|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

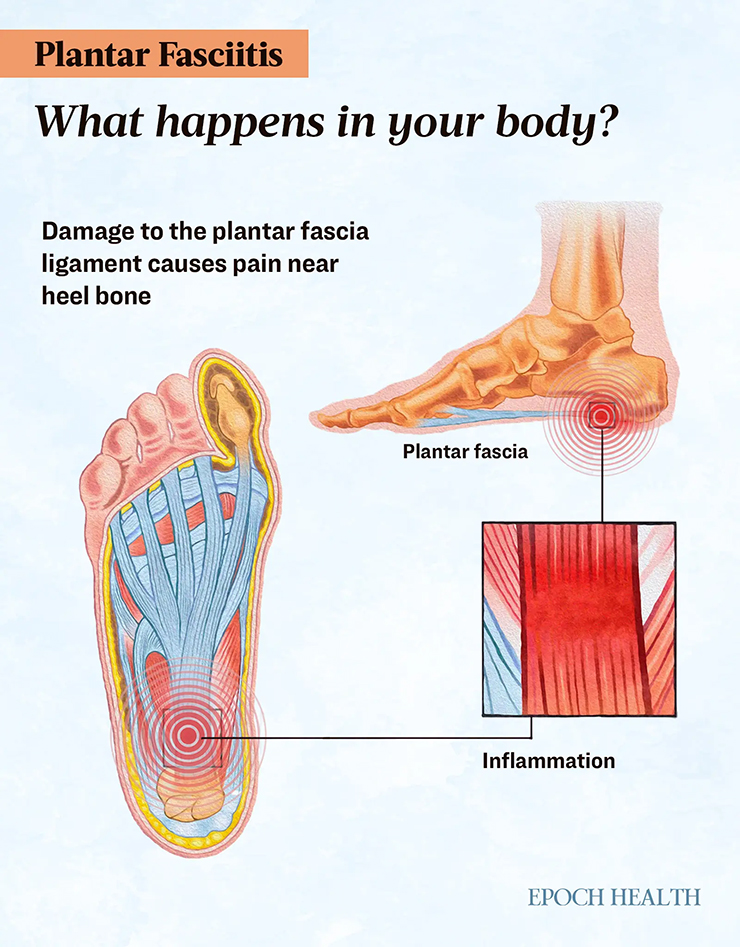

Affecting about 10 percent of the U.S. population, plantar fasciitis involves pain in the thick band of tissue that runs from the toes to the heel.

By: Mercura Wang

Plantar fasciitis is characterized by pain originating from the plantar fascia, a thick tissue band that runs from the heel bone to the base of the toes. This condition typically involves pain at the attachment site of the plantar fascia to the calcaneus (heel bone). In the United States, plantar fasciitis is the leading cause of heel pain seen in outpatient settings, with an estimated 1 million to 2 million patient visits each year attributed to it.

Although the exact incidence and prevalence by age are unknown, plantar fasciitis accounts for about 10 percent of injuries in runners and 11 percent to 15 percent of all foot-related symptoms that necessitate medical attention. It affects approximately 10 percent of the general population in the United States. Its other names include policeman’s heel, heel pain syndrome, and runner’s heel.

Acute can be triggered by a specific injury and is characterized by a sudden onset of symptoms that typically resolves in around six months.

Chronic plantar fasciitis is when symptoms persist beyond six months. Sometimes, symptoms worsen over time.

What Are the Symptoms and Early Signs of Plantar Fasciitis?

In the early stages of plantar fasciitis, pain often subsides quickly when weight is taken off the foot. However, as the condition progresses, it may take longer for the pain to resolve. Without treatment, the plantar fascia can partially tear away from the heel, leading the body to fill the tear with calcium and eventually forming a heel spur. Heel spurs are also seen in people without plantar fasciitis.

Recognizing symptoms early is crucial for timely intervention and effective management. People with plantar fasciitis may experience pain anywhere along the length of the plantar fascia. The severity and duration of symptoms can vary between individuals, with some experiencing debilitating symptoms.

Common symptoms of plantar fasciitis include the following:

Pain on the bottom of the foot (near the heel): This is plantar fasciitis’s most common and distinctive symptom. The pain can range from a dull ache to a sharp, stabbing sensation, with some experiencing the sensation of pressing on a bruise. In addition, the arch of the foot may also feel sore or have a burning sensation.

Severe heel or foot discomfort after getting out of bed or after resting: This pain, sometimes called “first-step pain,” is often most intense in the morning or after long periods of inactivity. This happens because most people sleep or sit with their feet in a relaxed position, causing the plantar fascia to shorten and tighten. However, the pain usually eases within five to 10 minutes.

