|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The Altaussee Salt Mine: A Hidden Trove of Nazi Plundered Art

Edited by: TJVNews.com

In the heart of the Salzkammergut region, nestled in the Austrian Alps, lies the Altaussee salt mine, a place with a chilling history and a crucial role in the story of Nazi art plundering, as was reported on Wednesday in The Wall Street Journal. With a constant temperature of 8 degrees Celsius (46 degrees Fahrenheit) and 75% humidity, this mine became one of the most significant repositories of stolen art during World War II.

Beginning in 1943, the Nazis transformed the Altaussee salt mine into a vast storage facility for their looted art. According to the information provided in the WSJ report, The Linz Commission, tasked with amassing artworks for the Führermuseum planned for Hitler’s hometown, alongside museums throughout the Reich, collected thousands of pieces. The commission, along with the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce, which specialized in plundering cultural artifacts, stored an astounding number of works in the mine.

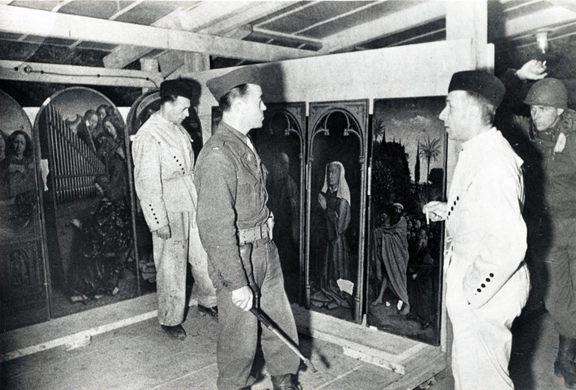

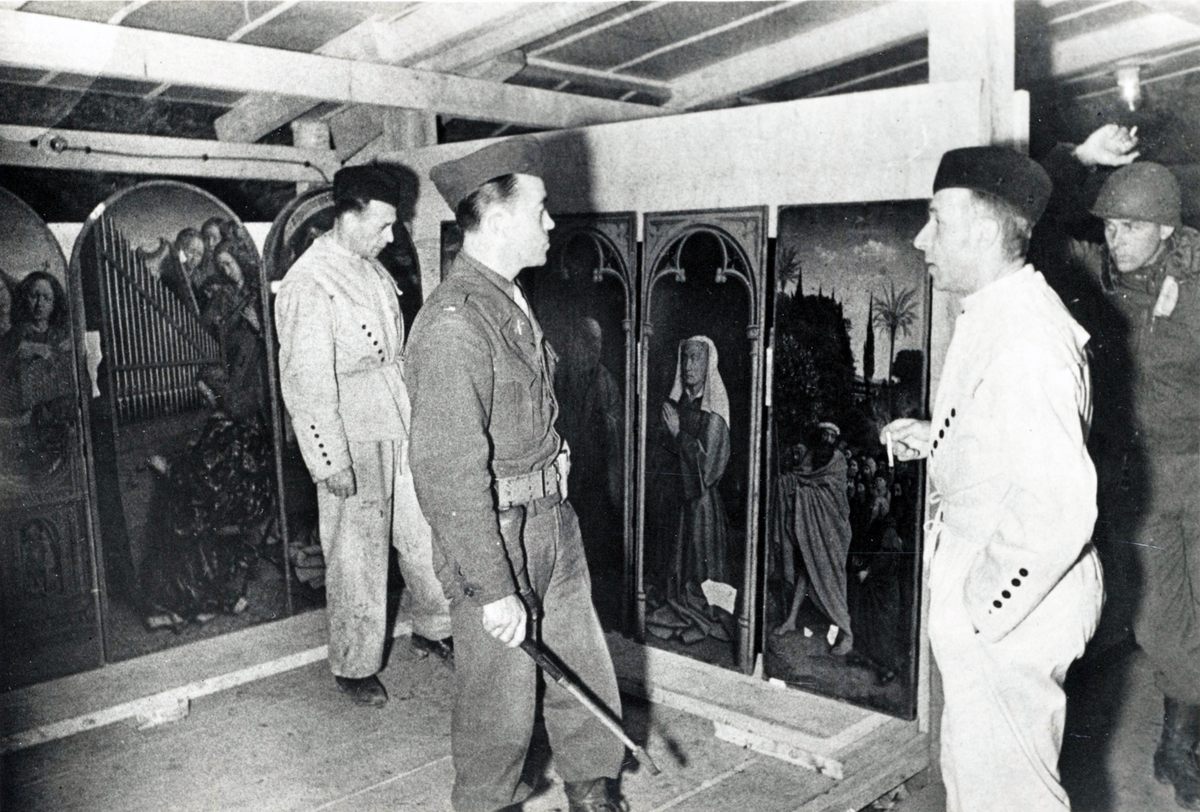

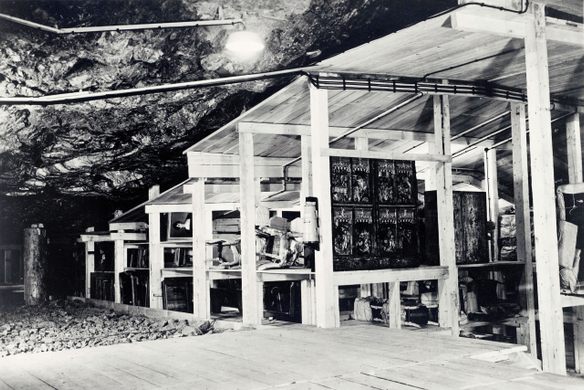

The miners constructed eight large storerooms within the mine, using approximately 42,000 cubic feet of wood. These storerooms housed 6,577 paintings, 250 drawings and watercolors, 954 prints, and 137 sculptures. Indicated in the WSJ report was that among these treasures were masterpieces like Michelangelo’s “Madonna of Bruges,” Jan van Eyck’s “Ghent Altarpiece,” and Vermeer’s “Allegory of Painting” and “The Astronomer.”

The Altaussee salt mine was chosen not only for its expansive underground chambers but also for its protective environment. The stable climate within the mine helped preserve the artworks, while the 400 feet of stone above provided a formidable shield against Allied air raids, the WSJ report explained. As the Third Reich faced destruction, these measures ensured the survival of their plundered art collection.

Altaussee was not the only site used by the Nazis for hiding their stolen art. Mines, castles, and monasteries across Germany and Austria served as secret storage locations. However, the report in the WSJ noted that the Altaussee remains the most well-known and arguably the most spectacular of these sites, symbolizing the scale and audacity of the Nazi plundering operation.

The legacy of the Altaussee salt mine and its hidden treasures is being revisited through exhibitions that shed light on this dark chapter in history. “The Journey of the Paintings,” currently on display at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, is part of a series of exhibitions in Upper Austria and Styria that explore the Nazis’ use of the Salzkammergut region for transporting and storing stolen art, the WSJ report revealed.

