By: Dr. Yvette Alt Miller

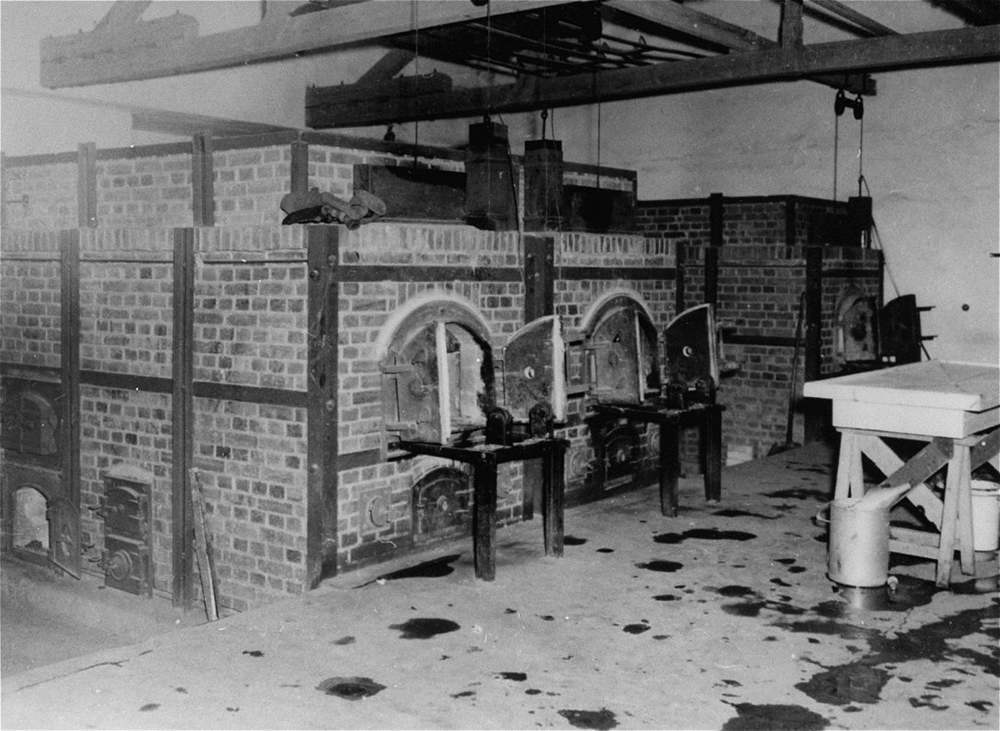

As World War II drew to a close in 1945, survivors of the Nazi death camps tried to rebuild their shattered lives in Displaced Person (DP) camps, many of which were housed in the very concentration camps in which Nazis had recently tortured and murdered Jews and others.

On September 29, over three months after the end of the war in Europe, US President Harry S. Truman wrote a scathing letter to Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was in charge of American troops in occupied Germany, describing the horrific conditions that Jews were still living in. Pres. Truman quoted from a report on the conditions in the DP camps that he’d commissioned: “As matters now stand, we appear to be treating the Jews as the Nazis treated them except that we do not exterminate them. They are in concentration camps in large numbers under our military guard instead of S.S. troops. One is led to wonder whether the German people, seeing this, are not supposing that we are following or at least condoning Nazi policy.”

Truman argued that “we have a particular responsibility toward these victims of persecution and tyranny who are in our zone. We must make clear to the German people that we thoroughly abhor the Nazi policies of hatred and persecution. We have no better opportunity to demonstrate this than by the manner in which we ourselves actually treat the survivors remaining in Germany.”

With American support, Jewish life slowly began to return to the camps. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee moved into many DP camps and helped distribute food and medical supplies. They also helped set up Jewish schools in the camps, aided at times by the American army and also by some remarkable rabbis who’d survived the Holocaust and were determined now to rebuild Jewish life.

One huge problem prevented the resumption of Jewish education and religious services: while the Nazis murdered as many Jews as possible and tried to wipe out Jewish existence, they also destroyed countless Jewish books, Torah scrolls and other ritual objects. Allied officials were able to find some Jewish prayer books in Nazi warehouses, but the ragged Jewish survivors in DP camps still lacked many basic Jewish books and supplies.

