|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Dion J. Pierre

“Dark money” is an accusation progressive journalists and pundits have lodged for years to elicit fears of old white men—conservative and perhaps connected to the fossil fuel industry—paying millions of dollars to impose their reactionary politics on an unsuspecting American public it continuously blocks from being on “the right side of history.”

The Koch Brothers come to mind. And these days, so does Harlan Crow, to his misfortune. “Dark money” also prompts concerns about the excesses of capitalism, of rapacious CEOs who value profits more than people, inveigle politicians into rigging their system in their favor, and would even sacrifice the health of the planet if doing so meant buying just one more yacht.

Progressivism, aiming to serve as the conscience of the American mind, has always appointed itself as our Cassandra, warning of the wrath to come should we ignore the consequences of allowing the immensely wealthy to wield disproportionate power over our democracy. “Corporations are not people,” the activists clamored. “Money isn’t speech.”

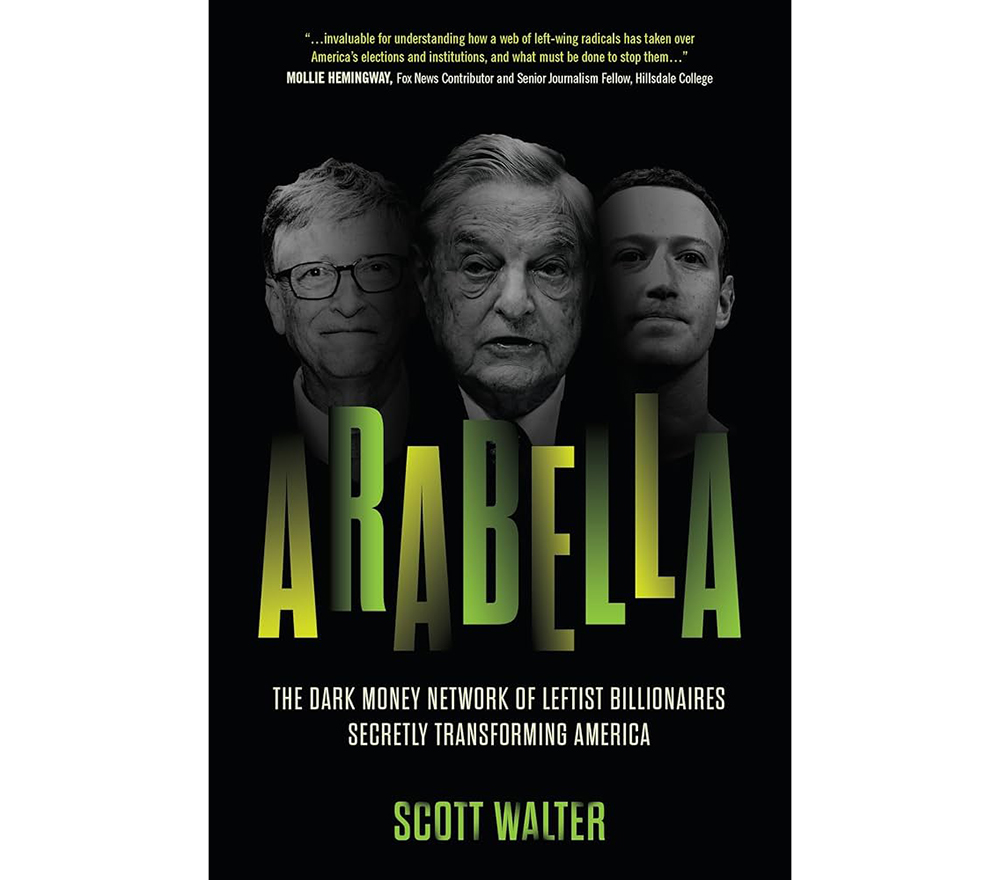

For these reasons, it may come as a surprise to readers of Capital Research Center president Scott Walter’s new book, Arabella: The Dark Money Network of Leftist Billionaires Secretly Transforming America, that left-wing billionaires have gotten in on the dark money game to the tune of obscene sums of money. Not millions of dollars, but billions, he reports, more than both major national parties raised in last year’s election cycle combined.

