|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Edited by: TJVNews.com

It’s impossible to ignore the allure of the Chrysler Building, a jewel of New York’s skyline that epitomizes Art Deco grandeur. For Aby Rosen, the flamboyant German émigré and co-founder of RFR Holding, the temptation was irresistible.

Known for his penchant for reviving historic architectural gems such as Lever House, the Seagram Building, and the Gramercy Park Hotel, Rosen saw in the Chrysler Building a chance to add another trophy to his illustrious portfolio. His approach to real estate has always been theatrical, blending high-profile renovations with celebrity chefs and bold art installations, as detailed in a recently published report at Curbed.com. When the Chrysler Building hit the market in 2019, Rosen, alongside Austrian firm Signa Holding, seized the opportunity to purchase the iconic structure for a mere $151 million—a fraction of the $800 million that the Abu Dhabi Investment Council had paid for a majority stake a decade earlier.

Rosen’s fascination with the Chrysler Building was more than business; it was deeply personal. As he told the New York Post at the time, he viewed the skyscraper as a “Sleeping Beauty” in desperate need of revitalization. The Chrysler’s whimsical steel gargoyles, opulent Moroccan marble lobby, and luminous spire—once an architectural coup that made it the tallest building in the world for a fleeting moment—perfectly matched Rosen’s over-the-top aesthetic. As Curbed.com reported, the acquisition felt like a quintessential Rosen move, one steeped in glamour and audacity. But the purchase came with significant baggage: a ground lease with Cooper Union, the private art and engineering college that owned the land beneath the Chrysler Building.

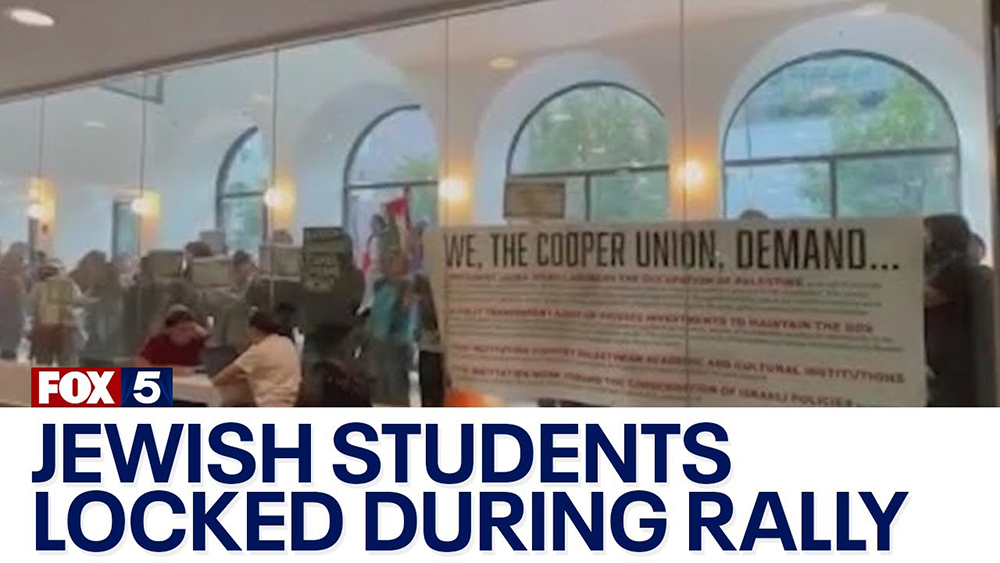

In October of this year, The Jewish Voice reported that an administrator at Cooper Union was under fire for her public endorsement of a vigil commemorating Palestinian “martyrs” on the anniversary of Hamas’ deadly October 7 attack on Israel. Athena Abadilla, director of residential life and community development at the university, commented in support of a vigil organized by the campus chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP), drawing widespread criticism for glorifying violence and fueling tensions on campus.

