It can only be imagined that this peculiar size was selected so that it should be possible for a Marrano, when surprised during the prayers, to slip it into his sleeve or pocket.” The book has distinct beautiful prints and this shows that the printing house where it was issued must have been an experienced one. Unfortunately, we know nothing about that house, and its prints, although relatively standard, do not match any others that are familiar to us.5

Hebrew Printing in Portugal

Jews were expelled from Portugal five years after the expulsion from Spain, which meant Hebrew printing in Portugal lasted five years longer.

Among early Hebrew printers in Portugal was Eliezer Toledano, who printed his first book, Nachmanides’ commentary on the Torah, in 1489 in Lisbon. “Toledano’s editions are distinguished by their unique elegance and diversity of prints, their printing clarity and use of numerous decorative elements such as frames and headpieces,” writes Professor Iakerson.6

Another printer, Samuel Dortas—assisted by his three sons—printed Hebrew books in Leiria, Portugal, until shortly before the expulsion.

His was the first Jewish print shop to also print books in Latin characters. In 1496, they printed Abraham Zakuto’s astronomical tables in Latin and Spanish.7

The Soncino family

The most famous of the early Hebrew printers is the Soncino family of Soncino, Italy, who brought their Ashkenazic traditions with them when they emigrated from Germany. Like their Sephardic counterparts, they printed classic Jewish texts, but with a focus on commentaries authored by Ashkenazic rabbis, such as the Tosafot commentary on the Talmud.

In 1480, the family’s patriarch, Israel Nathan Soncino, a doctor by profession, instructed his son, Joshua Solomon, to open a printing press. Joshua Solomon began by printing the first tractate of the Talmud. Assisted by his nephew, Gershom, he continued to print additional tractates.8

The Soncinos used artistic borders and prints to enhance their books’ appearance. The decorative frames had originally been commissioned for and used by non-Jewish printers, who later sold them to Jewish printers.9

Joshua Solomon died from the plague in 1493. Gershom moved around Italy before moving to Salonika and later Constantinople. He continued printing wherever he lived, publishing close to one hundred titles over the course of his long career, though he did not manage to print the full set of the Talmud.

In a note in one of his books, Gershom wrote, “I toiled and found books that were previously closed and sealed, and brought them forth to the light of the sun, to shine as the firmament.”10 Indeed, he traveled extensively to obtain original manuscripts.

Hebrew Books Travel the World

A fascinating part of the story of early Hebrew printing is how far the books traveled. Some of the books printed in the Iberian Peninsula and Italy eventually made their way to Persia and Yemen, for example.11

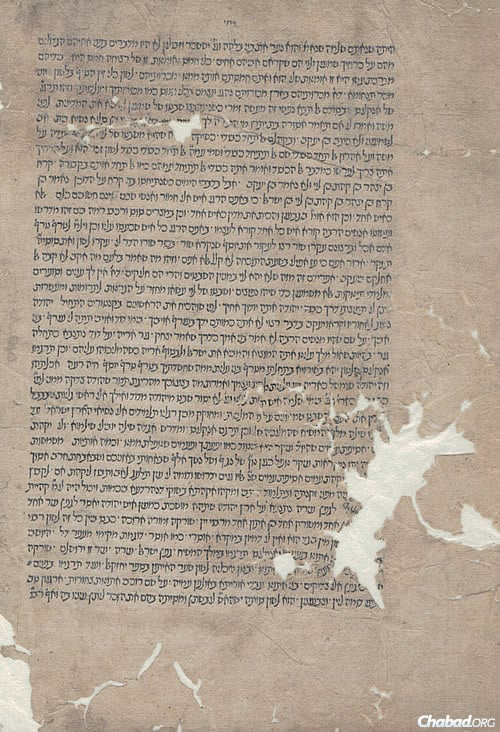

The National Library of Israel holds a copy of the Early Prophets, in 3 volumes, printed in Leiria, Portugal, in 1494. The books were donated to the library by Abraham Shalom Yahuda, a scholar and collector.

The first volume is inscribed:

Purchased with my money, I, Moses Alashkar, son of the Judge Isaac Alashkar, may my Rock and Redeemer keep me, and peace to Israel, amen.12

The note was an exciting find for researchers. Rabbi Moses Alashkar is a known figure—a prominent rabbi and judge in Spain who traveled to North Africa after the expulsion, eventually ending up in Egypt.

