|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

When the Sixth Rebbe was arrested, Latvian MP Mordechai Dubin took action

By: Dovid Margolin

Just after midnight on Wednesday, June 15, 1927, agents of the Soviet secret police, then known as the OGPU, barged into the Leningrad apartment of the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory, and arrested him.

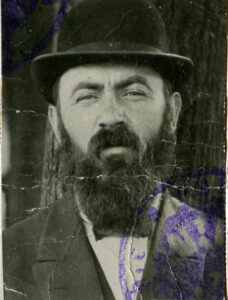

Over the next trying months, many individuals, both Jewish and not, would play important parts in obtaining the Rebbe’s freedom. One man, however, stands out: Mordechai Dubin. An influential Jewish community leader in the then-independent Baltic state of Latvia, Dubin was the Rosh Hakahal of the Riga Jewish Community and an elected representative in every sitting of the country’s parliament, the Saiema, until its dissolution in 1934.

Before that, he’d been a member of Latvia’s provisional National Council and interim Constituent Assembly. Dubin, a dedicated and pious Chabad-Lubavitch Chassid who was known for praying at length every Shabbat, combined the roles of old-world Jewish intercessor, or shtadlan, and savvy modern politician. Interestingly, he led the Agudas Yisrael political party in Latvia, though Chabad had formally withdrawn from the worldwide Agudah organization in 1909. While elsewhere in Europe the Orthodox Agudah represented the interests of its natural constituency, i.e. Charedi Jewry, Latvia had few Charedi Jews. Nevertheless, it was the most popular Jewish political party in Latvia, voted for regularly by Jews of all backgrounds, including non-observant ones. The reason was not the party, but the man who led it in Latvia: Dubin.

Dubin was beloved precisely because he “made no distinction between one Jew and another, treated them all as equals and was not concerned whether the man he helped had voted for him or not. He would do his best to free a young Jew arrested for illegal Communist activities, just as he saw to it that Jewish soldiers should be given leave for Jewish festivals. He would try to obtain a permit for a flax merchant, demand government support for synagogues or Yeshivot, or would vote in the [Saeima] for a government grant to the Jewish Theatre.”1

On June 2, 1927, Latvia signed a trade deal with the Soviet Union. Though economically Latvia needed this deal much more than the Russians did, the Bolsheviks had their own reasons for seeing the deal through. Yet, due to well-founded fears of Soviet encroachment on Latvia—after all, the country had been a Russian territory for some 150 years prior to the Revolution—there was strong internal Latvian opposition to the deal, and it still needed to be ratified by the Saiema. Dubin’s party at that point held two seats in parliament. When the Rebbe was arrested less than two weeks later, the 38-year-old Dubin found himself in prime position to play hardball with the Soviets.

“Mordechai Dubin was so strong a believer that he could not see the circumstances around the ratification of the trade agreement as anything but heaven-sent,” wrote Avraham Godin, who beginning in 1929 served as one of Dubin’s secretaries. “The timing was perfect.”2

That spring, summer and fall of 1927, a whirlwind of international events would collide, all of them seemingly in the natural order of things, but each playing a concrete role in what would culminate in a miraculous conclusion.

Religious Repression and Resistance

War on religion had been a central plank of Bolshevik ideology from the start. While Karl Marx famously declared religion “the opium of the masses,” Vladimir Lenin’s attitude was, writes Robert Conquest, “far harsher and more hostile.” For him, there was no greater threat to the Communist ideal than the rulership of G‑d. “Millions of sins, filthy deeds, acts of violence and physical contagions … are far less dangerous than the subtle, spiritual idea of a [G‑d] … ,” Lenin wrote. Absolute standards of ethics, rooted in the belief in G‑d, were incompatible with Lenin’s definition of morality as “that which serves to destroy the old exploiting class.”3

