|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Yaakov Katz

Assistant Secretary of State Barbara Leaf visited Damascus two weeks ago, leading a senior American delegation—the first to set foot in Syria since the civil war broke out in 2011. During her visit, the diplomat met with Syria’s new leader, Ahmed Hussein al-Sharaa, formerly known by his nom de guerre, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani.

Soon after, the U.S. dropped the $10 million bounty it had placed on al-Sharaa’s head in 2013, when he was designated a “Specially Designated Global Terrorist” due to his ties with al-Qaeda and his leadership of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS).

Only days later, French Foreign Minister Jean-Noel Barrot and German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock became the highest-ranking Western officials to visit Syria since the fall of Bashar al-Assad‘s regime last month.

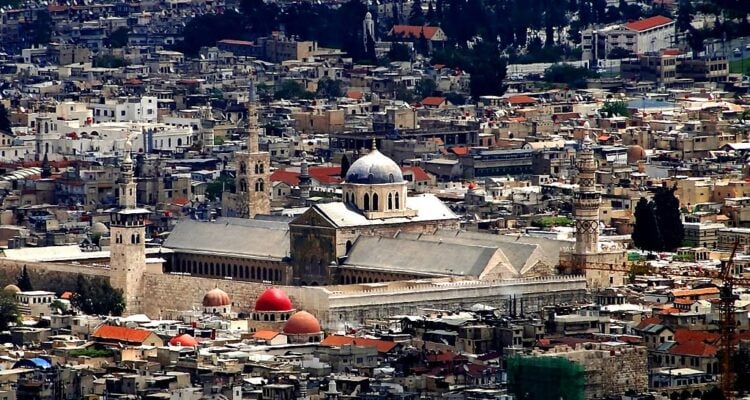

As al-Sharaa entertains foreign dignitaries in Damascus, his foreign minister, Asaad al-Shaibani, has been making the rounds through the Arab world. Recent stops included Amman—where he met with Jordan’s Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi—as well as visits to Qatar and Abu Dhabi.

Meanwhile, Maher Marwan, the new governor of Damascus, gave an interview to National Public Radio where he explained that Syria’s new leadership does not seek a conflict with Israel. “We have no fear towards Israel,” Marwan said. “Our problem is not with Israel. We don’t want to meddle in anything that threatens Israel’s security or that of any other country.”

For Israel, this evolving situation presents a serious dilemma. On the one hand, Jerusalem remains deeply suspicious of the new government in Syria. Just one month ago, al-Sharaa was labeled a terrorist by the U.S., and Syria was still serving as a main conduit of advanced weaponry to Hezbollah in Lebanon. Iran had established forward bases in Syria, not far from Israel’s border, and built a massive underground rocket production facility in the west. That facility was destroyed by the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) in a covert operation last September.

“Around the world, they speak of ‘organized regime change in Syria,’ but it’s not like a new government was chosen democratically and now controls all of Syria,” Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Saar remarked at the end of December. “This is a gang of terrorists who took Idlib, then captured Damascus and other areas.”

This stance reflects the prevailing Israeli view, but it’s becoming increasingly complicated. Pressure is mounting on Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu‘s government to withdraw Israeli military forces from the buffer zone, a strategic area Israel occupied after Assad’s forces were overrun and HTS took control of Syria. Israel has justified its presence there, arguing it is necessary to protect Israeli communities in the Golan Heights, an area seized from Syria in 1967, which is home now to about 50,000 Israelis.

But if al-Sharaa continues to present himself as a moderate, and even makes overtures toward Israel, the pressure on Netanyahu to pull back will intensify. Al-Sharaa has pledged to respect the 1974 ceasefire agreement with Israel, allow United Nations peacekeepers to return to the border, and prevent foreign forces like Iran from using Syrian soil as a launching pad for attacks on Israel.

The central question for Israel is whether the new Syrian government will open talks about the border and the future of the Golan Heights. Three previous Israeli governments, including one led by Netanyahu, held talks with Syria over the Golan. While President-elect Donald Trump recognized Israeli sovereignty over the Golan in his first term, the issue could resurface as a point of tension in the years ahead.

Israel’s interests in the current situation are clear but complex. First, it must ensure that the new Syrian government, along with the HTS forces behind it, does not pose a security threat. Second, Israel will work to influence Western perspectives on al-Sharaa, seeking to prevent undue pressure on itself to make territorial concessions. Finally, Jerusalem is trying hard to avoid being seen in the West as a destabilizing force in Syria or as an obstacle to regional stability.

Achieving these objectives will not be simple. The international community, exhausted by the prolonged Middle Eastern conflict now entering its 16th month, has little appetite for further escalation. As a result, Israel’s options are limited, and Netanyahu will need to navigate this shifting situation with caution.

For Israel, the question is not simply how to handle the tactical realities on the Golan Heights, but whether it can manage the broader strategic risks of a new era in Syria. In the coming months, as al-Sharaa’s government consolidates its power and attempts to stabilize the country, Israel will have to decide whether to continue its military presence in the buffer zone, whether it should enter negotiations over setting a recognized border, or take a more cautious, wait-and-see approach.

The stakes are high, and the future of the Middle East rests, once again, on an unpredictable path forward.

Yaakov Katz is the co-author of the forthcoming book “While Israel Slept” and is a senior fellow at JPPI, a global Jewish think tank based in Jerusalem.