But the books’ journey didn’t end there. Two centuries later, they were sold and purchased in Yemen twice. The first deed of sale, recorded in the book, states:

Testimony record of my purchase. A man should always write his name on his book, lest a wicked person come from the market saying it was his. I, Joseph son of David al-Madai, bought this item [consisting of] three books – Book of Joshua and Book of Judges, and Book of Samuel, and Book of Kings – and Mishnah with [the commentary] Kaf Nachat for four and a quarter silver Kurush from Salam al-Gav’i. Amen, may it be His will … 13

The names mentioned in the deed belong to well-known Yemenite families. The date of the transaction is partially erased, but it is believed to have occurred either in 1729 or 1749.

The second deed of sale is less legible, but the date is clear – 1755.

Hebrew Incunabula Today

Besides the National Library of Israel, surviving Hebrew incunabula are located today in private collections, museums, and libraries all over the world.

In the United States, a significant collection is held in the Library of Agudas Chasidei Chabad, housed in the building adjacent to the Chabad Lubavitch World Headquarters, 770 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY.

Among its highlights are halachic texts like Mishneh Torah by Maimonides, with notable editions such as the 1550 version published by Bragadin in Venice; a portion of the 1475 edition of Rashi’s commentary on the Torah (only one full copy has survived until today), published in Reggio di Calabria; and a 1554 edition of Rabbi Yitzchak Alfasi’s legal code printed in Sabbioneta.

The collection also includes rare first editions of Kabbalistic masterpieces, such as Rabbi Yehudah Hayyat’s commentary on Ma’arekhet ha-Elokut, printed in 1558, and the first printed editions of the Zohar, published in Mantua and Cremona that same year.

Beyond legal and mystical works, there are fragments of medieval Torah scrolls, early printed Talmud folios—including the 1482 Guadalajara edition—and philosophical texts like Maimonides’ Guide for the Perplexed, published in 1555. The literary scope extends further, encompassing Hebrew grammar and lexicography, liturgical texts, and even satirical poetry, such as Mahbarot Immanuel, published in Constantinople in 1535.

Other treasures of the library include original manuscripts by the Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Kordovero) and most of Rabbi Chaim Vital’s transcripts of the teachings of his master, the Arizal, which eventually became known as Kitvei HaArizal.

In addition, the Library of Congress in Washington, DC,holds at least two dozen Hebrew incunabula in its Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Among them is a set of Prophets printed by Joshua Solomon Soncino in 1485-1486. In the first half of the 19th century, the set had belonged to Prince Augustus Frederick, the Duke of Sussex, the ninth child of King Charles II of England. After the duke’s death, his estate was sold and the set eventually made its way to John Boyd Thacher, New York State senator and rare book collector. Thatcher’s collection was bequeathed to the Library of Congress by his widow in 1927.14

Other significant collections of Hebrew incunabula are held at Det Kongelige Bibliotek in Copenhagen, Stadtund Universitaetsbibliothek in Frankfurt on the Main, Bodleian Library in Oxford, Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, Bibliotheca Friedlandiana in St. Petersburg, and Kultusgemeinde in Vienna.

Footnotes

- Quoted in Marvin J. Heller’s Guadalajara: A Fifteenth Century Hebrew Press of Distinction.

- They settled in Salonika. Joshua Alkabetz lived there for the rest of his life. Moses Alkabetz served as a rabbi in Adrianople, Salonika, and Aram Zoba, Syria. Moses’s son, named Solomon after his grandfather the printer, was the well known rabbi and kabbalist of Safed who authored the Friday night prayer Lecha Dodi.

- Norman Roth. Conversos, Inquisition, and the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain. University of Wisconsin Press, 2002. Pages 180-181.

- Shimon Iakerson. Early Hebrew Printing in Sepharad.

- Shimon Iakerson. Early Hebrew Printing in Sepharad.

- Shimon Iakerson. Early Hebrew Printing in Sepharad.

- Shimon Iakerson. Early Hebrew Printing in Sepharad.

- Marvin J. Heller. Earliest printings of the Talmud. Printing the Talmud: Essays.

- Marvin J. Heller. Earliest printings of the Talmud. Printing the Talmud: Essays.

- Quoted in Marvin J. Heller’s Earliest printings of the Talmud. Printing the Talmud: Essays.

- Alexander Gordin. Hebrew Incunabula in the National Library of Israel as a Source for Early Modern Book History in Europe and Beyond.

- Translated from Hebrew. Quoted in Alexander Gordin. Hebrew Incunabula in the National Library of Israel as a Source for Early Modern Book History in Europe and Beyond.

- Translated from Hebrew. Quoted in Alexander Gordin. Hebrew Incunabula in the National Library of Israel as a Source for Early Modern Book History in Europe and Beyond.

- Haim A. Gottschalk. A Survey of the Hebrew Incunabula at the Library of Congress.