Having taken power of Russia through revolution and civil war, the new Bolshevik regime set out to destroy faith in anything other than Man. Through indoctrination, social and material pressure, physical intimidation and brute violence, they decimated religious life in the Soviet Union. No one waged this crusade more zealously than the Yevsektzia, the Jewish sections of the Communist Party, who felt the need to prove themselves “the right kind of Jews.”4 As the Yevsektzia leader Esther Frumkina explained: “The danger is that the masses may think that Judaism is exempt from anti-religious propaganda and, therefore, it rests with the Jewish Communists to be even more ruthless with rabbis than non-Jewish Communists are with priests.”5 One non-Jewish Communist admiringly remarked: “It would be nice to see the Russian Communists tear into the monasteries and holy days as the Jewish Communists do to Yom Kippur.”6

Yet traditional Judaism did have something else going for it as well—defiance. “The most tenacious, and perhaps most effective, resistance to the revolution on the Jewish street was offered by the Jewish religious community,” observed the historian Zvi Gitelman. And the undisputed leader of this resistance was the Sixth Rebbe of Chabad, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn.7

Eschewing every opportunity and invitation to leave Russia, the Rebbe—the foremost Jewish leader to remain in the USSR—threw himself heart and soul into the work of strengthening Jewish life throughout the vast empire. He did this in an organized and systematic manner, mobilizing the students and graduates of Tomchei Temimim, the yeshivah his father and predecessor had established in 1897, to take up posts as rabbis, shochetim and teachers in Jewish communities large and small. Jewish education, he knew, was of the greatest importance, and he established a wide network of clandestine yeshivahs for both young children and older students.8

For this he earned the admiration of Jews at home and abroad, but also the enmity of the Bolsheviks, and the Yevsektzia, in particular. In 1924, authorities forced the Rebbe to relocate from his base in the southern city of Rostov-on-Don to Leningrad, where they could keep a closer eye on him. On his arrival, however, they were frustrated to see a reinvigoration of traditional Jewish life in the city. An indignant Leningradskaya Pravda reported in May of 1927 that the growing interest in Judaism instigated by Schneersohn could be seen “not only among Jewish bourgeois elements, but in more or less broad circles of the Jewish working class.”9

One month later, the Rebbe was arrested.

Communist Paranoia and International Unrest

By 1927, the Bolsheviks were firmly in power, and Stalin had all but established himself as Lenin’s unrivaled heir. The issue he now faced was governing, which required a different set of skills than revolution. “Almost all the problems,” writes Stalin biographer Stephen Kotkin, “could be traced to the source of the regime’s strength: Communism.” It might be good Communist theory to tell the world that your goal was not only revolution in your country but theirs as well, but it did not bode well for international relations. Neither did Marxist-Leninist economics work as well in practice as it appeared on paper. “The problems of the revolution brought out the paranoia in Stalin,” writes Kotkin, “and Stalin brought out the paranoia inherent in the revolution. The years 1926-27 saw a qualitative mutual intensification of each…”10

Communism is inherently paranoid because it perceives enemies trying to crush the revolution everywhere.11 That the capitalist enemies of the revolution were working in concert to encircle and destroy the nascent Soviet Union was for Stalin not a cynical talking point, but a deeply held, orthodox Marxist-Leninist belief.12 That there were domestic opponents working hand-in-hand with these external enemies was also a given.13 In the winter of 1926-27 rumors ricocheted through Moscow that the Western capitalist powers were preparing some kind of attack, possibly even war. “ … [T]he OGPU reported [such a war] could take the form of an allied Polish-Romanian aggression, provoked into attack and supported by Britain and France, which would likely draw in Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, and Finland … .”14

Everybody was suspect, but Great Britain was the subject of Stalin’s greatest preoccupation. His fears were reinforced when, on May 12, 1927, British police launched a four-day raid of the offices of the All-Russia Cooperative Society in London, which operated out of the same building as the official Soviet trade mission. The British accused Soviet trading agents of abusing “their extraterritorial rights and diplomatic immunity by interfering with British domestic affairs.”15 On May 27, the British stunned Stalin by cutting off diplomatic relations with the USSR, a heavy blow especially considering Great Britain had become one of their biggest trade partners.16

