|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Edited by: Fern Sidman

The Jewish community in Japan, though small in number, represents a rich tapestry of resilience, cultural integration, and historical significance. With a population of around 1,000-1,400 Jews, according to WiseVoter.com, Japan’s Jewish community today is primarily composed of expatriates and foreign residents. Despite its modest size, the community is well-organized and vibrant, with the Jewish Community of Japan (JCJ) serving as the country’s official affiliate of the World Jewish Congress.

The first Jewish individuals to set foot in Japan arrived in the 16th and 17th centuries as merchants employed by the Dutch and British navies. This period coincided with Japan’s era of cautious engagement with foreign powers before the imposition of its “closed door” (sakoku) policy, which restricted foreign interaction for over two centuries. During this time, Japan tightly controlled external trade through select ports, effectively stifling the development of any permanent Jewish community.

It wasn’t until 1854, with the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry and the subsequent signing of treaties to open Japan to international trade, that foreigners, including Jews, could re-establish themselves in Japan. These treaties marked the beginning of modern Japan’s relationship with the Jewish diaspora, as small Jewish communities began to form in port cities such as Yokohama and Nagasaki.

The late 19th century saw the establishment of organized Jewish communities in Japan, primarily in the cities of Yokohama and Nagasaki. Yokohama, located just south of Tokyo, became a hub for Jewish merchants and traders who capitalized on Japan’s rapid industrialization and expanding international trade networks.

At the same time, Jewish refugees fleeing Russian pogroms in the late 19th century found refuge in Nagasaki. These refugees played an essential role in building a vibrant Jewish community in the city. By the turn of the century, the Jewish population in Japan was growing steadily, largely driven by successive waves of immigration caused by unrest and persecution in Russia.

The outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) marked a significant moment for Jewish history in Japan. During the war, approximately 2,000 Russian Jewish soldiers were taken prisoner by Japan. Following their release at the war’s conclusion, many of these former prisoners remained in Japan and formed a Jewish community in Kobe, which would later become one of Japan’s most prominent Jewish centers.

The aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1905 and the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 triggered additional waves of Jewish migration to Japan. The relative openness of Japanese society, coupled with its growing economy, made cities like Kobe and Yokohama attractive destinations for Jewish immigrants seeking stability and opportunities.

By the end of World War I, the Jewish population in Japan had grown to a few thousand, with established communities scattered across the country’s major cities. However, the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 devastated Yokohama and displaced many Jewish residents, prompting a significant portion of the community to relocate to Kobe.

While Japan historically lacked the deep-rooted antisemitism that plagued many European nations, exposure to Russian anti-Semitic conspiracy theories and propaganda during Japan’s military intervention in Siberia (1918–1922) began to sow the seeds of antisemitic thought among some segments of Japanese society. Japanese troops stationed in Siberia encountered the infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a fabricated text purporting to expose a Jewish plot for global domination.

These antisemitic narratives began to take root in certain military and political circles in Japan, laying the groundwork for discriminatory policies in the years to come.

Japan’s formal alignment with Nazi Germany in 1940 under the Tripartite Pact further complicated the status of the Jewish community. Germany exerted pressure on its Axis partner to adopt antisemitic policies and crack down on Jewish residents. However, Japan’s approach to the so-called “Jewish Question” remained ambivalent and inconsistent.

In 1938, despite repeated demands from Nazi officials, Japan’s Five Ministers Council—the highest decision-making body in the country—chose to prohibit the expulsion of Jews from Japan. While this decision prevented large-scale atrocities against the Jewish population in Japan, it did not eliminate discrimination. Jewish residents were still subject to suspicion, surveillance, and bureaucratic hurdles.

However, Japan’s relative apathy toward Nazi-style antisemitism allowed many Jews to survive and even thrive in cities like Kobe, which became a safe haven for Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe. The story of Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese consul in Lithuania who issued thousands of visas to Jewish refugees against direct orders, stands as a testament to the humanitarian spirit displayed by some Japanese officials during this turbulent period.

Against direct orders from Tokyo, Sugihara issued between 2,100 and 3,500 transit visas to Jewish refugees in 1940, allowing them to escape Nazi-occupied Europe via Japan. His actions are often compared to those of Oskar Schindler and Raoul Wallenberg.

Sugihara’s heroism provided a lifeline to thousands of Jews, enabling them to travel through Japan to safety in other countries. His deeds remain one of the most celebrated humanitarian efforts during the Holocaust, and his legacy continues to symbolize the moral courage of individuals acting against oppressive systems.