Heel or foot pain that worsens after physical activity: Pain may intensify after exercise or prolonged standing, although it usually isn’t felt as much during the activity. Climbing stairs can be particularly painful. The pain may feel more intense when walking barefoot or wearing shoes that provide little support.

Tenderness when pressing the affected area: The heel or surrounding area is often sensitive to touch, especially near the point of attachment of the plantar fascia.

Foot stiffness: Stiffness is common, particularly after waking up or sitting for extended periods. This stiffness can make walking uncomfortable or difficult at first.

Restricted dorsiflexion: Individuals with plantar fasciitis have difficulty lifting their toes and feet upward toward their shins (dorsiflexion). This limited movement can make it hard to walk normally, go upstairs, or run.

Limp: A limp may be noticeable, or there may be a tendency for a patient to walk on the toes.

Tight Achilles tendon.

An average episode of plantar heel pain lasts over six months. Heel pain from plantar fasciitis often resolves on its own but can persist for months to years despite treatment. Up to 80 percent of patients may continue to experience symptoms a year after being diagnosed.

What Causes Plantar Fasciitis?

The exact cause of plantar fasciitis is not always easy to identify. It often develops with age as the fascia loses its elasticity or when the plantar fascia ligament undergoes long-term overstretching, repetitive strain, or minor injuries over time, leading to inflammation and pain.

Several factors can cause this condition, including:

Constant stretching and strain of the plantar fascia: With each step, our body weight initially rests on the heel and then shifts across the foot. As the foot flattens under this weight, it exerts pressure on the plantar fascia, which has limited flexibility. While we walk, the plantar fascia pulls on its attachment at the heel. Continuous stretching and strain on the plantar fascia can lead to chronic degeneration, causing small tears in the fibers near the heel bone. Ultrasound also often reveals calcifications and thickening of the fascia.

Aging: With age, the plantar fascia loses elasticity, and the heel’s fat pad thins, reducing its capacity to absorb shock. This added impact can damage the fascia, causing swelling, bruising, or tears.

Gastrocnemius tightness: Another leading cause of plantar fasciitis is tightness in the gastrocnemius (a major calf muscle), which limits foot flexibility. This tightness increases the impact on the foot with each step, further stressing the plantar fascia.

Achilles tendon tightness: The Achilles tendon is the strong tissue connecting the calf muscles to the heel bone. Tightness here is also commonly linked to plantar fasciitis.

Repeated impact on the heel: Repeated impact on the heel from running, walking, standing, prolonged standing or jumping, and excessive rolling in (pronation) or rolling out (supination) of the foot can also lead to plantar fasciitis.

Existing foot arch problems: Foot arch issues, such as flat feet or high arches, can also contribute to the condition. Flat feet (pes planus) can put extra strain on the plantar fascia, while high arches (pes cavus) can lead to increased stress on the heel because the foot doesn’t absorb shock effectively.

Previously, plantar fasciitis was believed to be caused by heel spurs, but research shows this isn’t true.

Who Is at Risk of Plantar Fasciitis?

The following factors put a person at higher risk of plantar fasciitis:

Sex: A higher prevalence of plantar fasciitis was observed in females (1.19 percent) compared to males (0.47 percent) in the 2013 National Health and Wellness Survey.

Obesity: According to the same survey, the prevalence was higher in obese individuals (1.48 percent) compared to those with a body mass index (BMI) of less than 25 (0.29 percent).

Age: People aged 40 to 60 are at a higher risk.

Race: According to the 2013 survey, among different ethnic groups, Hispanic whites had the highest rate of plantar fasciitis (0.95 percent), followed closely by non-Hispanic whites (0.93 percent). Both groups had significantly higher rates compared to non-Hispanic blacks, who had a prevalence of 0.54 percent.

Running: Research indicates that the prevalence rates among runners are higher than among nonrunners, especially those who run long distances, downhill, or on uneven surfaces.

Shoes with inadequate arch support or soft soles: Flip flops are one example.

Prolonged sitting.

Prolonged standing or walking on hard surfaces: People in higher-risk occupations include nurses, teachers, chefs, and cashiers.

Long-term high-heel use.

Corticosteroid injections: Repeated corticosteroid injections may lead to degenerative changes in the fascia, a potential loss of the cushioning subcalcaneal fat pad, and an increased risk of plantar fascia rupture.

Certain conditions: Conditions such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and diabetes are associated with plantar fasciitis.

Subcalcaneal spurs.

Walking barefoot often.