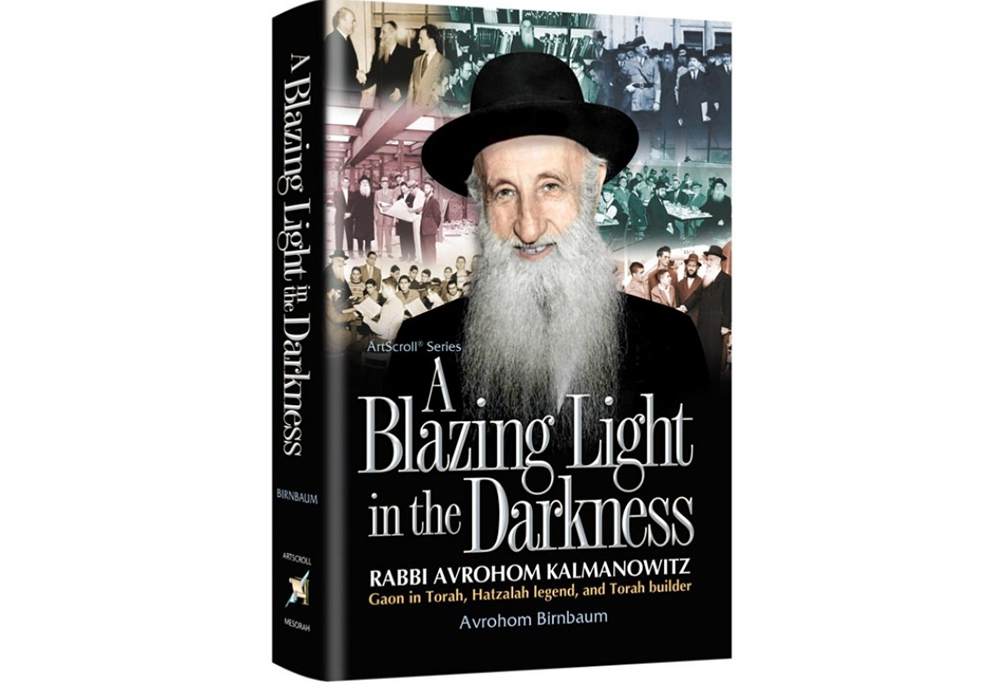

One leader who stepped in to help was Rabbi Avrohom Kalmanowitz. Born in Russia, Rabbi Kalmanowitz was head of the renowned Mir Yeshiva, one of the greatest yeshivas in the world. In 1939, with war looming, Rabbi Kalmanowitz decided to relocate his famous school from Lithuania to Kobe, in Japan. He set out to bring 575 members of the school, but soon found himself leading nearly 3,000 Jews who were desperate to escape Nazi Europe. He led this group, which included many sick and elderly Jews, across Russia and Siberia and onto Japan. For much of the journey, stronger members of the group would carry those who couldn’t walk on their backs.

After Japan attacked the United States, Rabbi Kalmanowitz moved his yeshiva once more, to Shanghai. There he improvised printing presses using stones and managed to publish 38,000 Jewish books. “While Hitler was burning books and bodies,” Rabbi Kalmanowitz later recalled, “the men of Mirrer (the Mir Yeshiva) who had traveled 16,000 miles from Lithuania to Shanghai were using stones for printing presses to keep the light of learning alive.” After the end of the war, Rabbi Kalmanowitz returned to Europe, and once more championed the printing of Jewish books and preservation of Jewish life.

Rabbi Kalmanowitz was a leading figure in the Agudat Harabbanim and the Vaad Hatzalah. He cultivated contacts with American military officials and oversaw the printing of Jewish prayer books, Passover Haggadahs, copies of the Megillah of Esther for Purim, and even some volumes of the Talmud. “Rabbi Kalmanowitz is a patient and appreciative old patriarch,” Gen. John Hilldring, the US Assistant Secretary of State for Occupied Areas, wrote to a colleague. “I can think of no assistance I gave anyone in Washington…that gave me more satisfaction than the very little help I gave the old rabbi.” Rabbi Kalmanowitz requested resources to print even more Jewish books but was told that with the acute shortage of paper in Germany, more ambitious plans to print Jewish books was impossible.

Seeing Rabbi Kalmanowitz’s success in printing some Jewish books and even some volumes of the Talmud, another Jewish leader in Europe at the time began to dream of an even more ambitious project. The chief rabbi of the US Zone in Europe was Rabbi Samuel Abba Snieg. He was a commanding figure. Before he was captured by the Nazis he was a chaplain in the Lithuanian army. He was sent to the Jewish Ghetto in Slabodka, a town near Kovno in Lithuania which was renowned as a center of Jewish intellectual life. From there, Rabbi Snieg was sent to the notorious Dachau concentration camp. He survived, and after being liberated dedicated his life to rebuilding Jewish life. He was assisted by Rabbi Samuel Jakob Rose, a young man who’d studied at the famous Slabodka Yeshiva before the Holocaust. They resolved to approach the US military for help in printing copies of the Talmud – the first volumes of the Talmud to be printed in Europe since the Holocaust.