On October 21st, The Jewish Voice reported that The Zionist Organization of America, the Israel Law Center, the Betar Zionist Movement, Shields of David and other Jewish organizations were advocating for the resignation of Jamie Levitt, chairman of Cooper Union. “This demand comes in response to repeated acts of heinous antisemitism” at university where “students and faculty gathered to celebrate acts of jihad and praise terrorists,” the organizations said in a joint statement on Oct. 16. “Nothing is done, and nothing changes. We demand that Jamie Levitt resign immediately as chairman of Cooper Union,” said Nitsana Darshan Leitner of Shurat HaDin.

In November of 2023, The Jewish Voice also reported that Jewish students at Cooper Union expressed deep concerns about their safety on campus following a disturbing incident when they were locked inside the university’s library as pro-Hamas protesters pounded on doors and windows. Approximately 50 students, including a small group of Jewish students, found themselves barricaded inside the library after a Cooper Union staffer locked the doors as protesters entered the building. Demonstrators, some carrying Palestinian flags and signs reading “Zionism Hands Off Our Universities,” descended on the library.

This ground lease was more of a curse than a blessing. According to the information provided in the Curbed.com report, Cooper Union’s financial model relied on income from the lease, and in 2018, just before RFR’s acquisition, the rent skyrocketed from $7.78 million to $32.5 million annually. Worse yet, it was slated to climb to $41 million by 2028. The building’s office rents couldn’t cover these astronomical costs, let alone fund the substantial upgrades the aging structure required. The financial strain was immediate, and the Chrysler Building, long considered a “charming money pit,” became a high-stakes gamble for Rosen and Signa.’

Despite the mounting challenges, Rosen initially maintained his bullish confidence. His reputation for transforming struggling properties into thriving cultural hubs had served him well in the past. However, as the Curbed.com highlighted, the timing of the acquisition was disastrous. The office market had already begun to falter, and the pandemic’s impact exacerbated the strain on older, ground-leased buildings like the Chrysler. By October 2024, RFR had fallen $21 million behind on rent, forcing Rosen to relinquish control of the building.

For many in New York’s real estate circles, Rosen’s loss of the Chrysler Building seemed inevitable. As one executive told Curbed.com, the deal raised eyebrows from the start, with skeptics questioning whether RFR had a viable plan to manage the building’s financial challenges. Others viewed it as emblematic of Rosen’s broader approach: taking on high-profile properties with immense potential but equally immense risks. The saga, rife with court battles between Rosen and captivated industry insiders.

The Chrysler Building’s downfall was not an isolated incident for Rosen. As the Curbed.com report indicated, the past few years have seen several high-profile losses for the once-unstoppable real estate magnate. In 2020, RFR lost the ground lease for Lever House, another jewel in its portfolio. Two years later, Rosen surrendered the Gramercy Park Hotel, a beloved Manhattan landmark. His relentless optimism, described by friend André Balazs as “part of his charm,” was no match for the harsh realities of a declining office market.

Critics argue that Rosen’s strategy of “overpaying” for properties and attempting to enhance their appeal through art and design has backfired in the current economic climate. As a commercial broker told Curbed.com, “They put some lipstick on the pig, some art in there, try to leverage it. But right now, it’s not panning out in a number of his buildings.” Rosen’s penchant for dramatic investments may have secured him a reputation as a risk-taker, but the Chrysler Building’s saga illustrates the perils of high-stakes real estate in an increasingly unforgiving market.

Constructed in 1928 under the visionary direction of car magnate Walter P. Chrysler, the skyscraper was born out of audacious ambition. Chrysler commandeered the project, enlisting architect William Van Alen to replace the originally planned Moorish terra-cotta topper with a sleek, chrome-steel crown. This daring design decision cemented the building’s reputation as a brashly commercial and avant-garde masterpiece. For decades, it reigned as a prime piece of real estate, hosting elite gatherings at the famed Cloud Club. But as the Curbed.com report explained, the building’s golden era faded by the 1970s, when tenants such as Texaco began relocating to the suburbs, rising operational costs mounted, and foreclosure loomed.

