|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

As several museums mark the 100th anniversary of the famed novelist and writer’s passing, experts told JNS that Kafka remains very relatable today.

By: Vita Fellig

The German-Jewish writer Franz Kafka, who died 100 years ago at age 40, is on the short list of people whose name has become an eponymous adjective. The term “Kafkaesque” suggests bureaucratic folly, but Kafka, whose life and work is being celebrated in major exhibitions in Israel, Germany and New York, should also be thought of specifically as a Jewish writer, experts told JNS.

Stefan Litt, curator of the humanities collection at the National Library of Israel and co-curator of the library’s exhibit “Kafka: Metamorphosis of an Author” (through June), told JNS that the exhibit displays never before seen personal letters, notebooks and manuscripts of Kafka’s.

“The items have been chosen in order to depict Kafka’s world, his social contacts, his biographic background and his literary work,” Litt said. “Many people have a vague idea who exactly he was, and the exhibit is seeking to provide a better understanding of the author and his work.”

The “imaginary worlds” of Kafka “describe encounters of individuals with a world full of powers which are not predictable but almighty, not transparent but decisive for the fate of many human beings,” he added. “Many of our contemporaries experience these encounters and will experience them also in the future.”

The Kafka collection at Israel’s National Library in Jerusalem is one of three leading collections of the author’s work, according to Litt.

“I think knowing that Kafka was Jewish possibly brings Jewish Israelis closer to him than others in different countries,” he told JNS.

Kafka’s work has also influenced Israeli art and culture, although the author’s Jewish identity was not conspicuous, according to Litt.

“We know that Kafka was aware of his Jewish roots,” he said. “Like many other Jewish contemporaries of his, he did not express his identity very openly.”

Shelley Harten, curator at the Jewish Museum of Berlin’s exhibit “Access Kafka” (through May), told JNS that the writer was interested in Judaism as a cultural community.

“He almost never explicitly wrote about Judaism in his literary works, although some of his stories can be associated with Jewish themes, such as ‘Jackals and Arabs’ or ‘Before the Law,’” Harten said. “Some of his letters and diary entries concerned with Judaism are of a literary quality.”

The writer’s Judaism, “though not in a religious sense, was part of his socialization and cannot be extricated from his work, just as the German language or the city of Prague made him the writer that he was,” Harten said.

The Berlin museum’s exhibit combines drawings and letters by Kafka with artwork of contemporary artists to highlight the author’s literary legacy.

“Kafka deals with universal topics on an individual scale. In his texts he describes ambivalent and paradoxical situations that still apply to our lives today,” she told JNS. “The exhibition focuses on the topics of access and denied access that have been central to Kafka’s work, biography and even to the availability of his manuscripts after his death.”

The German show also includes “famous drawings of men behind fences or in front of windows and manuscripts from the unfinished novels ‘The Castle’ and ‘The Man Who Disappeared,’ in which access to physical and social spaces is denied,” she added. “The artworks by contemporary artists expand on the topic of accessibility and take Kafka’s paradoxical approach into the present.”

‘Enduring appeal’

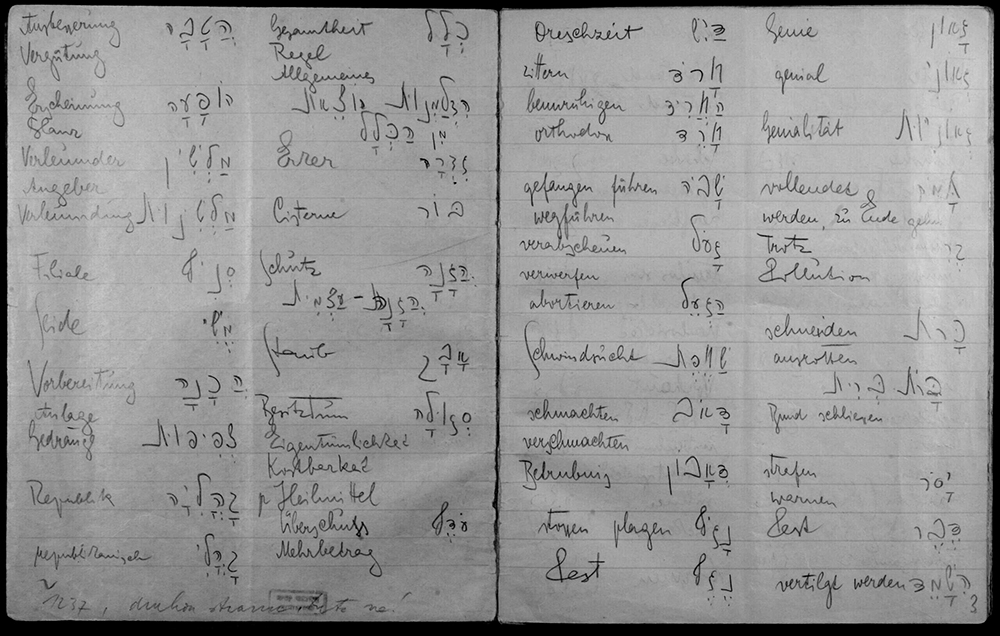

The Morgan Library & Museum in Manhattan is also showing a Kafka exhibit (through April 13), which includes “the notebooks he used when studying Hebrew” and Andy Warhol’s Kafka portrait from his 1980 “Ten Portraits of Jews of the 20th Century” series.

“When Franz Kafka died of tuberculosis at the age of 40, in 1924, few could have predicted the influence his relatively small body of work would have on every realm of thought and creative endeavor over the course of the 20th century and into the 21st,” the museum states.

Aaron Carpenter, a visiting assistant professor at Allegheny College in Meadville, Pa., who just completed his doctorate in German studies at the University of Washington, told JNS that Kafka’s work has become popular with a younger generation through platforms like TikTok.

“Kafka is very self-deprecating and self-loathing, in some ways, which I think is very relatable,” said Carpenter, who has written on Kafka, Judaism and Yiddish. “He speaks to an insecurity within all of us, because he could be very romantic in his writings, but in person, he wasn’t good at showing his feelings or emotions.”

“I think for a lot of young people today, especially coming out of the COVID era with more time being spent online, they relate to Kafka’s neurotic tendencies,” he said.

Carpenter told JNS that Kafka’s work has an enduring appeal because it was written during a turbulent historical period—something to which people relate today.

“Kafka lived through World War I and there was a lot of uncertainty in the breakup of the Habsburg empire,” he said. “What does it mean to be a German-speaking Jew in the newly formed Czechoslovakia? There were many new technological and social changes during that time.”

In the wake of social upheaval following the financial crisis in 2008 and the pandemic in 2020, “we connect with that uncertainty expressed in his work,” he said.

(JNS.org)