|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

It was not really comparable to the famed Dreyfus Trial, but viewers of the film on the Goldman Trial will be left wondering if this particular anti-hero was created by centuries of European anti-Semitism.

By: Phyllis Chesler

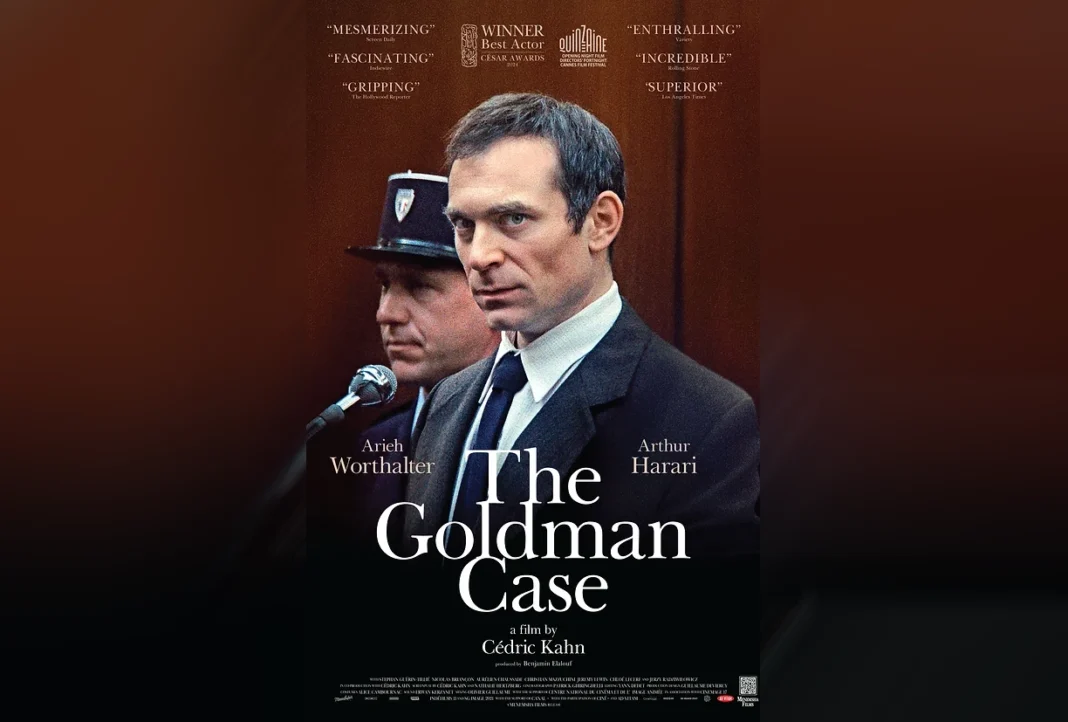

Director Cedric Kahn’s “The Goldman Case” is an intense courtroom drama which recreates a trial which took place in Amiens, France in 1976. At the time, many people viewed it as the Trial of the Century—but Goldman is no Dreyfus, whose false accusation of treason in the nineteenth century in France led to a conviction.

After the Dreyfus Trial, Emile Zola wrote “J’Accuse” condemning the conviction as anti-Semitic; assimilated, Austro-Hungarian journalist, Theodor Herzl, covered the trial, witnessed the Parisian street mobs crying out “Death to the Jews—and became a changed man. Herzl wrote “The Jewish State,” and, in 1897, convened the first-ever Zionist Congress, in Basel, Switzerland.

Goldman was not framed because he was a Jew—although he sometimes believes that is the case. Goldman insists that he is innocent, and did not commit any murders. However, Goldman is a Dostoeveskyan anti-hero, and the film compels us to ask some very difficult questions.

The film about the Goldman trial is a psychological, legal, and political thriller with enormous post-Holocaust implications for France, for Europe, and for world Jewry.

