|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Phyllis Chesler

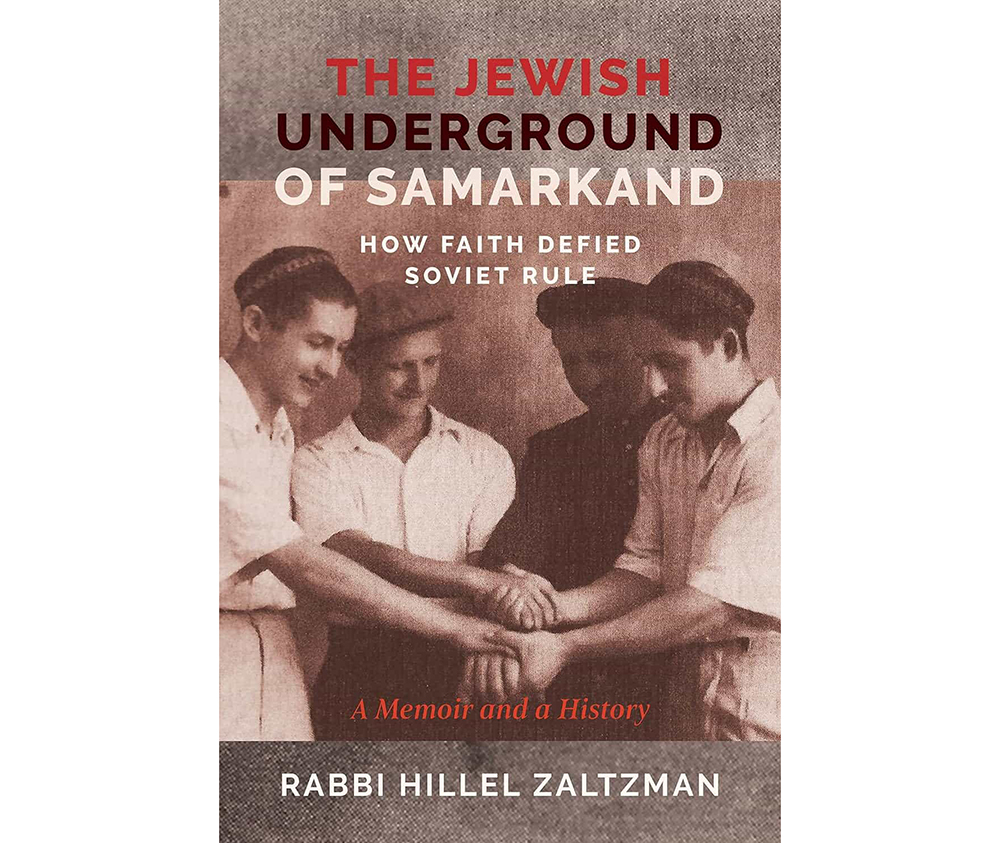

Rabbi Hillel Zaltzman has written a remarkable and very moving memoir titled: The Jewish Underground of Samarkand: How Faith Defied Soviet Rule.

Reading this is a bit like reading Chaim Grade’s My Mother’s Sabbath Days. It is filled with chaimishe details, a veritable cholent of characters, an inspiring tale of religious Jewish heroes and heroines. Zaltzman is modest; he credits and names nearly everyone who made a difference—the rabbis, their wives and daughters—and especially, their hidden yeshivah students, most of whom became major Chabad rabbis both in Israel and the United States.

After escaping from Hitler’s clutches, these Jews survived, and miraculously, even flourished all throughout Stalin’s long reign of terror and beyond that, until 1971.

Of course: Stalin starved millions of non-Jews, purged millions more and terrorized an entire country. This is the story of how the Jewish people managed to survive this murderous and anti-Semitic totalitarian regime.

Chabad Jews risked torture, exile and death daily, hourly, in order to hide other religious Jews on the run and, even more importantly, to secretly teach Torah and Yiddishkeit to Jewish youth. To do so was forbidden by Joseph Stalin himself.

The Soviet regime considered religious Jews to be “enemies of the state,” “counter-revolutionaries,” traitors, rebels and heretics; they arrested, interrogated and punished them accordingly. Informers were everywhere.