Although the exhibition does not include the most famous masterpieces, it does feature nearly 80 paintings and works on paper that were once kept in the Altaussee mine, as per the information contained in the WSJ report. Arriving nearly 80 years after the end of World War II, these exhibitions are more than just displays of art; they represent a momentous step in Austria’s reckoning with its past. By showcasing these works and telling their stories, the exhibitions not only honor the cultural heritage that survived but also serve as a reminder of the atrocities committed during the war.

As was stated in the WSJ report, despite its noble intentions, the exhibition falls short of being the engrossing artistic journey it promises, due to a combination of an overly broad selection of works and a problematic presentation.

Curated by Elisabeth Nowak-Thaller and Birgit Schwarz, the exhibition brings together an impressive array of artworks, from Italian Renaissance portraits and 17th-century Dutch still lifes to German Romantic paintings and 20th-century works deemed “degenerate” by the Third Reich, as was detailed in the WSJ report. This diverse collection showcases the breadth of the Nazis’ plundering activities, offering a comprehensive view of their cultural theft. However, this variety also contributes to the exhibition’s lack of cohesion.

A more focused selection of key pieces might have provided a stronger narrative and greater impact. According to the WSJ report, notable works such as the “Portrait of Guido della Torre” (c. 1505) attributed to Lorenzo Lotto, Anthony van Dyck’s “Jupiter as Satyr With Antiope” (c. 1620), Hans Makart’s “Lady at the Spinet” (1871), and early-20th-century garden scenes by Max Liebermann and Edvard Munch stand out but get lost in the broader, more scattered presentation.

The exhibition’s layout further detracts from its effectiveness. The artworks are primarily arranged along the perimeter of a large rectangular gallery, with a contemporary art installation, “Ruinenwert” (“Ruin Value”) by German artist Henrike Naumann, occupying the center. Also mentioned in the WSJ report was that this installation, intended as a “critical intervention,” disrupts the flow and focus of the exhibition, proving to be a serious misstep.

Additionally, while the provenance information provided for many works is thorough and valuable, the large placards containing extensive historical details tend to dominate the viewing experience. Visitors may find themselves spending more time reading than engaging with the art itself, as was observed in the WSJ report. This detailed scholarship might be better suited to the comprehensive German-language catalog that accompanies the exhibition.

The provenance of many artworks on display remains a sensitive issue. Notably, most of the works on loan originate from public collections in Germany and Austria. This suggests a hesitance from major institutions elsewhere in Europe to send their once-looted artworks back to the region, reflecting ongoing complexities surrounding the restitution of stolen art.