The story he tells, centered around the machinations of the little-known consulting organization Arabella, LLC, is the stuff of spy novels, featuring front groups that pop up seemingly overnight to promote the next left-wing cause or smear the next right-wing star, efforts to influence national elections, and mass production of propaganda.

“This book is a sobering wake-up call to Americans, few of whom know about Arabella or its multibillion-dollar operation that is so deeply involved in their lives and their elections,” Walter writes. “Arabella’s successes reveal the Left’s stunning advantage in money and sophisticated political machinery.”

From bankrolling social media campaigns to thwarting nominations of conservative judges to electioneering and initiatives targeting off-road motorists in Montana, Arabella—funding a network of nonprofit organizations that funnels money from its billionaire benefactors into lobbying and activism—is everything progressives want “systemic racism” to be: pervasive and undetectable until one is awakened to its presence.

What Walter reveals is that progressives are doing what they accuse their enemies of: subverting democracy to the benefit of the few. A legal mafia, it leverages the rules that protect nonprofits from revealing their supporters to strong-arm the little guy and keep politicians in line. Its friends are major players in American philanthropy, legacy foundations such as the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, and left-wing heroes such as Warren Buffet and Bill Gates. Behind it all is Eric Kessler, a radical environmentalist whose family sold its auto parts manufacturing company for $750 million in the 1990s.

The scale of its efforts is profound, the figures staggering: $119 million here, $86 million there, and as pocket change, $1.5 million somewhere else. It is, Walter continues, a scandal barely reported on by our socially conscious media (as opposed to the Washington Free Beacon). These outlets are most comfortable taking the high ground when the people doing the sinning aren’t on their side. This is because the money supports their goals. Unlike the Koch Brothers, Scott explains, who dissed the “new-right” to oppose Donald Trump and have even partnered with George Soros, Arabella has exclusively reserved its liberality for the progressive movement. Conservatives need not submit a grant application.

Throughout reading the book, one is reminded that so much of what seems glamorous, respectable, and “current” about the progressive movement is merely a veneer. It is politics as it always has been: Who could blanch at learning ex-presidents sometimes pay a little hush money to protect their reputations after realizing the most clamorous vilifiers of such conduct use exponentially larger amounts money as a tool for getting everything they want?

Fifty years ago, Mario Procaccino, a Democratic mayoral candidate in New York City, coined the phrase “limousine liberal” to describe rich socialites who paid lip service to the politics of working people to draw attention away from their privilege. It was comical, making the person who embodied it an object of derision, like the Manhattanites who flooded Leonard Bernstein’s apartment in 1966 to hear the Black Panthers not so subtly tell them that they (and their children) might be casualties of the revolution, an account of which can be found in the late Tom Wolfe’s classic, Radical Chic and the Mau-Mauing Flak Catchers.

Today, the moniker is serious, and for some, it is perhaps a badge of honor. As Walter outlines, big money and big philanthropy have never been so aligned with the politics of the radical left. And the relationship has been successful, resetting the parameters of debate and inching the country closer to a reality we could not have conceived just 10 years ago.

There is cause, however, to hope that Arabella’s vision for America will be rejected by the very people it wants most to claim as allies, Walter says.

“The left faces a major problem: Where its ideas became entrenched—from big cities like San Francisco to prestigious colleges—they produce ugly realities that become a hindrance to the left’s utopian dreams of control. Those dreams, when brought into real life, become nightmares,” he concludes. “Most Americans don’t hold left-wing views on so many issues, from crime to race relations to voter ID laws. In fact, as I write, the black mayor of Dallas, a longtime Democrat, has switched parties.”

Arabella: The Dark Money Network of Leftist Billionaires Secretly Transforming America

by Scott Walter

Encounter Books, 248 pp., $50

Dion J. Pierre is the campus correspondent for the Algemeiner. He was previously a research associate at the National Association of Scholars, where he wrote “Neo-Segregation at Yale.”