|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Edited by: Fern Sidman

In 1998, the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art were adopted by the United States and 43 other countries, setting an international framework for handling claims regarding Nazi-looted art. These principles emphasized the importance of fair and just solutions for families seeking restitution of art stolen during the Holocaust and recommended the creation of alternative dispute resolution processes outside conventional court systems. However, despite being the driving force behind these principles, the United States has yet to establish its own restitution panel, a gap that has become increasingly glaring over the past 25 years. As was recently reported by The New York Times, recent discussions have reignited hopes for progress on this long-overdue issue.

The Washington Principles emerged out of the recognition that traditional court systems often fall short when handling claims related to Nazi-looted art. Courts, particularly in the United States, frequently base their rulings on procedural technicalities such as statutes of limitations, which can prevent claimants from having their cases fully heard, according to the information provided in The New York Times report. These technical barriers often overlook the broader moral considerations inherent in restitution claims, such as the historical injustice suffered by families whose valuable cultural property was stolen during one of history’s darkest periods.

To address these shortcomings, six countries—Britain, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Austria—established dedicated restitution panels. These tribunals operate outside the rigid confines of traditional courts and are specifically tasked with considering the moral and historical dimensions of restitution cases, The New York Times report indicated. These panels have become the primary venues where many claims involving Nazi-looted art are resolved.

Yet, the United States has not followed suit, despite being instrumental in advocating for these principles on the global stage.

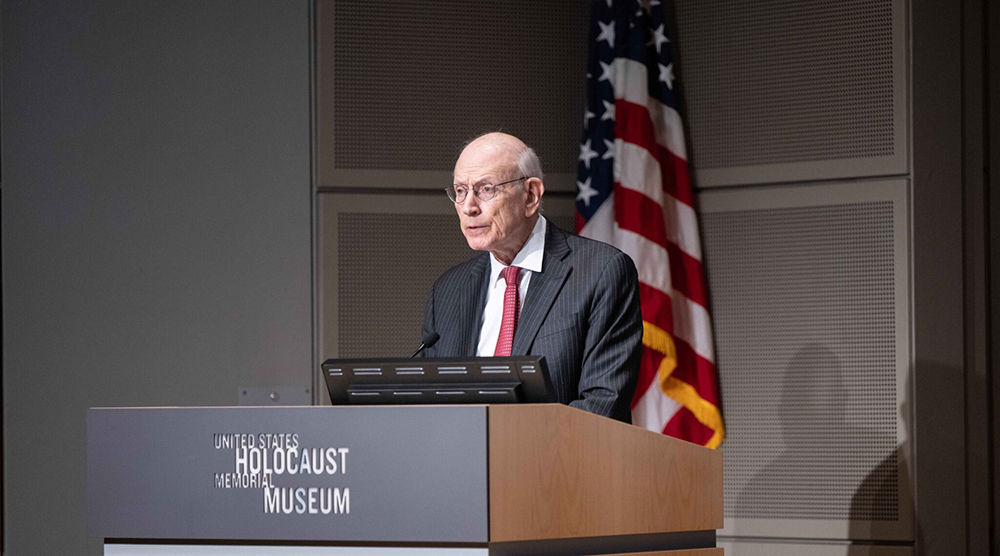

The absence of a restitution panel in the United States is not due to a lack of effort or advocacy. As reported by The New York Times, Stuart Eizenstat, the former U.S. Secretary of State’s Special Adviser on Holocaust Issues, who spearheaded the creation of the Washington Principles, has been a tireless advocate for their implementation.

One key reason cited by Eizenstat is the structural difference between American and European art institutions. The New York Times report said that in Europe, museums are often state-owned and fall under the jurisdiction of national ministries of culture. These governmental bodies can mandate compliance with restitution policies, ensuring a consistent and enforceable approach across state-run institutions.

In contrast, most American museums are privately owned and operated, receiving limited direct oversight from the federal government. As Eizenstat explained to The New York Times, “The basic point is that we don’t have a Ministry of Culture, right? There’s no governmental entity to oversee or set the rules for these commissions.”