Leg-length discrepancy: Having one leg shorter than the other can lead to increased stress on the fascia of the longer leg, as it bears the body’s weight for longer. Meanwhile, the foot of the shorter leg hits the ground harder, resulting in additional pressure on that foot.

Poor calf muscle flexibility.

Pregnancy: Plantar fasciitis may result from the added weight due to pregnancy.

How Is Plantar Fasciitis Diagnosed?

A physician typically diagnoses plantar fasciitis through a clinical exam. This exam may reveal pain on the bottom or sole, flat feet or high arches, mild swelling or redness, and stiffness or tightness in the foot arch or Achilles tendon. Dorsiflexion (upward flexing of the toes) often intensifies pain, which stretches the plantar fascia. Diagnosis also involves assessing the patient’s medical history and physical activity.

Imaging Tests

Since plantar fasciitis is diagnosed clinically, imaging is typically unnecessary. The imaging tests that a health provider may request include:

X-rays or ultrasound: If the health provider suspects the presence of other conditions or the patient doesn’t improve over time, X-rays or an ultrasound may be ordered to reveal these conditions, such as heel spurs and calcifications. An ultrasound may show thickening and swelling of the plantar fascia, which is common in plantar fasciitis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): If a patient doesn’t respond to extended conservative treatment, a provider may recommend an MRI to check for tears, stress fractures, or bone defects. MRI can confirm plantar fasciitis by showing thickened plantar fascia and increased signals on specific imaging sequences.

Technetium scintigraphy: Technetium scintigraphy is a type of nuclear imaging test that uses a small amount of radioactive material, typically technetium-99m, to help visualize specific areas of the body. Technetium scintigraphy can pinpoint the site of inflammation and rule out a stress fracture.

What Are Possible Complications of Plantar Fasciitis?

Possible complications of plantar fasciitis include:

Tendon or plantar fascia rupture, particularly with the use of corticosteroid injections

Tissue death of the fat pad

Loss of the arch’s natural curve

Chronic heel pain

Altered gait due to pain

Heel spurs

What Are the Treatments for Plantar Fasciitis?

Most people with plantar fasciitis do not need specific treatment, as the condition often resolves on its own. However, the following treatments may be considered.

- First-Line Treatments

The primary treatment approach is to avoid aggravating activities. The following are treatments to pursue first:

Rest from strenuous activities: Limiting athletic activities, taking shorter steps, and incorporating extra rest may help relieve symptoms. However, a complete lack of physical activity is not recommended, as it may lead to stiffness and a recurrence of pain. Elevating the feet while sitting or lying down can also help reduce swelling.

Cushioned footwear: Cushioned footwear, including prefabricated silicone heel inserts, cushion-soled shoes with gel pads, and heel cups, can help relieve plantar fasciitis symptoms by reducing heel pressure. People on concrete floors can benefit from extra cushioning. Walking barefoot or in slippers, even on carpet, can worsen symptoms, so wearing supportive shoes immediately upon waking is advised.

Walking boots and crutches: These are used for a short period.

Ice packs: Applying ice packs to the heels and arches after activity for 20 minutes, three times daily, can help reduce pain and swelling. Rolling the foot over a cold water bottle may also be effective. Those with diabetes or poor circulation should consult a doctor before using ice therapy.

- Medications

NSAIDs: A health provider may suggest a short course (two to three weeks) of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen or naproxen for pain relief. However, the benefits may be limited, and side effects are possible. Topical NSAIDs (such as creams or gels) applied to the painful area may also provide relief with fewer systemic risks.

Acetaminophen: Acetaminophen can reduce pain but with minimal anti-inflammatory effects.

- Nonsurgical Options

Deep friction massage of the arch and insertion: Friction massage is a technique that boosts circulation and releases tension, especially around joints or in areas with muscle or tendon adhesions. Massage can help alleviate pain and decrease the chances of the condition becoming chronic.

Shoe inserts or orthotics: Foot orthoses, which can be prefabricated or custom-made by orthotists, should support the medial arch and cushion the heel. Custom-made foot orthotics are devices inserted into shoes to support, align, and accommodate foot abnormalities while improving foot function. Selecting the right material for the orthotic is crucial for effectively addressing your foot condition.

Night splints: Night splints are designed to keep a gentle stretch on the plantar fascia while a person sleeps. It prevents the plantar fascia from tightening during the night, helping reduce pain and stiffness in the morning.

Casting: A short walking cast extends from the calf to the toes and has a rocker-shaped bottom for walking. It may help relieve symptoms. However, this method has not been tested in clinical trials.

Weight loss in patients with obesity.

Physical therapy: A physical therapy program may include exercises to stretch the calf muscles and plantar fascia, along with ice, massage, and other treatments to reduce inflammation.