The decoding of DNA extracted from fragments of parchment of the Second Temple era Dead Sea Scrolls indicates that 2,000 years ago, Jewish society was open to parallel circulation of diverse versions of scriptural books.

The findings support the notion that for contemporaries, the most important aspects of the scriptural text were its content and meaning, not its precise wording and orthography.

An interdisciplinary team from Tel Aviv University, led by Prof. Oded Rechavi of TAU’s Faculty of Life Sciences, Prof. Noam Mizrahi of TAU’s Department of Biblical Studies, in collaboration with Prof. Mattias Jakobsson of Uppsala University in Sweden, the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) Pnina Shor and Beatriz and others has successfully decoded ancient DNA extracted from the animal skins on which the Dead Sea Scrolls were written.

By characterizing the genetic relationships between different scrolls fragments, the researchers were able to discern important historical connections.

The research, conducted over seven years, sheds new light on the Dead Sea Scrolls.

“There are many scrolls fragments that we don’t know how to connect, and if we connect wrong pieces together it can change dramatically the interpretation of any scroll,” Rechavi explained. “Assuming that fragments that are made from the same sheep belong to the same scroll, it is like piecing together parts of a puzzle.”

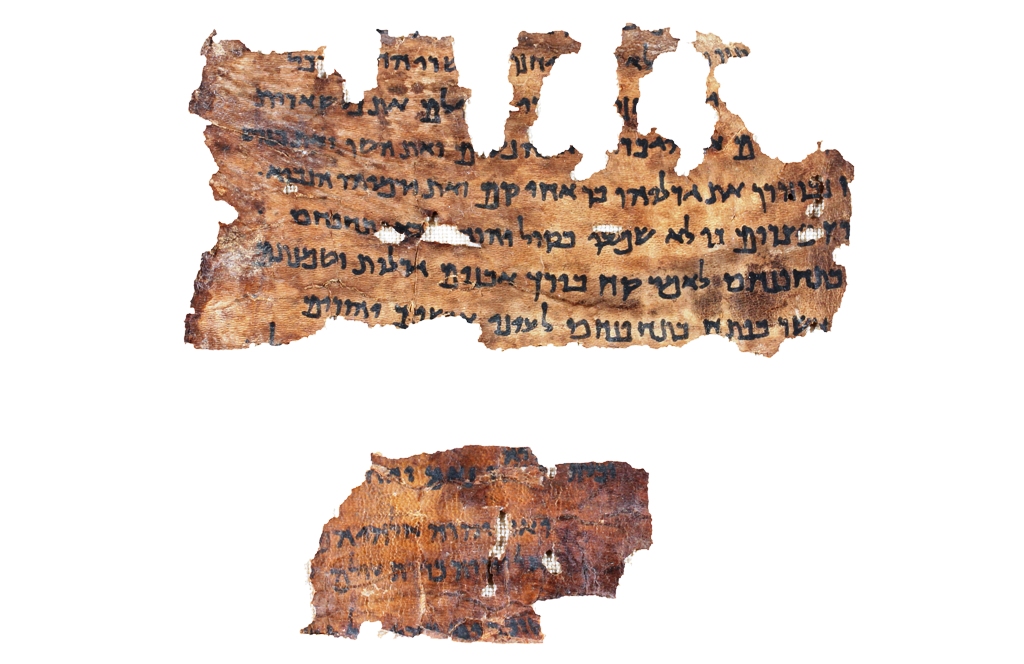

The Dead Sea Scrolls refers to some 25,000 fragments of leather and papyrus discovered as early as 1947, mostly in the Qumran caves but also in other sites located in the Judean Desert.

The Scrolls contain the oldest copies of biblical texts. Since their discovery, scholars have faced the significant challenge of classifying the fragments and piecing them together into the remains of some 1,000 manuscripts, which were hidden in the caves before the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE.

Today, the thousands of Dead Sea Scrolls fragments are preserved by the IAA, where their condition is monitored by advanced scientific methods, in a designated climate-controlled environment.

Researchers have long been puzzled as to the degree this collection of manuscripts, a veritable library from the Qumran caves, reflects the broad cultural milieu of Second Temple Judaism, or whether it should be regarded as the work of a fringe sect, identified by most as the Essenes, discovered by chance.