As Japanese forces expanded their territories across East Asia and the Pacific, Jewish communities in cities such as Shanghai, Singapore, and Malaysia came under Japanese administration. While some Jews faced internment in detention or semi-internment camps—most famously in Hongkew, Shanghai—Japan largely maintained a policy of neutrality towards Jewish communities.

Financial hardship, however, became a severe problem for these Jewish populations. The influx of refugees from Europe during the interwar years had already strained resources, and wartime conditions further exacerbated their difficulties. Japan permitted Jewish relief organizations, such as the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), to operate within its occupied territories, providing vital assistance to Jewish refugees and communities.

In the post-war years, many Jewish survivors from Japanese-occupied territories emigrated to countries such as the United States, Canada, and Israel, seeking to rebuild their lives far from the trauma of war.

Japan’s Jewish population reached its peak during the American occupation (1945–1952) following World War II. Thousands of Jewish G.I.s and U.S. officials, including high-ranking figures in General Douglas MacArthur’s administration, were stationed in Japan.

Among them was Charles Louis Kades, a Jewish legal expert who played a key role in drafting Japan’s post-war constitution in 1946. Kades’ contribution helped shape Japan’s modern democratic framework, embedding principles of human rights, gender equality, and pacifism into the nation’s legal foundation.

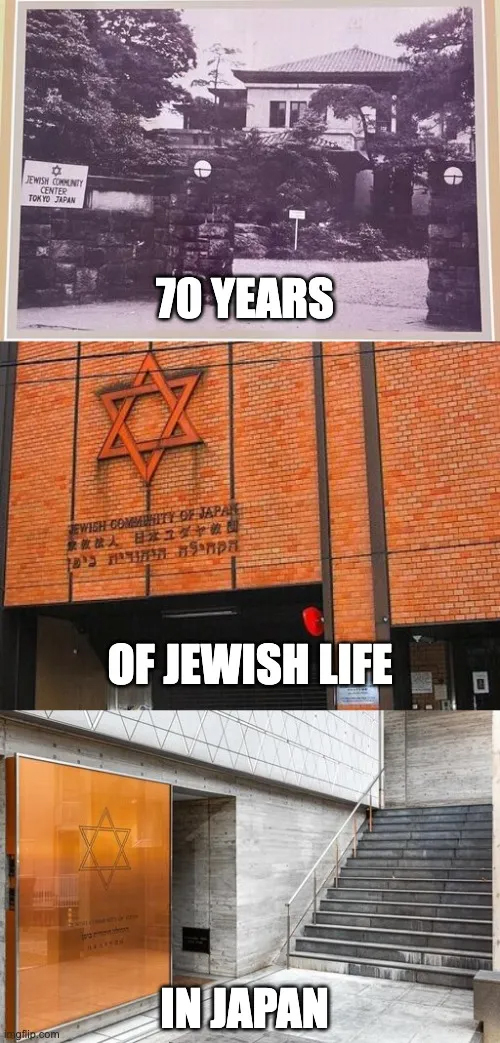

During this period, the Jewish presence in Japan was more visible and vibrant than ever. Synagogues, cultural centers, and Jewish social organizations flourished, providing a temporary golden age for Jewish life in Japan. However, as the American occupation ended in 1952, many Jewish personnel and their families returned home, leading to a sharp decline in the Jewish population.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Japan’s miraculous post-war economic recovery transformed the nation into a global financial powerhouse. This economic boom attracted foreign professionals, including many Jewish expatriates working in industries such as finance, commerce, and international trade.

As Tokyo solidified its status as a major global financial center, the Jewish community in the capital grew significantly. New institutions were established, including synagogues, community centers, and kosher facilities, allowing Jewish residents and visitors to maintain their cultural and religious practices.

According to Hebrew University demographer Sergio DellaPergola, Japan’s Jewish population represents one of the smaller Jewish communities in the world. Concentrated primarily in Tokyo and Kobe, this community has carved out a meaningful presence in a country where Judaism remains largely unfamiliar to the general population.

The majority of Jews in Japan reside in Tokyo, the nation’s sprawling capital, while smaller Jewish enclaves exist in cities such as Kobe. The community is composed mostly of expatriates and temporary residents, including business professionals, diplomats, educators, and students. Unlike traditional Jewish communities in Europe or the Americas, Japan’s Jewish population lacks deep historical roots in the region, yet it remains well-organized and actively engaged in both local and global Jewish affairs.

