|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

After three days of electrical stimulation, 47 percent of patients reported improvements in loudness, and 36 percent reported improvement in severity.

By: Megan Redshaw, J.D.

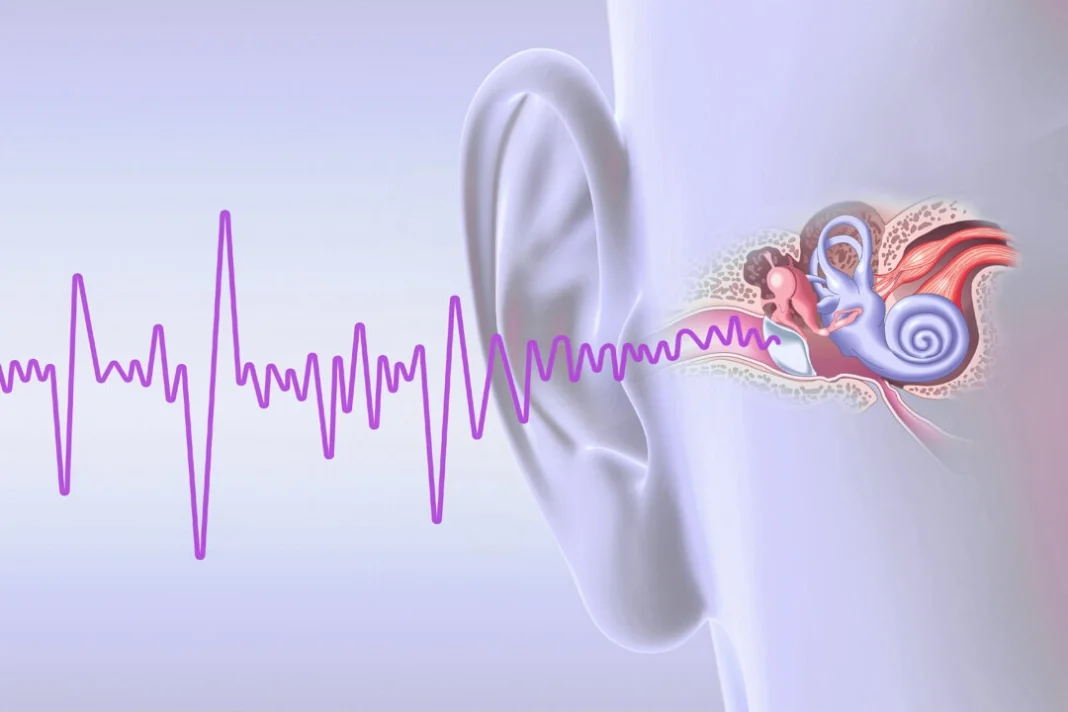

A therapeutic, noninvasive therapy may bring relief to millions of Americans suffering from tinnitus, a debilitating condition with no approved pharmacological treatment or cure.

In a proof-of-concept study recently published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine, researchers found that electrical stimulation through the ear canal decreased loudness and tinnitus-induced distress in just three days, especially for women and those with tinnitus affecting both ears.

Using an electrode placed in the ear, 66 patients underwent 10 minutes of electrical stimulation for three days while researchers monitored how it affected their symptoms. They analyzed several factors, including the frequency of the stimulation current, the sequence of applying different currents, the severity of tinnitus at admission, whether tinnitus affected one or both ears, sex, and age of the patients.

Of the 66 patients, 47 percent experienced a statistically significant reduction in tinnitus loudness, and 36 percent reported improvements in symptom severity. Moreover, women reported reduced tinnitus loudness immediately after the first ear stimulation session and after subsequent sessions, whereas men didn’t respond positively until after the second and third sessions. The researchers said gender differences in sensory reactivity could explain why women responded sooner and more positively, as women are more sensitive to electrical stimulation.

