|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Sara Miller

A random observation by an Israeli cognitive neurologist about the demographics of Jews with early onset of Alzheimer’s disease has led to a genetic study with the potential to shake up how we diagnose and treat patients suffering from this condition.

The World Health Organization says Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia, with around 40 million sufferers worldwide in 2023. There is no cure for or even a universally accepted cause of the disease, despite it being first diagnosed more than a century ago.

In 2017, Dr. Amir Glik, the director of Cognitive Neurology at Beilinson Hospital, realized that of his Jewish patients experiencing cognitive decline, well over half were Sephardi Jews – those who originate from Spain and Portugal in Southern Europe and later North Africa and the Middle East.

“I started asking myself, why does it happen?” Glik tells NoCamels. “Whether my feeling is something that I can prove with statistical methods or is it just a feeling.”

Glik and his team then began to go through hundreds of patient files at the hospital’s cognitive neurology clinic, some dating back years, to see whether there were statistics to back up this intuition.

“After doing the work, examining hundreds of patients, we saw that this is correct,” Glik says.

What they found was that 64 percent of the Jewish patients with early onset dementia were Sephardi, as compared to 36 percent Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern and Northern Europe.

The team then went to Israel’s Health Ministry and other government bodies to acquire annually updated data, which also bore out the trend that they had uncovered at Beilinson.

Glik stresses that the study relates to people aged around 60, who are below the average age for Alzheimer’s diagnosis but older than those who have genetic inclination to develop the disease in their 40s.

According to Glik, Israel’s relatively homogeneous population makes it easier to identify genetic trends within certain ethnic groups and then expand any findings out to more diverse communities.

“The idea when you do a genetic study is to take a population that is a closed population,” he says. “[And] people who studied genetics said that Israel is heaven from a genetical standpoint.”

Glik explains that in a closed population such as Israel, less diversity means there will be a higher percentage of the population with certain genetic risk factors, making them easier to locate.

“In order to find a genetic risk factor in a homogenic population like the Ashkenazi Jews, or like the [Sephardi] Jews, you need a much lower number of participants in order to find the genetic risk factors,” he says.

He gives the example of the Israeli research that discovered that Ashkenazi Jewish women are more genetically disposed to developing breast cancer. This is because one in every 40 Ashkenazi Jewish women has a mutation of the BRCA gene, something which increases the risk of developing breast cancer and ovarian cancer at a young age. Conversely, only one in every 140 Sephardi Jewish women has the gene mutation.

Once identified, Glik says, these risk factors can then be examined in more heterogenic populations such as in the United States or Europe.

Glik maintains that in the past few years there has been a subtle “revolution” going on in the study of Alzheimer’s disease, unbeknown to most people.

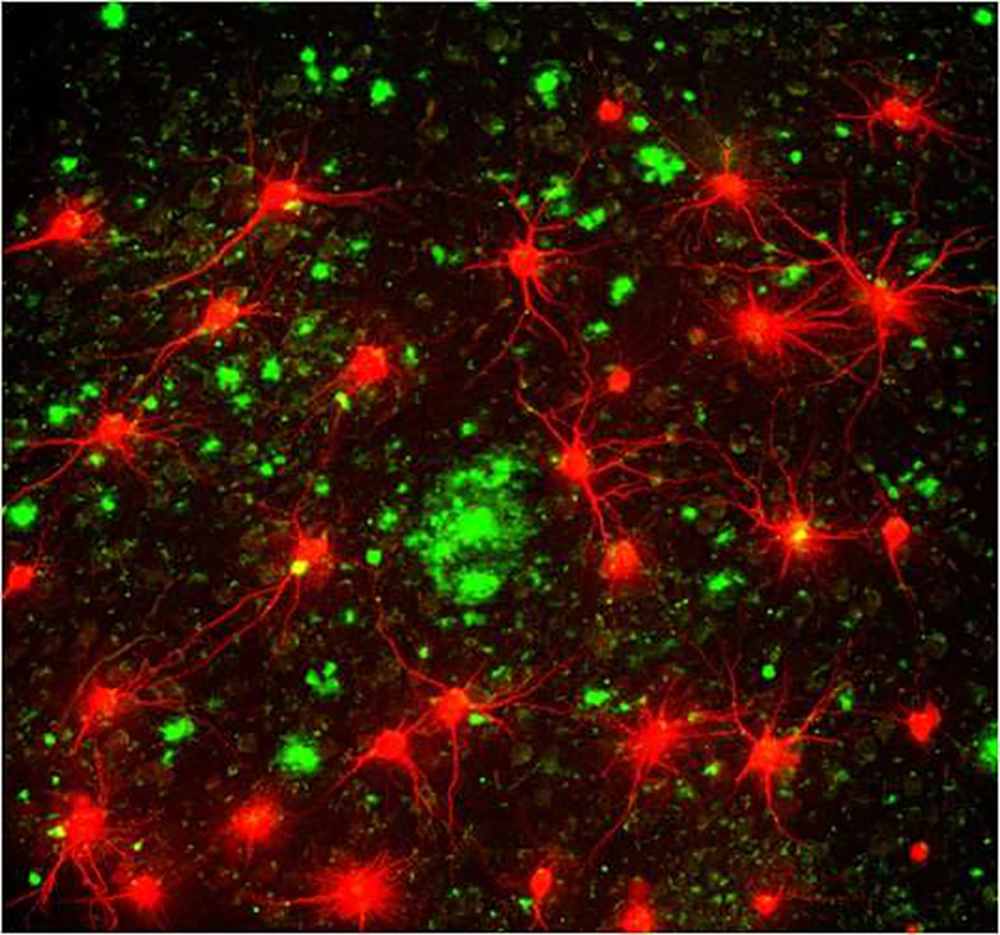

He highlights the introduction of two new drugs to “clean” the build up of the Amyloid beta protein in the brain, which is thought to be one of the primary factors in the development of Alzheimer’s. A third new drug is expected to receive approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the summer.

“What happened in psychiatry 20, 30 years ago is now happening in Alzheimer’s disease” Glik says.

Indeed, the Beilinson study has drawn attention from the US government. Its National Institute of Health has provided $13 million to expand Glik’s genetic research into a joint study with Boston University School of Medicine and three other Israeli medical centers.

The hope is that this will help advance early detection, treatment and care for sufferers of the disease.

“We want to know what are the mechanisms that cause Alzheimer’s disease,” Glik says.

“If we know the genes that are risk factors for the disease, then we can learn about the mechanisms of the disease and maybe find a drug that can interfere in this mechanism, and postpone disease development. That’s the aim.”