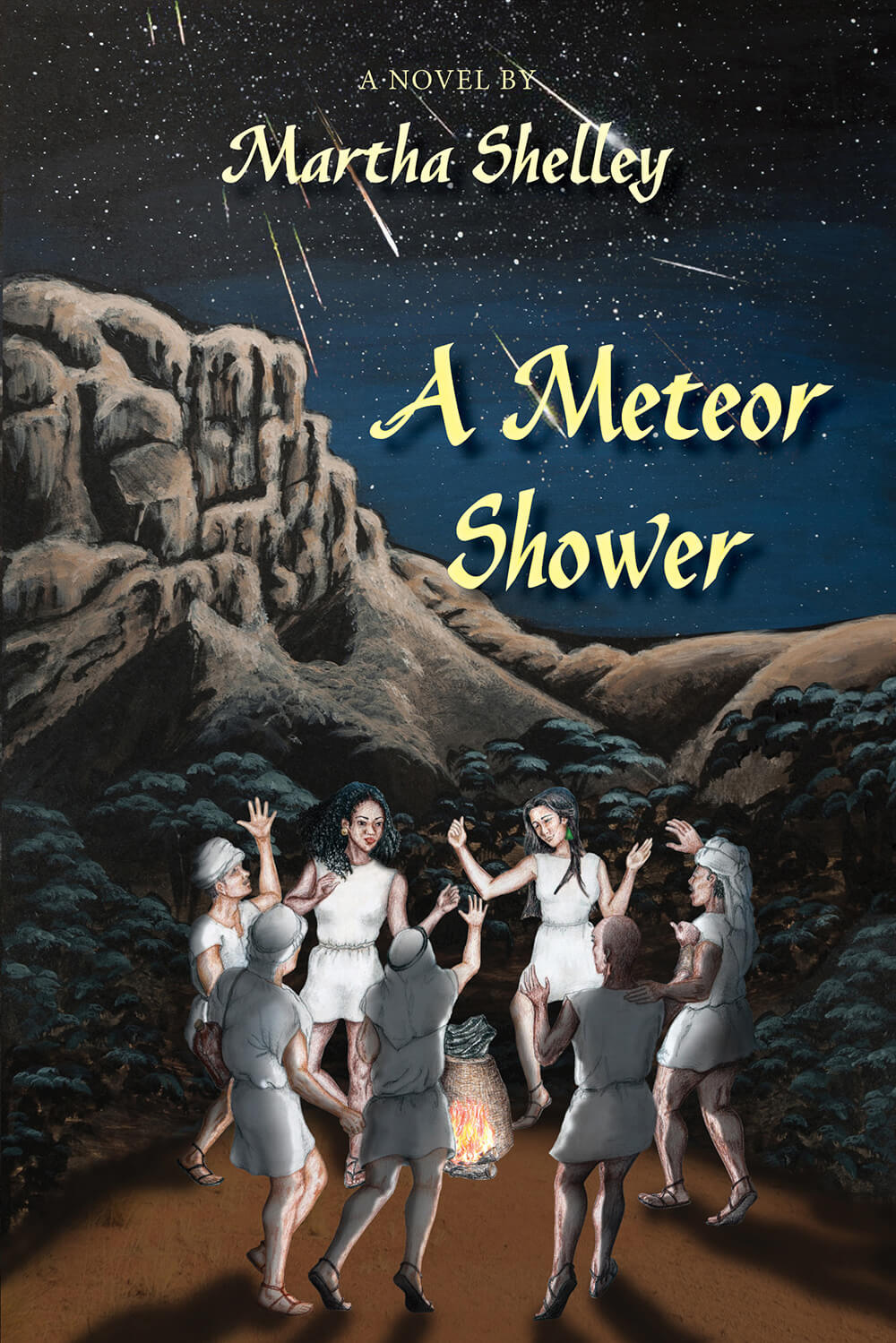

Review of Martha Shelley’s ‘A Meteor Shower’

By: Sylvia Allen

What did they do, the women of ancient Israel and its neighbors? Fewer than 8% of the named individuals in the Tanakh are women. Named or unnamed, most are presented as wives, daughters, sisters, concubines, or harlots—that is, defined by their relationships to men. Here, in a remarkable trilogy of historical novels, Martha Shelley retells the Elijah story, focusing on the lives and labors of women. These books follow Kings II but with a different take. They are unique in the world of Biblical fiction.