The Chrysler Building’s allure has continuously lured investors, sometimes to their detriment. Sol Goldman, one of its owners in the 1960s, confessed to The New York Times that the property became a source of sleepless nights before its loss in the 1970s. The building’s complicated legacy persisted, with Curbed.com chronicling how Tishman Speyer rescued it from foreclosure in the late 1990s, invested $100 million in renovations, and successfully turned a profit. Even then, the building’s operational complexities, including small offices, inflexible floor layouts, and aging infrastructure, remained persistent hurdles.

Curbed.com reported that Rosen aimed to stabilize the building within three to five years, reopen the legendary Cloud Club, and attract a new wave of tenants willing to pay premium rents. His determination was unwavering, with reports of him discussing the Chrysler obsessively during personal vacations spanning Norway, Japan, and St. Barts. Yet, even his resourceful reputation could not escape the reality of a punishing ground lease set to escalate rents from $8 million to $30 million annually.

The Chrysler’s landmarked status, a testament to its historical and architectural significance, adds another layer of complexity. As Curbed.com revealed, this designation imposes restrictions and additional costs on renovations, making modernization efforts both intricate and expensive. Despite these obstacles, Rosen remained undeterred, leveraging his ability to attract high-profile collaborators and tenants in an attempt to make the building viable.

However, the structural and financial challenges of the Chrysler Building reflect broader trends in the real estate industry. As the report at Curbed.com pointed out, New York City’s office market has evolved, with tenants increasingly favoring state-of-the-art buildings that offer large, flexible floor plates and cutting-edge amenities. The Chrysler, with its small floor plates of around 5,000 square feet at the upper levels and cranky HVAC systems, struggles to compete in this modern landscape.

As detailed by Curbed.com, Rosen’s vision encompassed not just comprehensive restoration but also a transformation of the building’s commercial and aesthetic appeal. High-profile partnerships were at the heart of this plan, with restaurateurs such as the Major Food Group and Stephen Starr considered for multiple dining concepts, including an upscale restaurant in the legendary Cloud Club. Architects David Rockwell and Ken Fulk were enlisted to redesign the arcade and upper-floor amenities, which had previously housed famed photographer Margaret Bourke-White’s office.

Rosen also filed plans with the Landmark Preservation Commission to modernize the building, including the addition of a glass safety wall near its iconic chrome eagles. These moves were part of a larger $170 million investment in repairs and upgrades, covering everything from elevator replacements to architectural designs. However, as the Curbed.com report said, Cooper Union, the landowner, disputed the figure, estimating the investment closer to $80 million.

Central to Rosen’s strategy was renegotiating the building’s ground lease with Cooper Union. As the Curbed.com report noted, the escalating rent presented a significant financial strain, with initial terms set to increase annual rent dramatically. While Rosen believed that a workable agreement could be reached, others, such as Tishman Speyer, doubted Cooper Union’s willingness to renegotiate. Nevertheless, Rosen pursued negotiations in 2021 and 2023, reportedly offering a $300 million lump sum to reduce annual rent to under $15 million, alongside revenue-sharing terms. Yet, these efforts failed to yield a mutually satisfactory deal, with RFR citing Cooper Union’s inflexibility as a major roadblock.

On November 6th of this year, The Jewish Voice reported that a Manhattan judge ruled that tenants of the Chrysler Building are to pay their rent directly to Cooper Union, bypassing the current leaseholder, Aby Rosen’s RFR Holding, in a decision marking a significant setback for Rosen. As The New York Post reported, Judge Jennifer Schechter of the Manhattan Supreme Court also made it clear that Rosen should refrain from attempting to interfere in Cooper Union’s management of the historic Art-Deco skyscraper. This decision follows a legal battle between Rosen and the university, which owns the land beneath the Chrysler Building.