Among the few works loaned from non-German and Austrian collections are two 17th-century Dutch paintings from the Mauritshuis in The Hague: Cornelis de Man’s “Interior of the Laurenskerk in Rotterdam” (c. 1665-67) and Isack van Ostade’s “Ice Scene” (c. 1640-42), as per the WSJ report. Additionally, two canvases from France include Makart’s “Still Life With Violin” (1876) from Paris’s Musée d’Orsay and Felix Ivo Leicher’s “Martyrdom of St. Thekla” (c. 1755) from the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Tours. The prewar provenance of these works is still unknown, and placards beneath them direct viewers to the appropriate Dutch and French agencies for further information or assistance.

Among the numerous artworks on display, only two paintings that have been successfully restituted to the descendants of their prewar owners are showcased. The WSJ reported that they are Friedrich von Amerling’s “Girl With a Straw Hat” (1835), returned to the heirs of Ernst and Else Gotthilf in 2007, and Ludwig Schnorr von Carolsfeld’s “Vale of Chamonix With Mont Blanc” (1848), returned to the heirs of Josef Blauhorn in 2012, now belong to the Liechtenstein Princely Collections in Vienna.

The limited number of restituted works is disappointing, according to the WSJ, particularly given the museum’s history. Since 1998, the Lentos has returned 13 paintings to the families who owned them before the Nazi era.

A significant aspect of the exhibition is its exploration of Wolfgang Gurlitt’s legacy. Gurlitt, a Berlin-born art dealer, founded the Neue Galerie der Stadt Linz (now the Lentos Kunstmuseum) in 1953. Noted in the WSJ report was that despite his significant contributions to the art world, Gurlitt’s legacy is marred by his opportunistic activities during the Nazi regime.

Nearly bankrupt before Hitler’s rise to power, Gurlitt thrived under the Nazis by acquiring art from collectors forced into exile and obtaining at least one painting confiscated from its Jewish owner, as was explained in the WSJ report. His dealings included artworks from Jewish families, adding a layer of moral complexity to his role as an art dealer. In 1944, he relocated to a bungalow in Bad Aussee, where he continued to influence the local art scene until his death in 1965.

The Kammerhofmuseum in Bad Aussee, a spa town near Altaussee, delves deeper into Gurlitt’s controversial legacy with the exhibition “Wolfgang Gurlitt. Art Dealer and Profiteer in Bad Aussee.” Curated by Elisabeth Nowak-Thaller, this two-room exhibition features roughly 60 works from the former Gurlitt collection, on loan from the Lentos, the WSJ report said. The collection includes drawings and lithographs by renowned artists like Gustav Klimt, Oskar Kokoschka, and Egon Schiele.

The exhibition paints a nuanced picture of Gurlitt as both a champion of modern art and a ruthless opportunist. A particularly poignant mystery surrounds a Klimt painting, “Posthumous Portrait of Ria Munk III” (1917-18), which Gurlitt acquired under unclear circumstances. The painting once hung in the villa of Aranka Munk, who perished in the Łódź Ghetto in 1941. The report in the WSJ said that The Lentos returned the painting to Munk’s heirs in 2009, highlighting the continuing efforts to rectify historical wrongs.

In 2019, the Springerwerk, a 3,000-square-foot depot within the Altaussee mine, was restored to host a small yet poignant exhibition titled “The Fortune of Art.” This site once sheltered masterpieces like the Ghent Altarpiece and paintings by Vermeer, Bruegel, and Rembrandt. Noted in the WSJ report was that although the current exhibition features copies of these iconic works, it also includes two original New Testament scenes painted around 1800. These canvases were presented to the Altaussee miners by the Vienna Institute for the Protection of Monuments, honoring their critical role in safeguarding the artworks during the war.

As World War II drew to a close in April 1945, the mine faced a dire threat. August Eigruber, the local Gauleiter, delivered eight 1,100-pound bombs disguised in crates marked “Caution: Marble, Do Not Drop.” His plan was to destroy the mine to prevent it from falling into Allied hands. However, the WSJ report indicated that Emmerich Pöchmüller, the general director of Altaussee mining operations, courageously thwarted this plan. In early May, Pöchmüller’s miners removed the bombs and sealed the mine’s entrance with a controlled explosion, preserving the priceless treasures within.

Two weeks later, American soldiers Robert Posey and Lincoln Kirstein, members of the Monuments Men, located the blown-up entrance and ventured inside. Their mission was to recover the looted artworks and transport them to the Central Collecting Point in Munich, some 150 miles away. This marked the beginning of a painstaking process to match the artworks with their prewar owners, ensuring their return to rightful heirs and institutions, as was reported by the WSJ,

Today, the cool storerooms and tunnels of the Altaussee mine serve as a vivid reminder of history’s greatest art theft and the remarkable efforts to preserve cultural heritage. Visitors to “The Journey of the Paintings” exhibition can see many works that once found refuge in the mine, bringing to life the harrowing close call that nearly saw the loss of humanity’s greatest artistic achievements.

The Altaussee salt mine stands as a symbol of resilience and dedication to cultural preservation. Its storied past, intertwined with the fate of priceless artworks, offers a profound narrative of courage, ingenuity, and the enduring power of art to transcend the darkest periods of human history.