At the heart of Jewish life in Japan is the Jewish Community of Japan (JCJ), headquartered in Tokyo. Serving as the communal representative body, the JCJ plays a pivotal role in ensuring that both long-term residents and short-term expatriates have access to religious, cultural, and social resources.

The JCJ is affiliated with both the Euro-Asian Jewish Congress (EAJC) and the World Jewish Congress (WJC), allowing the Jewish community in Japan to maintain strong connections with Jewish populations worldwide. This affiliation fosters not only a sense of belonging but also access to international support and resources.

Beyond the JCJ, several Jewish organizations operate in Japan, primarily out of Tokyo. They include the Japan-Israel Women’s Welfare Organization, the Japan-Israel Friendship Association and the Japanese Women’s Group.

These organizations contribute to humanitarian causes, Jewish education initiatives, and cross-cultural understanding, serving both the Jewish community and broader Japanese society.

Jewish religious life in Japan is primarily centered in Tokyo and Kobe, with three active synagogues serving the community. They are the Beth David Synagogue (Tokyo) Known for its pluralistic approach, Beth David serves a multinational congregation and emphasizes inclusivity over denominational alignment. Kobe Synagogue (Kobe) This is an important historical site and an enduring symbol of Jewish presence in Japan. Chabad Centers in Tokyo and Kobe. They are operated by the Chabad-Lubavitch movement and these centers provide essential religious services, community events, and educational opportunities.

Additionally, Jewish ritual life in Japan is supported by the presence of a mikveh (ritual bathhouse) and a chevre kadisha (Jewish funeral organization), ensuring that lifecycle events are conducted in accordance with Jewish tradition.

Maintaining kosher dietary practices in a predominantly non-Jewish society can be challenging, but Tokyo and Kobe offer access to kosher food options. Specialized kosher products, imported goods, and locally certified items are available in select stores and through community resources. The Chabad centers in both cities also play an essential role in providing kosher food services, especially during major Jewish holidays.

While kosher restaurants remain rare, pre-packaged kosher meals and community-organized food events ensure that Jewish residents and visitors can maintain their dietary laws.

Jewish education in Japan is modest but meaningful. While there are no full-time Jewish day schools, the Jewish Community of Japan (JCJ) operates biweekly classes for adolescents and a Sunday school for younger children.

Both the JCJ and Chabad also offer adult education programs, including Hebrew language lessons and classes on Jewish culture, traditions, and religious practices.

At the university level, Japan provides opportunities for Judaic studies. Notably, Waseda University’s Institute of Social Sciences offers a Jewish Studies program.

The Japan Society for Jewish Studies publishes an academic journal titled Yudava-Isuraeru Kenkvu (“Studies on Jewish Life and Culture”), contributing to scholarly discourse on Jewish history and culture.

While Jewish educational infrastructure is limited, these programs ensure that members of the community, both young and old, remain connected to their heritage.

Japan hosts several important Jewish heritage and memorial sites, reflecting the nation’s unique role in Jewish history. They include the Chiune Sugihara Memorial Museum which is located in Yaotsu, Gifu Prefecture. This museum honors Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese diplomat previously mentioned in this article who issued thousands of transit visas to Jewish refugees during World War II, saving them from Nazi persecution. The museum serves as both a historical archive and an educational center, reminding visitors of Sugihara’s extraordinary humanitarian efforts.

The Holocaust Memorial at Hiroshima is situated in the city forever marked by the atomic bomb and this memorial serves as a poignant symbol of shared human suffering and resilience.

These sites not only commemorate Jewish history in Japan but also serve as bridges of cross-cultural understanding between Jewish and Japanese narratives.

Visitors to Japan will find a welcoming and resourceful Jewish community, especially in Tokyo and Kobe. Whether it’s attending services at Beth David Synagogue, seeking kosher food through Chabad, or exploring significant historical landmarks like the Sugihara Memorial Museum, Jewish visitors have access to essential resources for maintaining their traditions while in Japan.

With active community organizations like the Jewish Community of Japan (JCJ), educational initiatives, kosher resources, and vibrant religious centers, Jewish life in Japan is sustained through dedication and cultural exchange.

Moreover, landmarks such as the Chiune Sugihara Memorial Museum stand as enduring symbols of humanitarianism and moral courage, cementing Japan’s unique role in Jewish history.

While small in numbers, the Jewish community in Japan continues to thrive, offering a compelling example of how faith, identity, and cultural heritage can endure and flourish even in the most unexpected of places.