A set of Talmud – called “Shas” – is made up of 63 tractates, comprising 2711 double-sided pages. For millennia, its many volumes have been studied day and night by Jews around the world. Printing a complete set of the Talmud would send a powerful message that Jewish life was possible once again.

Whom to ask for help? General Joseph McNarney was the commander of American forces in Europe. The rabbis wondered if there might be a way to reach him with their request, and decided to approach his advisor for Jewish affairs, an American Reform rabbi from New York named Philip S. Bernstein.

Rabbi Bernstein came from a very different background from the black-hatted Orthodox rabbis laboring in the DP camps. On the surface, perhaps, the men looked very different. But Rabbi Bernstein’s mother had come from Lithuania and he had a deep attachment to Jewish life and was open to requests for help in rebuilding Jewish education in the DP camps. Rabbi Snieg and Rabbi Rose explained their proposal to print whole sets of the Talmud on German soil, and Rabbi Bernstein became an enthusiastic supporter of the plan.

They arranged a meeting with Gen. McNarney in Frankfurt where they asked if the US army would lend “the tools for the perpetuation of religion, for the students who crave these texts…” Gen McNarney realized that printing sets of the Talmud would be a powerful symbol of the triumph of Jewish life – supported by American forces – in the lands where it had so nearly been wiped out. On September 11, 1946, he signed an agreement with the American Joint Distribution Committee and Rabbinical Council of the US Zone in Germany to print fifty copies of the Talmud, packaged into 16 volume sets. It would be the first time in history that an army agreed to print copies of this core Jewish text. The project became known as the Survivors’ Talmud.

The team immediately ran into obstacles. First, it was impossible to find a set of Shas (the entire Talmud) anywhere in the US Zone of former Nazi lands. “Every Jew in Poland was ordered, upon pain of death, to carry to the Nazi bonfires and personally consign to the flames his copy of the Talmud,” one testimony recorded. In the end, a member of the American Joint Distribution Committee brought two complete sets of the Talmud from New York.

Even though the US Army had agreed to print the volumes, some officials objected to the expense. The timeframe and scope of the project kept changing. Then there was the sheer labor involved in printing what eventually became nineteen-volume sets of the Talmud: each copy needed 1,800 zinc plates which had to be painstakingly set and proofread. The project began in 1947 and was finally completed in late 1950. “…we are Gott sie Dank (Thank God) packing the Talmud” an American Joint Distribution Committee employee wrote in November, when they began distributing the Talmud. The Joint paid for additional sets of the Talmud to be printed; in the end, about 3,000 volumes were made. These were then shipped all over the world wherever Holocaust survivors from the the DP camps were settling. The Survivor’s Talmud made its way to New York, Antwerp, Paris, Algeria, Italy, Hungary, Morocco, Tunisia, South Africa, Greece, Yugoslavia, Norway, Sweden, and Israel.

From the outside, these sets of the Survivors’ Talmud looked like any other set of Shas. Their special origin is only visible on the title page, which shows a picture of the Land of Israel as well as a concentration camp surrounded by a barbed wire fence, with the words “From bondage to freedom, from darkness to a great light.” Below is this touching dedication:

“This edition of the Talmud is dedicated to the United States Army. The Army played a major role in the rescue of the Jewish people from total annihilation, and their defeat of Hitler bore the major burden of sustaining the DPs of the Jewish faith. This special edition of the Talmud, published in the very land where, but a short time ago, everything Jewish and of Jewish inspiration was anathema, will remain a symbol of the indestructibility of the Torah. The Jewish DPs will never forget the generous impulses and the unprecedented humanitarianism of the American Forces, to whom they owe so much.”

Some individual owners of this remarkable set of Talmud wrote their own dedications as well. One rabbi of a small town in Israel near Jerusalem recalled how he lost his wife and children when they were murdered in the Holocaust. Living in Israel, he spent his days studying from his Survivors’ Talmud. On the first page he hand-wrote his own dedication as well, which surely was the hope of many other survivors who studied this remarkable Survivors’ Talmud as well:

“May it be Thy will that I be privileged to dwell quietly in the land; to study the holy Torah amid contentment of mind, peace, and security for the rest of my days; that I may learn, teach, heed, do and fulfill in love all the words of Thy Love. May I yet be remembered for salvation for the sake of my parents who sanctified Thy name when living and when led to their martyr’s eath. May their blood be avenged! May I merit to witness soon the final redemption of Israel. Amen.”

This was the prayer of so many of the Jews who helped print and then studied the Survivor’s Talmud. This remarkable undertaking was a way of declaring that no matter how terrible circumstances became, Jews would always find a way to return to the Jewish texts that have always sustained us.