One year after the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, American Jewish communities are carrying on with the work of assuring a successful stay for immigrants to the country.

By: Mike Wagenheim

The grandson of Holocaust survivors, saved by Righteous Gentiles—non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews—saw the plight of Afghans fleeing for shelter and couldn’t look away.

Jonathan Kantor of Greenwich, Conn., helped lead a volunteer circle in his Jewish community to resettle Afghan refugees. His own grandparents, who were saved from the Nazis, relocated to the United States and later sheltered refugees from the Soviet Union in their home. Kantor, in turn, welcomed two Afghan brothers into his home, supported their integration, and helped them find housing and employment.

“I don’t care what religion you are. It doesn’t matter what religion I am. We’re all human beings. If you need help, I’m going to help you,” Kantor told JNS. “Twenty years from now, when you’re [the Afghan refugees] successful and you have your own business, I hope that you can do the same for other people who are coming to this country.”

Earlier this year, the Jewish Federations of North America (JFNA) partnered with the Shapiro Foundation in a $1 million initiative to support local Jewish organizations in resettlement efforts for more than 1,900 Afghan refugees across 15 communities and 12 states, as well as through 42 volunteer circles.

The grants enabled Jewish communities to develop a program to match their unique needs, including hiring a full or part-time volunteer coordinator and utilizing funds to provide direct support to evacuees. Kantor volunteered through Jewish Family Services of Greenwich, working in conjunction with UJA-JCC Greenwich.

The brothers welcomed by Kantor are now living in Stamford, Conn., after he helped them find jobs. He said while they were living nearby, Kantor drove them to work each night during the winter, and the brothers spent snow days playing with Kantor’s two little boys.

“I just had breakfast with them last week. They’re much more self-sufficient than they were when they first arrived. Their English skills are improving. They’re like little brothers for me, and they’re always going to be a part of my family,” said Kantor.

The three took a walk one day when the brothers asked whether Kantor worked for Jewish Family Services. When Kantor replied he did not, the brothers asked why he was helping them.

Kantor thought it was important, so he used a phone application called Tarjimly, which connected Kantor with a translator fluent in English and Dari. Kantor relayed to the brothers the story of his grandparents.

“It was eye-opening for them, and they understood immediately why I was doing this, and over time, they shared their stories as well,” he said.

‘An honor to their legacy’

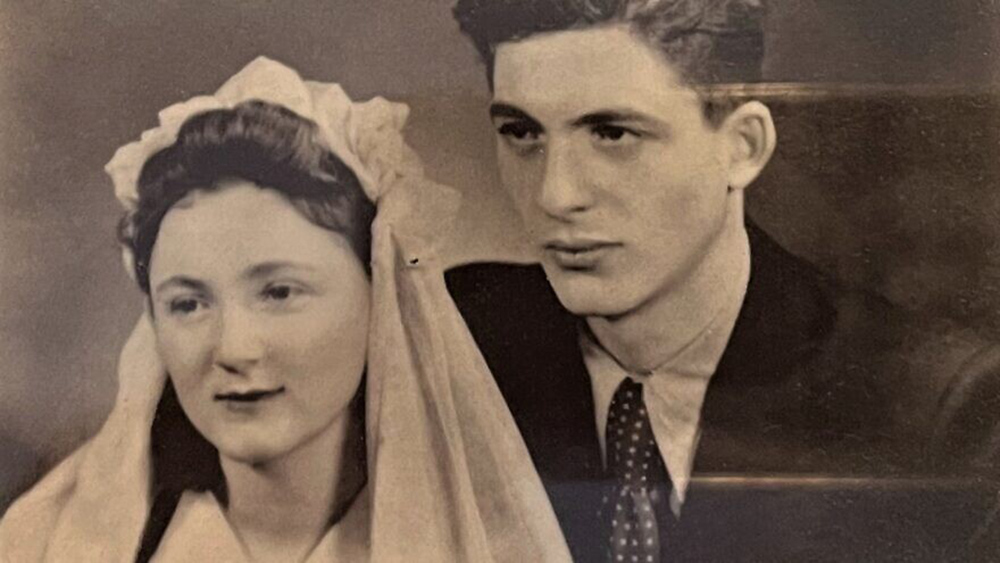

Kantor’s grandfather Irving Sklaver, aged 17, fled the small town of Hosht, then part of Poland, along with his two brothers, during World War II. As they rode their bicycles across Russia, one of Irving’s brothers was caught and killed, while another was sent to a labor camp in Siberia.