The overwhelming majority of people in the pre-industrial world simply tended their farms and flocks. That being said, in a stratified society such as the Iron Age monarchy, women would also have toiled at a variety of specialized occupations. Shelley’s heroines are among those.

A quick synopsis of the trilogy:

The first book, The Throne in the Heart of the Sea, takes us from the characters’ childhoods to Jezebel’s marriage to King Ahab. Tamar, the daughter of an Israelite fisherman, learns herbal medicine from her grandmother and writing from a refugee of the Assyrian wars. She is chosen as Jezebel’s personal scribe during the rise of the Tyrian empire, when such upward mobility was possible. Accompanied by Bez, a harem guard, she travels to Assyria and then to Egypt to study medicine. In the Tanakh we meet Elijah fully grown. Here he is a violently angry adolescent whose father was killed in the civil war, and whose inheritance was stolen.

The Stars in Their Courses opens in Egypt. While Tamar attends medical school, Bez discovers her own artistic talent and learns to paint murals. They return to Israel, where Tamar becomes a royal physician and Bez obtains commissions from wealthy patrons. Jezebel struggles to conceive and to retain her sense of herself in a life dominated by Ahab. Elijah has matured into his prophetic calling. After an Aramaean invasion, he organizes his disciples to rebuild ruined towns. This second novel culminates in 853 BCE, when a coalition of small kingdoms repels the mighty Assyrian empire. All our major characters go to war or, in Jezebel’s case, rule the kingdom while Ahab leads the troops.

A Meteor Shower, the final volume, takes us through the deaths of Ahab and Elijah, and Jehu’s massacre of the entire House of Omri. It also adds two significant female characters: Munapirtu, a pastry chef, who makes a living selling her wares in the public market, and Arneb, Tamar’s adopted daughter, who marries the boy next door and chooses the farming life. I won’t reveal the climactic ending, only to say that I stayed up until early morning to finish this book.

Underlying the drama is an extraordinary amount of research. Shelley introduces us to an array of cultures: agricultural Israelites and Aramaeans, sea-going Tyrians, Egyptians of various classes, nomadic desert people, and warlike Assyrians. We taste their foods, and smell the figs, the sheep dung, and the ripening wheat. We look over Tamar’s shoulder as she performs surgeries; we ride chariots to war. Here’s a passage from Ahab’s last battle, as seen by Caleb, his driver:

Caleb turned the vehicle around, no easy task in the thick of battle, and headed for the encampment where the medical team waited… “Lie down!” the driver bawled, almost in agony himself. “For the love of Yahweh, lie down!”

“No.” Ahab coughed. “That way.” He pointed toward the rise.

“But the doctor is—”

“No! They have to…see me …”

Caleb understood, and it hit him like a blow to the midsection. He almost stopped breathing.

…

When they reached the top of the rise, Caleb and the officers propped Ahab up, looping a rope several times around his chest and tying him to the rim of the chariot. They broke a spear in half, put it down the back of his shirt, and lashed it to his helmet, to keep his head erect. “Thank you,” Ahab whispered.

Caleb’s eyes blurred. My master. You’re going to sacrifice yourself to protect the rest of us. He thumped an officer’s arm. “Get a medic!”

It seemed like forever but was probably only a few moments before the officer returned with a medic riding double behind him.

“How do you expect me to work on him like that?” the doctor snapped. “Untie him. He’s got to lie flat.”

Ahab shook his head. His lips formed the word no, soundlessly. The doctor climbed into the chariot and ordered the others to hold Ahab’s arms and legs still while he tried to remove the arrow. The rivulet of blood became a steady stream. “Nothing I can do,” he said. “It’s in the liver.”

The battle raged on. Caleb tried to stanch the king’s wound. Refused to admit it was useless. Swallowed phlegm and tears. Now and then he looked up but couldn’t tell which side had the ascendant. Eventually the sun slid down and both armies drew back to their respective camps. And Ahab died.

The three books contain maps, a calendar, a glossary, and brief end notes on the author’s research. The last volume also has a family tree. I would have added a table of contents, which would have avoided my puzzling over the occasional foreign word before discovering the glossary in the back.

Shelley’s characters, even the minor ones, are well developed—no cardboard heroines or villains. I feared for Bez’s safety when she was taken captive, and wept at the death of Elijah. All of them are still with me even after turning the last page.

The books are available at www.ebisupublications.com. They are $15 each, with a $5 discount if you purchase the set.