A little more than a week later, on June 7, a White Russian emigre terror cell successfully detonated a bomb in Leningrad, wounding 25 and killing one. That same day, the Soviet minister to Poland, Pyotr Voikov, was assassinated on a train platform in Warsaw; he had gone there to see off diplomats expelled from the Soviet embassy in London who were en route back to Moscow. Responding to Voikov’s murder, Stalin wrote “I feel the hand of England.” On June 8, Kotkin notes, “the OGPU received additional extrajudicial powers, including the reintroduction of emergency tribunals, known as troikas, to expedite cases … .” Arrests and executions on a scale unseen since the Civil War’s Red Terror immediately followed, including sweeps of alleged “terrorist-White Guards” in Leningrad.17

Taking advantage of this frenzy of murderous paranoia, the Yevsektzia goaded the OGPU into arresting Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak. Years later, in 1965, his son-in-law and successor, the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, recalled: “The arrest took place during a time of great emergency, for that’s when the Russian ambassador was killed in Poland. The government therefore determined it would kill a certain number of their subjects.”18 This state of heightened retaliatory repression, the Rebbe noted, continued through Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s first days of imprisonment.19

The Initial Rescue Campaign

In the first 24 hours after the arrest20 emergency rescue committees were established in both Leningrad and Moscow, each consisting of leading Jewish community figures. On Thursday afternoon Rabbi Shmaryahu Gourarie, the Sixth Rebbe’s elder son-in-law, was dispatched to Moscow to bring an in-person update from Leningrad. At the subsequent meeting three courses of action to bring about the Rebbe’s release were outlined: 1. Utilize private contacts within the Leningrad OGPU. 2. Turn directly to Soviet leadership at the Kremlin. 3. Arouse the support of world Jewry and international public opinion.

As a result of the new emergency situation, Stalin had just granted extraordinary powers to the OGPU and was encouraging them to use them. At that moment the Leningrad OGPU, at the center of the broader crackdown, held the Rebbe in their hands, so the decision was made to make appeals in Leningrad on the local level and not go over their heads by turning to their bosses in Moscow. By the end of the week, however, news leaked out that the Leningrad OGPU was determined to execute Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak. On Shabbat morning, June 18, the Leningrad committee sent a messenger to Moscow relaying the dire news. At this point it was decided there was nothing to lose and it was necessary to appeal to higher Soviet authorities in Moscow.21

Urgent telegrams were immediately sent to the Kremlin. “On the fifteenth of June was arrested in Leningrad on orders of the L[eningrad]OGPU Rabbi Schneersohn,” read the Moscow committee’s urgent telegram to Mikhail Kalinin, the head of state. “Rabbi Schneersohn is deeply revered among many tens of thousands of Jews of the USSR.” Noting that the Rebbe had nothing to do with political activity, the committee asked in the name of the Moscow Jewish community that the Rebbe be released as soon as possible.22

At the same time, they sent word of the Rebbe’s arrest to major Jewish communities around the country, hoping in this way to amass hundreds of thousands of signatures for a petition protesting the Rebbe’s imprisonment. A public fast on the following Monday and Thursday was announced. One of the most consequential steps the Moscow committee took was to enlist the aid of Madame Yekaterina Peshkova, head of the Political Red Cross in Russia and the first wife of Russian literary icon Maxim Gorky. At various points Peshkova personally met with Vyacheslav Menzhinsky, head of the central OGPU, and Premier Alexei Rykov. At this point the outside world still did not know of the Rebbe’s arrest, and it seems that it was primarily due to Peshkova’s lobbying in those first few days that the Rebbe’s death sentence was stayed.23

International Mobilization

News of the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s arrest in the Soviet Union was not widely known in the West until the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA) reported it on June 28, 1927—the 28th of Sivan24 —nearly two weeks after the arrest. “The famous Lubowitscher Rebbe, Schneursohn … holds a position of high regard and esteem,” the JTA dispatch read. “His arrest has caused great excitement among the Jewish population.”25 It likewise shocked Jews around the world. “Grave news received,” Chief Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook of the Holy Land cabled from Jerusalem to the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) in New York. “Rabbi Schneirson of Lubovitch arrested Leningrad … . Try utmost for deliveration wire results.”26

To be continued next week