Irving made it to Uzbekistan, where he was taken in by a community of non-Jews who fed him and made sure he had places to stay, according to Kantor.

His grandmother Sonia, who grew up in the same town as Irving, survived the Nazi occupation.

She missed a roundup of Jews; her mother and sister were shot in their home. To survive, Sonia pretended not to be Jewish and, at the age of 13, secured work as a nanny. According to Kantor, Sonia would take the children under her watch out to play and could see roundups of Jews and hear gunshots.

“She was in hiding, but at some point during her tenure with this family, she wasn’t eating meat, and the grandmother suspected she was Jewish. So she forced her to go to a priest and confess her sins,” said Kantor. “My grandmother went to the priest and told him everything. She said, ‘I’m Jewish, I’m hiding, I have no family left.’ ”

According to Kantor, the priest gave her a cross to wear around her neck and said, “Your secret is safe with me. I won’t tell a soul. You go back to the family and tell them that you’re not Jewish, and you stay safe.”

When the war was over, Irving returned home and looked at a registry to see who survived. It was just a handful of people, including Sonia.

“My grandfather saw her name on the list and he decided he was going to go find her. So, he searched from relocation camp to relocation camp and eventually [did]. He used to say it was like finding a needle in a haystack. When he found her, he was determined to marry her. And within a year, they were married,” said Kantor.

They had a daughter born in a German relocation camp and emigrated to the United States a few years later. There, they made it a point to open their doors to those in need.

“It was an incredible love story. It’s an incredible story of righteous gentiles helping Jewish people, and it’s really defined for a lot of my family the kind of the trajectory of our lives,” explained Kantor. “For me, it’s less about religion and more about keeping up the customs and values that were so important to them that kept them going. That’s the driving force behind why, when there’s an opportunity locally for me to be able to help other people in this way, I do it. It’s an honor to their legacy.”

‘Critical needs to support resettlement agencies’

One of the Afghan refugees who moved to Kantor’s community told JNS he is appreciative of the help he received.

Krashow, whose last name is being withheld for safety reasons, worked for the Afghan Defense Ministry before fleeing the country during the Taliban’s takeover. His wife and two children remain in Afghanistan. He ended up in a camp on an army base in Fort Dix, N.J., before the Stamford Jewish community took him in.

“Jewish Family Services supported me, paid for medical treatment, rent, furnishings. They hired an attorney for me, helped me with my work permit,” said Krashow. “I never met a Jew in Afghanistan. I’m thankful for their support here.”

A year after the fall of Kabul, American Jewry is dealing with the Afghan refugee issue. Darcy Hirsh, managing director of public affairs for the Jewish Federations of North America, told JNS: “It’s an incredible testimony to the work of the Jewish community and our deep ties, to help those who are in need regardless of where they come from. A year later, there are still critical needs to support the resettlement agencies.”

The priority now for JFNA is to advocate for the passage of the Afghan Adjustment Act, which was introduced in Congress last month and appears to have bipartisan support.

It would provide a path to citizenship and permanent status for Afghans who were evacuated and admitted into the country on “humanitarian parole,” a temporary status that does not allow a path to legal permanent residency. There is worry that if the bill doesn’t pass in the current Congress, the humanitarian parole status will lapse.

“We’re very concerned that those individuals not permitted to stay here will have to go back to Afghanistan at severe risk to their lives,” said Hirsch. “We and other coalition partners, resettlement agencies and immigration groups are advocating for the Afghan Adjustment Act to be passed as soon as possible.”

(JNS.org)