This decentralized structure makes it significantly more challenging to establish a restitution panel with the authority to mediate and enforce resolutions across the diverse landscape of American museums.

The disparity between U.S. policy and its advocacy for restitution tribunals in other countries was recently noted by Olaf S. Ossmann, a lawyer specializing in art restitution claims. The report in the New York Times noted that in an Art Newspaper essay, Ossmann argued that the failure to create a U.S. restitution panel after 25 years is both surprising and indefensible.

“It seems almost unbelievable,” Ossmann wrote, “when the U.S. State Department rightly makes exactly this demand to various European and non-European governments but does not take action in its own country after more than 25 years.”

This critique reflects growing frustration among legal experts and claimants who have long awaited a dedicated platform for resolving disputes over Nazi-looted art in the U.S.

For families seeking to reclaim art stolen during the Nazi era, the U.S. legal system can be a daunting arena. The New York Times reported that claimants face expensive litigation costs and are often met with procedural defenses, such as statutes of limitations, that prevent their cases from being fully considered on their merits.

As Gideon Taylor, president of the World Jewish Restitution Organization and the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, told The New York Times: “The goal here is to look at the justice and the fairness of who owned it and what happened, not to rely on a technical legal framework for an event that’s of unique historic proportions.”

This sentiment reflects a key criticism of the U.S. legal approach: that procedural technicalities often overshadow the moral imperative to address the theft of cultural property during one of history’s darkest periods.

Despite efforts to address some of these challenges through legislation like the HEAR Act of 2016 (Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act), which created a national six-year statute of limitations for claims, many obstacles remain entrenched. According to the information contained in The New York Times report, the HEAR Act sought to ensure that the clock on restitution claims begins only when a claimant has reason to know of the Nazi theft of their family’s art. However, even with this legislative fix, the court system often remains an uneven playing field for claimants.

A notable example, as highlighted by The New York Times, is the legal battle between the heirs of a German-Jewish department store owner and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, over a painting by Bernardo Bellotto. The painting was sold in 1938, and the heirs argued that the sale occurred under duress during a period of severe economic and social hardship for German Jews.

The museum countered that the sale was fair and legitimate and that the case was adjudicated on its merits rather than dismissed on procedural grounds. Federal courts ultimately sided with the museum, and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the case.

While the museum insists that its defense was based on factual analysis rather than technicalities, the heirs argue that the museum leaned heavily on legal defenses instead of engaging with the moral and historical significance of the claim, as was explained in The New York Times report.

This case encapsulates the broader issue: courts, bound by rigid legal frameworks, often cannot fully address the historical injustices and moral considerations that restitution claims demand.

The Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) has weighed in cautiously on the subject of a U.S. restitution panel. While the association emphasizes its commitment to transparency and fairness in handling restitution claims, it stops short of endorsing the creation of a formal tribunal.

In a statement cited by The New York Times, the AAMD noted: “In the rare circumstance that a museum — usually after extensive research — determines that a claim is not supported by the facts, litigation has occurred. Museums have an obligation to conduct that litigation in a responsible manner, including raising affirmative defenses if they are merited. They are not ‘technical,’ but are deeply rooted in our legal system to protect the rights of litigants.”

This position illustrates the tension between museums’ legal responsibilities and the moral imperatives of restitution. Museums are obligated to defend their holdings, yet this often leaves claimants feeling sidelined and disillusioned by the process.

The report in The New York Times noted that while the AAMD has been part of preliminary discussions with Stuart Eizenstat and State Department representatives about a potential restitution panel, the association clarified that this is not an active topic of discussion at present.

One of the primary obstacles to establishing a restitution panel in the U.S. is funding. As The New York Times reported, questions remain about who would cover the operational costs of such a tribunal.

Eizenstat suggested that retired judges could serve on the panel, potentially even without pay. However, The New York Times report indicated that this voluntary approach may not be sustainable in the long term, especially given the volume and complexity of potential cases.

