|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Distinct from dizziness, vertigo is the sensation of movement or spinning despite nothing moving. It affects up to 10 percent of people at least once.

By: Mercura Wang

Vertigo is a form of dizziness in which a person feels like they are moving even though everything is still. People often feel like they, their surroundings, or both are spinning.

Dizziness is a broader term that, in addition to vertigo, includes lightheadedness (feeling woozy), disequilibrium (a sense of imbalance or instability), and presyncope (a feeling of impending faintness).

Overlap and confusion of these and other similar conditions make it difficult to provide accurate statistics on the number of people affected by vertigo. However, a rough estimate for adults in the general population is that at least one-quarter have dizziness, and about 7 percent to 10 percent experience vertigo at least once in their lives.

What Are the Types of Vertigo?

Vertigo can be classified into two types: peripheral and central.

- Peripheral

Peripheral vertigo arises from issues in the inner ear’s balance structures, such as the vestibular labyrinth or semicircular canals, or may involve the vestibular nerve connecting the inner ear to the brain stem. Peripheral vertigo often presents as acute, intense episodes that worsen with head movements. Up to 90 percent of vertigo cases are peripheral, while the rest are central.

- Central

Central vertigo is caused by an issue within the brain, typically in the brain stem or the cerebellum at the back of the brain. It poses a considerable challenge in health care because it can lead to serious consequences if not quickly recognized and treated.

The key difference between peripheral and central vertigo is that peripheral vertigo primarily involves the inner ear or vestibular nerve (vestibulocochlear symptoms). In contrast, central vertigo involves central nervous system dysfunction (including additional brain stem-related symptoms). Brainstem-related symptoms include slurred speech, trouble moving the eyes, and facial paralysis.

What Are the Symptoms of Vertigo?

Vertigo is a symptom rather than a condition in and of itself. It is a false sensation of movement, often described as spinning or whirling, that differs from dizziness.

Vertigo episodes may last from 30 seconds to several days, and some individuals may experience chronic dizziness for months or even years. While certain causes of vertigo may last less than a minute in a lab setting—usually around 20 to 40 seconds—people often report a lingering sensation of imbalance that can feel like it lasts much longer, sometimes perceived as lasting all day.

What Causes Vertigo?

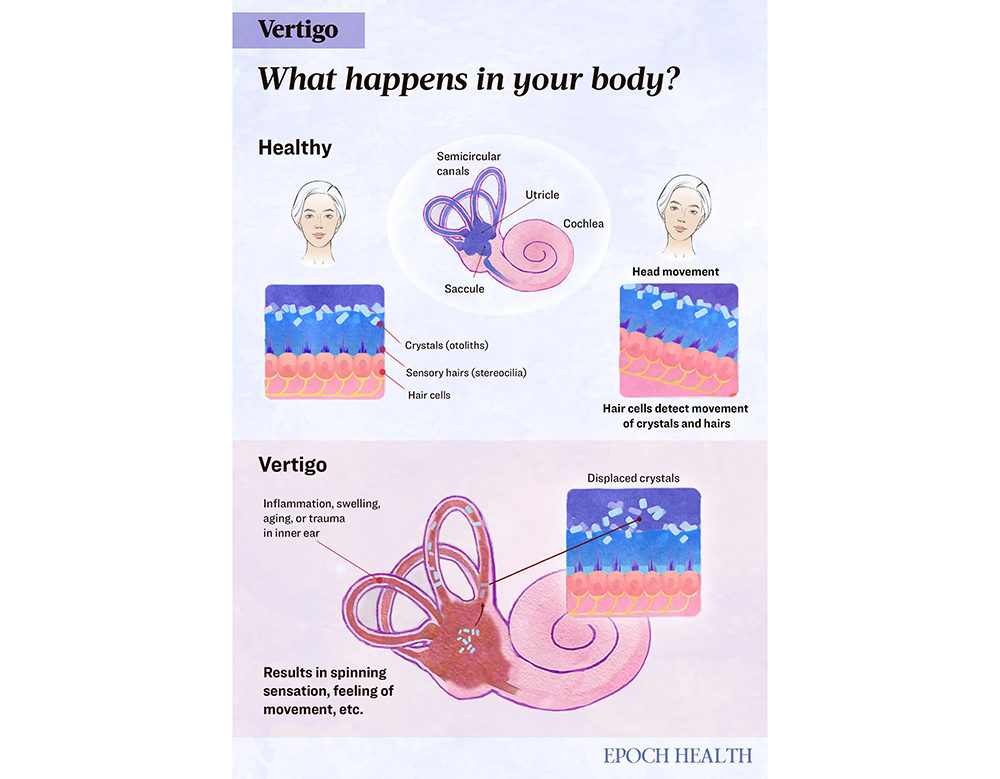

The inner ear has important structures that help people balance and understand their movements. These are the semicircular canals, utricle, and saccule, which are filled with liquid. When we move our heads, this liquid shifts and sends signals to our brains, informing us that we are moving. Once we stop moving, the liquid also stops.