This film is difficult to watch; we are not meant to “like” Goldman—and we don’t. I didn’t. But I was riveted by the issues raised by this case,

Pierre Goldman is the son of Polish Jews who were, allegedly, “resistance” heroes in World War Two. While Goldman is aggressively, barricade-style paranoid about police corruption, police racism and police anti-Semitism, (he may be right about this), Goldman, played brilliantly by Arieh Worthalter, is himself a very impulsive, arrogant, vulgar, rageaholic, an utterly unpleasant defendant, and an impossible client, one who, at the last moment, tries to fire his lawyer, Georges Kiejman, another French, Polish-born Jew.

Goldman is the kind of Jew who is anti-religion, anti-Judaism, and anti-Zionism, an anti-racist communist who believes in violent revolution. Therefore, he becomes an icon of the Far Left in France. His book, written during his first prison term, Dim Memories of a Polish Jew Born in France, gained the support of Jean Genet, Jean-Paul Sartre, Regis Debray, and even Simone Signoret. Goldman both defends and identifies with Black Caribbeans in France.

Goldman-on-trial has the support of a very noisy, self-appointed claque in the courtroom, one that jeers, hoots, applauds, claps, and laughs, as it suits them. They, like Goldman, cannot be controlled, know no boundaries, or rather, wish to overthrow all boundaries, disrupt order, cause chaos. Like Goldman, they do not respect the judges or the lawyers and refuse to conform to expected courtroom civilities. It reminds me of similar, contemporary behaviors on Western campuses, in classrooms, and on the streets.

Admirably, the film whitewashes nothing and no one. Although Goldman is ultimately found guilty of the robberies, the jury does not find him guilty of the murders. As an aside: I find it disturbing that the film does not emphasize that the two murdered pharmacists were both women; neither are ever named.

Goldman wants to be a hero, a “Jewish warrior,” but he does not move to Israel in order to do so there; rather, he travels to South America, to Cuba, and Venezuela, where he searches for—but is too late to find Che Guevara. He is the kind of Jew who proudly rejects provincialism, tribalism, tradition, and instead embraces universalism, socialism-communism, bohemianism—and crime.

Upon Goldman’s return to France, he does not support himself by writing—but by armed robberies. He becomes a gangster, a man who drinks quite a lot, and frequents prostitutes. In the film, he admits that he is “not proud of it.”

The film allows the viewer to ask a series of questions. Is Goldman’s paranoia, rage, obsession with violence, and his absolute inability to fit into society, due to Holocaust-related trauma? The Shoah separated from his mother who remained behind in Poland and who, according to Goldman, “lived only for her ideas.” Is he forever trying to please this absent parent? Is Goldman psychiatrically, genetically, neurologically, disturbed?

He often makes no sense. He believes that being Jewish is the same as being Black. He says that “I wanted to be like my parents, a hero, that’s why I went to carry out guerilla warfare in Venezuela.” Hmmmm??

Goldman also insists that he is “innocent because he is innocent.” He does not need witnesses or facts.

Has this particular anti-hero been created by centuries of European anti-Semitism? Is Goldman their creation? Is his refusal to identify as a Jew (except to claim persecution along those exact lines), a product of the intense Jew-hatred on the European continent? Do persecuted people have no moral or legal responsibility for their actions?

Maitre Klejman, his lawyer, masterfully played by Arthur Harari, says: “One cannot understand Pierre Goldman without understanding the impact of his family’s past on his personality and struggles….to leave the ghetto there was only Zionism or Communism. That’s a fundamental aspect of Judaism, not a religious aspect, but a link with universalism, with historicity. That of the emblematic history of revolutionary Jews.”

Ghettoes, atrocities, Nazi concentration camps, do not necessarily make victims or second or third generation heirs into better people. Often, segregation, persecution and torture cripple the victims psychologically. Not everyone. But many. Are we to view Goldman in this way? I leave the question in your hands.

I want to thank Menemsha Films for distributing this gripping and timely film.

Phyllis Chesler is a prolific American writer, psychotherapist, and professor emerita of psychology and women’s studies at the College of Staten Island