Possible monitoring mechanisms could include federal or state grants, private endowments from philanthropic organizations and fees paid by participating museums or claimants.

The details remain unclear, but Eizenstat’s optimism suggests that creative solutions could address the financial hurdles if there is enough political and institutional will.

The HEAR Act, enacted in 2016, was a landmark piece of U.S. legislation designed to address barriers to restitution claims by creating a uniform six-year statute of limitations that begins only when a claimant becomes aware of their family’s art being looted by the Nazis.

However, as Ossmann explained to The New York Times, the HEAR Act, while groundbreaking, has had limited applicability. Ossmann noted, “The HEAR Act opened a new door, but is relevant in only 10 out of 100 cases.”

This limited impact arises from the HEAR Act’s focus on a narrow set of procedural issues, while failing to address other major hurdles, such as the legal doctrine of laches.

Laches refers to the idea that a claim can be rejected if it was unreasonably delayed, especially if the art in question was publicly displayed for decades without challenge. The New York Times report said that courts and panels often invoke this doctrine to dismiss claims, arguing that claimants failed to act in a timely manner despite the art’s visibility in public collections.

Advocates for reform argue that laches is wielded too often as a tool to block valid claims, and they hope that this issue will be addressed when Congress considers renewing the HEAR Act, which is scheduled to sunset in 2026, according to the report inThe New York Times.

While restitution panels have played a significant role in resolving claims, they are not without their critics. One of the major criticisms, as highlighted by The New York Times, is the lack of consistency in their decisions, even in cases that seem strikingly similar.

A notable example involves the case of Curt Glaser, a prominent art collector and former head of Berlin’s State Library who was forced to sell his art collection at two auctions in Berlin in 1933 before fleeing Germany.

In 2009, the British Spoliation Panel rejected a claim by Glaser’s heirs for drawings held by a museum in the UK.

The New York Times reported that just a year later, in 2010, the Dutch restitution panel reached an opposite conclusion, recommending the return of a painting sold by Glaser under nearly identical circumstances.

Such discrepancies have left many claimants frustrated and disillusioned with the restitution process.

Benjamin Lahusen, a professor of private law and modern legal history at the European University near Frankfurt, told The New York Times: “The criticism is repeatedly raised that allegedly similar cases have given rise to divergent decisions. The problem is said to apply at both the international and national level.”

These inconsistencies stem from differing interpretations of critical issues, such as determining whether a sale was made under duress and whether the seller received fair market value. Another issue is whether the sale occurred before or after Nazi invasion, which can significantly affect the panel’s interpretation of coercion.

This lack of uniformity has led to calls for greater standardization and coordination across restitution bodies.

The discrepancies and fragmented approach to restitution have sparked discussions about the creation of a centralized restitution body, possibly at the European Union level. Such an organization could serve as an umbrella tribunal, offering more coherent and uniform decisions across borders.

As reported by The New York Times, the European Parliament recently commissioned Evelien Campfens, a lawyer and lecturer on cultural heritage law at the University of Amsterdam, to study the ongoing issues surrounding restitution.

Campfens’ recommendations include encouraging rigorous provenance research to trace the history of art pieces and discourage the sale of cultural objects with tainted provenance and establishing a centralized body to enhance coordination and provide resources for provenance research across jurisdictions.

Campfens emphasized to The New York Times: “Setting up a knowledge center for provenance research would enhance coordination and provide consistency in decisions.”

This centralized approach could address one of the core issues plaguing current restitution efforts: the fragmentation and lack of a cohesive strategy across different national panels.

The landscape of Nazi-looted art restitution remains fragmented, with different institutions—and even different countries—adopting divergent approaches. According to the information in The New York Times report, some institutions opt to restitute stolen art, others provide financial compensation, and many still refuse to take any action at all.

As one expert noted: “Some are to be found in Austrian institutions, some in Germany, others in the United States and France. Some institutions restitute, others pay a compensation. Others don’t do anything.”