In patients with tinnitus affecting both ears, symptoms responded more favorably to earlier treatments than those with tinnitus affecting only one ear. Age had no affect on the success of the treatment.

Finally, the study showed that patients with compensated/habituated tinnitus responded differently to electrical stimulation than those with decompensated/unhabituated tinnitus.

According to a paper published in Brain and Behavior, decompensated/unhabituated tinnitus is a “complex psychosomatic process” in which a person experiences considerable suffering from tinnitus and does not become accustomed to it. This sometimes leads to psychological symptoms such as difficulty falling asleep, insomnia, aggression, difficulty concentrating, anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts. Those with compensated/habituated tinnitus hear phantom sounds but become accustomed to them.

The researchers found that patients with both types of tinnitus experienced “significantly reduced loudness” after the second and third electrical stimulation sessions, but only those with compensated/habituated tinnitus experienced a significant reduction in distress after three days of treatment.

What Is Tinnitus?

Tinnitus is a perception of sound without an external source, meaning it’s a sound other people cannot hear. The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders estimates that 10 to 25 percent of U.S. adults experience some form of tinnitus—making it one of the country’s most common health conditions.

Although it is commonly described as “ringing in the ears,” people with tinnitus may hear roaring, whooshing, hissing, humming, or buzzing in one ear or both, and the noise can be soft or loud, low- or high-pitched, and sporadic or continuously present. These phantom sounds aren’t actually caused by the ear, but are generated by the part of the brain that processes sound called the auditory cortex.

Tinnitus symptoms can resolve suddenly or become chronic, which may lead to other symptoms such as sleep deprivation, difficulty concentrating, psychological distress, and depression.

Some research suggests tinnitus is caused by damage to the inner ear that changes the signals carried by the nerves to the auditory cortex, while other evidence suggests that abnormal interactions between the auditory cortex and neural circuits could contribute to the condition.

Tinnitus can also be caused by other conditions such as Ménière’s disease, diabetes, autoimmune conditions, heavy metal toxicity, tumors, jaw problems, noise exposure, hearing loss, and medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen and aspirin, certain antibiotics, anti-cancer drugs, antidepressants, and vaccinations.

For example, according to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, more than 26,000 people have reported developing tinnitus after receiving a COVID-19 vaccine.

Dr. Gregory Poland, director of Mayo Clinic’s Vaccine Research Group and editor-in-chief of the journal Vaccine, developed “unrelenting” tinnitus after receiving his second dose of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine in early 2021 and says it feels like someone “suddenly blew a dog whistle” in his ear.

In an interview with MedPage Today, Dr. Poland said he believes tens of thousands of people in the United States alone and potentially millions worldwide are struggling with the condition and that more needs to be done to determine the cause and the relief.

“What has been heartbreaking about this, as a seasoned physician, are the emails I get from people that this has affected their life so badly, they have told me they are going to take their own life,” Dr. Poland said.

Other Potential Treatments for Tinnitus

In addition to electrical stimulation, other therapeutic treatments may benefit those experiencing tinnitus, including infrared light therapy, Korean red ginseng, ginkgo biloba, zinc, melatonin, and dietary therapy.

In addition, numerous studies have found that cochlear implants may effectively reduce tinnitus. A cochlear implant is a small electronic device that provides a “sense of sound” to those who cannot hear or are hard of hearing. However, it does not restore hearing.

The authors of the proof-of-concept study suggest their research could be used to develop an extracochlear implant for tinnitus patients that could be used regardless of the degree of hearing loss.

Study Limitations

Although the study may provide hope for people experiencing tinnitus, the authors said their research has several limitations: First, the sample size was relatively small due to limited patient access during the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, there was no control group. Finally, there was insufficient audiometric information on matched tinnitus loudness and frequency and on psychological conditions that could affect the treatments.

The authors said they do not know how long the therapy’s benefits last, but their research could help future studies or be used to create a blueprint for a device that could help tinnitus patients in the near future.