“Imagine that Israel is destroyed to the ground, and only one library survives – the library of an isolated, ‘extremist’ sect: What could we deduce, if anything, from this library about greater Israel?” Rechavi says. “To distinguish between scrolls particular to this sect and other scrolls reflecting a more widespread distribution, we sequenced ancient DNA extracted from the animal-skins on which some of the manuscripts were inscribed. But sequencing, decoding and comparing 2,000-year old genomes is very challenging, especially since the manuscripts are extremely fragmented and only minimal samples could be obtained.”

To tackle their daunting task, the researchers developed sophisticated methods to deduce information from tiny amounts of ancient DNA, used different controls to validate the findings, and carefully filtered out potential contaminations.

The team employed these mechanisms to deal with the challenge posed by the fact that genomes of individual animals of the same species, for instance, two sheep of the same herd, are almost identical to one another, and even genomes of different species such as sheep and goats are very similar.

The Dead Sea Scrolls Unit supplied samples, sometimes only scroll “dust” carefully removed from the uninscribed back of the fragments and sent them for analysis to the paleogenomics lab in Uppsala, which is equipped with cutting-edge equipment.

To orthogonally validate the work on the animals’ ancient DNA, a lab in New York studied the scrolls’ microbial contaminants.

Textual Pluralism Opens Window into Second Temple Culture

Rechavi noted that one of the most significant findings was the identification of two very distinct Jeremiah fragments.

“Almost all the scrolls we sampled were found to be made of sheepskin, and accordingly, most of the effort was invested in the very challenging task of trying to piece together fragments made from the skin of particular sheep, and to separate these from fragments written on skins of different sheep that also share an almost identical genome,” he said.

“However, two samples were discovered to be made of cowhide, and these happen to belong to two different fragments taken from the Book of Jeremiah. In the past, one of the cow skin-made fragments were thought to belong to the same scroll as another fragment that we found to be made of sheepskin. The mismatch now officially disproves this theory,” he elaborated.

“What’s more: cow husbandry requires grass and water, so it is very likely that cowhide was not processed in the desert but was brought to the Qumran caves from another place. This finding bears crucial significance, because the cowhide fragments came from two different copies of the Book of Jeremiah, reflecting different versions of the book, which stray from the biblical text as we know it today.”

“Since late antiquity, there has been almost complete uniformity of the biblical text. A Torah scroll in a synagogue in Kiev would be virtually identical to one in Sydney, down to the letter. By contrast, in Qumran, we find in the very same cave different versions of the same book. But, in each case, one must ask: is the textual ‘pluriformity,’ as we call it, yet another peculiar characteristic of the sectarian group whose writings were found in the Qumran caves? Or does it reflect a broader feature, shared by the rest of Jewish society of the period? The ancient DNA proves that two copies of Jeremiah, textually different from each other, were brought from outside the Judean Desert. This fact suggests that the concept of scriptural authority – emanating from the perception of biblical texts as a record of the Divine Word – was different in this period from that which dominated after the destruction of the Second Temple,” he said.

“In the formative age of classical Judaism and nascent Christianity, the polemic between Jewish sects and movements was focused on the ‘correct’ interpretation of the text, not its wording or exact linguistic form,” he added.

Findings Suggest Prominence of Ancient Jewish Mysticism

Another surprising finding relates to a non-biblical text, unknown to the world before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, a liturgical composition known as the Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice that was found in multiple copies in the Qumran caves and in Masada.

There is a surprising similarity between this work and the literature of ancient Jewish mystics of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Both Songs and the mystical literature greatly expand on the visionary experience of the divine chariot-throne, developing the vision of the biblical prophet Ezekiel. But the Songs predates the later Jewish mystical literature by several centuries, and scholars have long debated whether the authors of the mystical literature were familiar with Songs.

“The Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice were probably a ‘best-seller’ in terms of the ancient world: The Dead Sea Scrolls contain 10 copies, which is more than the number of copies of some of the biblical books that were discovered. But again, one has to ask: Was the composition known only to the sectarian group whose writings were found in the Qumran caves, or was it well known outside those caves? Even after the Masada fragment was discovered, some scholars argued that it originated with refugees who fled to Masada from Qumran, carrying with them one of their Scrolls,” Rechavi said.

However, “the genetic analysis proves that the Masada fragment was written on the skin of different sheep ‘haplogroup’ than those used for scroll-making found in the Qumran caves. The most reasonable interpretation of this fact is that the Masada Scroll did not originate in the Qumran caves but was brought from another place. As such, it corroborates the possibility that the mystical tradition underlying the Songs continued to be transmitted in hidden channels even after the destruction of the Second Temple and through the Middle Ages,” he offered.(TPS)