This lack of uniformity creates frustration for claimants, who must navigate a patchwork of national policies, institutional guidelines, and legal frameworks.

Yet restitution is not solely about addressing the injustices of the past—it carries significant implications for the present. As the expert emphasized: “By restituting cultural property we address the past, but even more the present. We are seeking to make a difference today.”

This highlights the moral imperative driving restitution efforts: that it is not merely about correcting historical wrongs but also about reaffirming principles of justice and accountability in the present.

One notable development highlighted by The New York Times in their report is the increased sharing of decisions between national restitution panels. According to Eizenstat, this growing transparency could lay the groundwork for a body of legal precedents.

Precedents are essential in creating consistency, as they provide guidance for future cases and reduce the likelihood of contradictory rulings in similar claims. While the process is still in its early stages, Eizenstat expressed optimism that this collaborative approach could help address the fragmentation seen across different jurisdictions.

In Germany, there are further reasons for cautious optimism. Matthias Weller, professor of restitution law at the University of Bonn, pointed to a recent measure that allows claimants to submit their cases to a binding arbitration court.

“Until now, the parties had to agree on nonbinding mediation,” Weller explained to The New York Times.

Binding arbitration represents a significant shift, as it offers a more definitive resolution process for claimants who may have otherwise faced prolonged uncertainty. However, The New York Times reported that concerns remain about how proposed legislation might impact the claims process, with some experts worried that it could inadvertently create new barriers rather than removing existing ones.

In March 2024, 28 countries signed an agreement aimed at strengthening the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. This agreement, titled “Best Practices for the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art,” was negotiated by Eizenstat and represents a critical milestone in the global restitution movement.

As The New York Times report indicated, one of the key recommendations of the Best Practices agreement is an explicit call for countries to create independent panels capable of adjudicating restitution claims fairly and transparently.

This renewed commitment comes at a time when public interest in Holocaust restitution cases is rising, and the volume of claims in countries like the United States is increasing.

Despite its leadership in establishing the Washington Principles, the United States has yet to create its own dedicated restitution panel. As reported by The New York Times, advocates such as Gideon Taylor, believe that the time is ripe for meaningful action in the U.S.

“With the growing international consensus demonstrated by the Best Practices, an increasing number of claims in the U.S., and rising public interest, now is the moment for establishment of a commission or similar mechanism at the Federal or State level that will not simply apply restrictive law, but rather find historical justice for victims of Holocaust-era looting,” Taylor said.

A restitution panel in the United States would offer claimants an alternative pathway to litigation, which is often prohibitively expensive and heavily reliant on technical legal defenses, such as statutes of limitations and the doctrine of laches.

While existing U.S. laws, such as the HEAR Act of 2016, have addressed some barriers, they have not fully eliminated the challenges claimants face in courtrooms. The New York Times report said that a dedicated panel could prioritize fairness and historical context over procedural technicalities, allowing claims to be adjudicated with sensitivity to the unique circumstances of Nazi-era art sales and confiscations.

The push for a U.S. restitution panel is not just a legal discussion—it’s a moral imperative. The theft of cultural property during the Nazi era rep

resents an enduring wound, and the restitution of stolen art is not merely a financial issue but a matter of justice, recognition, and accountability.

resents an enduring wound, and the restitution of stolen art is not merely a financial issue but a matter of justice, recognition, and accountability.

The establishment of a U.S. restitution panel would signal a renewed commitment to historical justice, aligning the nation with the principles it once championed on the global stage.

While challenges remain—particularly around funding mechanisms, institutional cooperation, and legislative support—the growing international consensus offers a unique window of opportunity to address these long-standing injustices.

As Gideon Taylor emphasized to The New York Times, the moment for action is now: “We are seeking to make a difference today.”

The path forward will require political will, institutional collaboration, and a steadfast commitment to historical justice, but the groundwork has been laid. The question is whether the United States will rise to meet this moment.