In Samarkand, little Jewish children who were chosen as Torah pupils had to be able to keep secrets. They could not tell their parents where they were spending their time. Neighbors, even Jewish neighbors, especially Jewish neighbors, had to be kept in the dark. Who knew who would crack under torture? Who was already a paid KGB informant? Then there was this horror:

“A special bureau was created for the sole purpose of stamping out Judaism, the Yevreskaya Sektzia, or Yevsektzia for short. This bureau was staffed by young Jewish men and women who had dedicated their lives to fighting religion and harassing religious Jewish and closing down their institutions.”

I hesitate to draw an analogy to our times, but you are free to do so.

The Yevsektzia was known as the Jewish section of the Communist Party. Their members took the lead in the “propaganda war against Jewish religion from 1918 until the section was disbanded in 1930.” They were directly responsible for the torture, murder, imprisonment and exile to the Gulag of major Jewish rabbis and their followers.

According to R. Zaltzman, the cantor of Leningrad’s Grand Choral Synagogue was a known KGB informant. In 1968, he was Rabbi Yehuda Leib Levin’s (the official chief rabbi of the Soviet Union), “minder, sent to keep a close eye on Rabbi Levin’s movements. Even when Rabbi Levin went to New York for a private audience with the Rebbe (at 770 Eastern Parkway), he couldn’t leave his minder outside.”

I fear that I cannot properly convey the level of chesed, self-sacrifice and kindness that one Chabadnik showed another. Food from one’s own undernourished mouth was literally given away to starving others. Tzedakah was not only a mitzvah, it was also a joy and kept a growing community alive. They starved rather than eat non-kosher food. They went to extraordinary lengths to keep Shabbat, and they found extraordinary ways to hide their religious observances.

These Jews of faith lived—and flourished—under the most primitive conditions. In one instance, a 10-foot room housed an adult couple, a newborn, and during learning hours, as many pupils as came to learn. There was no electricity, no heating; communal prayer had to be managed in secret; mikvah’s (Jewish ritual baths) had to be hidden under kitchen floors.

When no mikvah safely existed, frail and ancient Jews walked across fields of snow and ice for miles in order to immerse themselves in freezing rivers, usually before dawn.

One couple lived in a small home with a single bedroom, a kitchen and a dining room. “Still, my aunt and uncle provided for her every need as if she were a member of the family.” And who was she? A widow, abandoned by her son and daughter-in-law, and who stood at the entrance to the shul, shivering and begging.

Some Jews recited tehillim (“psalms”), by heart three times a day. Many took hours to recite the Shemah, focusing emotionally on each word, weeping as they recited prayers fervently, reverently.

Oh, I am a mighty sinner and can barely breathe the air at the altitude of their piety, charity and chesed, “deeds of human kindness.”

Persecution and danger were omnipresent. Beatings and arrests took place on the street and on trains. “It was not unusual to awake in the morning and discover the skeletal bodies of Jews strewn on the road or in the local hospital.”

But miracles abounded. Here’s just one.

The author’s father was verbally and physically attacked as a “filthy Jew” on a train. He feared the end was in sight when all of a sudden a huge man (“a giant”) came to his rescue and threw the hoodlum out of the high-speed train. And then, the “giant” calmed my father down and whispered into his ear: “You should know that I am a ger tzedek—a convert.”

Chabad rabbis rarely committed anything to paper. When they absolutely had to do so, it was always in Russian and in code. Torah scholars and their wives knew how to “unpack” Torah-related allusions as only the most Mandarin academics can do today.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson—was referred to as Zaide, “grandfather,” and Chamah—Chabad’s organization in Samarkand—was called ‘Nechama.” Zaide wanted to know whether Aunt Nechama needed helpers.

We learn only a little about Chabad’s women. (The King’s Daughter remains within). What we do learn attests to their piety and commitment to do everything that they, as women, as wives, as mothers, could do to preserve the sanctity of Torah learning and the dignity of the revered rebbes.

Many Chabad wives waited for a decade to hear from or even about husbands who had been forced to flee or who had been sent to the gulag. They refused to consider a divorce.

These women viewed their separate roles as sacred and their duties as prayers. No, I could not have done so. I would have wanted to be in one of the secret yeshivot learning, learning, but would that have necessarily kept a community intact and Judaism flourishing?

Many continue to wrestle with this question to this very day.