The utricle and saccule help us sense movements like going up and down or side to side. They contain tiny calcium carbonate earstones, or crystals, called otoliths and hair cells that sense linear movements and gravity. Otoliths shift when we move our heads and push against tiny hairs, sending messages to our brains about our position.

Vertigo usually occurs when there’s a disruption in the inner ear’s balance system or the nerve that connects it to the brain. This disruption can come from damage to the related organs or mixed-up signals. The brain receives information from both sides of the inner ear. It combines it with visual and body sensory input to determine whether the person is moving or if the environment is. When there is asymmetry in the vestibular system, these signals don’t match, so they overwhelm the brain, causing dizziness, nausea, or the feeling of spinning or movement.

Although vertigo can affect people of all ages, the following factors put a person more at risk:

Sex: Vertigo occurs in women two to three times more often than in men.

Age: Older adults have a higher prevalence of vertigo, as it increases with age. Age-related changes in the inner ear also increase the likelihood of conditions such as vestibular disorders.

Certain occupations: Aircraft pilots and underwater divers often experience vertigo due to the lack of reference points in their environments, leading to disorientation.

Frequent travel: People who travel often, especially by air, may experience vertigo related to changes in pressure or motion sickness.

How Is Vertigo Diagnosed?

To diagnose vertigo, a health care provider reviews the patient’s medical history and symptoms. The patient’s history is crucial in diagnosing dizziness and, more specifically, narrowing it down further to vertigo (versus lightheadedness or other types of dizziness).

A health care provider then performs a physical exam to identify potential causes of vertigo. The following tests may be performed:

HINTS test: The head impulse test, nystagmus, and skew deviation (HINTS) test is the most effective bedside method to distinguish between peripheral and central vertigo. However, this test is only valid if the patient is still experiencing ongoing, continuous vertigo during the assessment.

Videonystagmography testing: Videonystagmography assesses inner ear function through a series of visual and sensory exercises. Since the inner ear sends signals to the eye muscles to help maintain balance, this test records eye movements to help audiologists determine if inner ear issues are causing vertigo.

The Dix-Hallpike test: The Dix-Hallpike maneuver is considered the “gold standard” test for diagnosing BPPV. During the test, the patient is seated on an exam table and asked to look at a fixed point (like the examiner’s nose). The patient’s head is turned to one side and lowered toward the table. If the patient experiences vertigo (“dizziness”) and has nystagmus, it indicates likely BPPV in the ear facing the floor. The process is then repeated on the other side to examine the opposite ear.

Rotational chair testing: The rotational chair test helps identify whether vertigo originates from peripheral or central causes. In this test, the patient sits in a rotating chair and wears special goggles that record eye movements, allowing the audiologist to assess how the balance system responds.

Other inner ear tests: Additional inner ear tests may include vestibular evoked myogenic potentials testing, which measures the response of the vestibular system and neck muscles to sounds, and electrocochleography, which checks for fluid buildup and pressure in the inner ear. Audiologists use these tests to assess how the inner ear responds to sound stimuli.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan: For some people with vertigo, especially those with hearing loss, doctors may recommend an MRI scan to closely examine the inner ear and nearby structures to detect fluid buildup, inflammation, or growths on the nerve that may be causing symptoms.

Neurological testing: If hearing or sensory tests suggest that vertigo is centrally caused, doctors may refer the patient to a specialist for neurological evaluation and treatment.

Computerized dynamic posturography (CDP): CDP is a specialized test used to assess an individual’s balance and postural control. It measures how well a person can maintain their balance under various conditions.

Other tests: Other tests recommended by the doctor may include blood tests, hearing tests, caloric stimulation (uses temperature differences to diagnose damage to the acoustic nerve while also checking for potential damage to the brainstem), lumbar puncture, and gait testing.

What Are Possible Complications of Vertigo?

Complications of vertigo may include:

Falls and injuries: Since vertigo can lead to loss of balance and disorientation, it can cause falls, which may result in hip fractures, head injuries, or other trauma.